This week, in the latest installment of the TENNIS.com Book Club, online editor Kamakshi Tandon and I are discussing “Break Point,” the 2006 tour diary by Vince Spadea with Dan Markowitz. Your comments are welcome as well.

Hi Kamakshi,

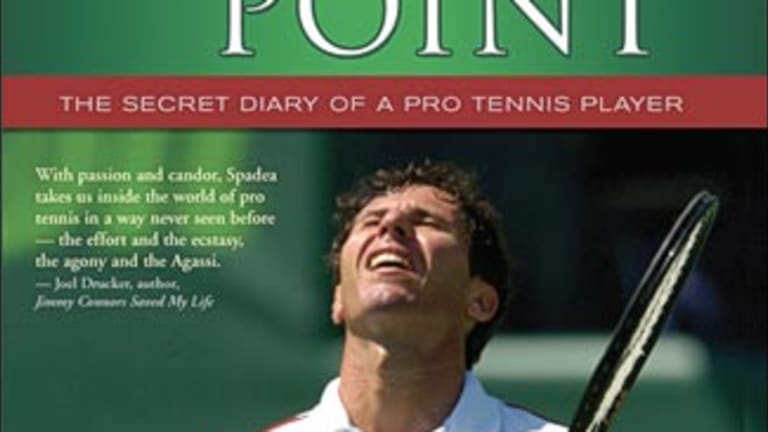

I enjoyed this book, more than I thought I would, but it's probably not one that’s going to impress a lot of people around you, particularly women in New York. I was standing on the subway reading it the other day. Two women were sitting in front of me; one of them saw the cover photo of a somewhat younger-looking Vince doing a double fist-clench, eyes closed, red face overwhelmed with emotion. She nudged her friend and they both looked at the cover and gave a snort of laughter.

I understood—the subtitle, “The Secret Diary of a Pro Tennis Player,” is kind of snort-worthy. But I wanted to tell them, “Hey this is a pretty good read. If, you know, you want to know what Tommy Haas and Jim Pierce are really like.” Actually, what I should have done was consult Vince’s handy in-book guide to picking up women, which he's named “Da Vince Code.” Sample advice: “Step 1: Appearance: Always keep a piece of gum in your mouth…. It can help you, if the girl rejects you, to continue to chew. It shows that you’re still confident and have everything under control. In extreme cases, you can just blow a bubble in her face and move on.” Damn, I could have used that with the girls on the subway!

Yes, Vince Spadea was 31 years old when his book, and his dating guide, were published. Which brings me straight to the question I’ve always had about him: Why, at an age when most tennis pros have left their youthful hair and hi-jinks behind, has Spadea begun to act out more? In recent years, he’s grown his hair, created an alter ego as a “tennis rapper,” and designed his own hip-hop-style clothing line. I’ve seen him a couple times in recent years rapping and cruising the grounds of a tournament with a buddy, in street clothes, his baseball cap turned sideways.

Is Spadea a case of delayed-adolescent attention seeking, or is he just a harmlessly colorful guy? Any decent autobiography should answer these questions and make you at least somewhat sympathetic to the writer. “Break Point” does both—while he’s hardly a saint or a white knight (see the bubble-blowing advice above), Spadea doesn’t come across as a jerk either. He’s observant, driven, honest, insecure, a loner who has never been part of the in-crowd on tour.

Spadea’s story is not unusual among tennis players and other athletes who dedicate their youths to their sports, growing up with social blinders on. The sport’s most famous example of this was Bjorn Borg, the single-minded Swede who said good-bye to the tennis tour at 25, left his longtime coach and his practice regimen behind, and quickly made up for lost time on the international party tour.

At the same age, Spadea also made a break. He finally stopped traveling with his family, and his dad stopped working as his coach for the first time. Spadea’s father, Vince, Sr., is a sort of Italian-American—and somewhat gentler—version of Mike Agassi. He taught himself the game so he could teach his kids to play, and then dedicated his life to their tennis. Like Andre, Vince’s older sister Luanne was a national junior champion, and Vince clearly ate, slept, and drank the sport through his teens. With his father off the sidelines, Spadea must have felt the freedom to put more of his personality on display.

Vince Sr., is certainly a character—and not easy to get away from. I’ve met him a couple times, as anyone who’s spent time around tennis has. At the 2004 French Open, we had a long conversation (though we didn't know each other) about everything going on during the clay-court season, about Vince and every other player imaginable. Vince Sr., is a nice guy, and a font of tennis info—I learned, for example, that the Chileans have struggled at the French Open in the past because they put so much effort into the World Team Cup that’s played a week before. It’s a big, televised event in Chile, apparently. Who knew?

But while Borg bagged the sport, Spadea seems to have redoubled his tennis efforts even as he’s brought out new aspects of his personality. He’s spent the years since he split with his father searching in the wilderness for a coach—he even worked with Pete Fischer for a decent amount of time (Fischer helped him in a lot of ways, but eventually lost faith in Spadea’s ability to improve). Beneath his antics, Vince remains dedicated to the “battle.” If the book gets one thing across, it’s how much effort and will it takes to do what he does, and how it's almost a full-time job finding ways to stay motivated. Spadea never seems to tire of the challenge, though, and I came away admiring how his tenacity has only increased with age—a rarity in any line of work.

OK, that’s it for now. More on the book's “scandalous” behind-the-scenes stories, and Vince's (insightful) descriptions of Agassi, Sampras, Blake, Roddick, etc., later.

Were you surprised by his print personality, Kamakshi?

Steve