by Pete Bodo

We're on the cusp of the Davis Cup championship round, and all eyes will be on Rafael Nadal, who's been compared to a bull, usually in an unimaginative way based on his straight-ahead game, his obvious strength and stamina, and our penchant for culturally-based cliche (Bjorn Borg, after all, was the "Viking God" even though his first name is Swedish for "bear" and his pulse rate of around 60 was closer to that of Ursus Horribilis than, say, Leif Ericson or Anni-frid Lyngstad of ABBA).

Way back when, I compared Nadal to Ferdinand the Bull because, for all his strength, Nadal seemed to have a genuinely gentle nature (if you're too young to remember Ferdinand, just click here and check out the YouTube clip). I see that now Rafa is often called the "humble bull" (at least in these parts). I guess that six straight losses to Novak Djokovic can humanize you in that way. But I'm glad to see that we're closer now to my original Ferdinand analogy, which always was meant affectionately.

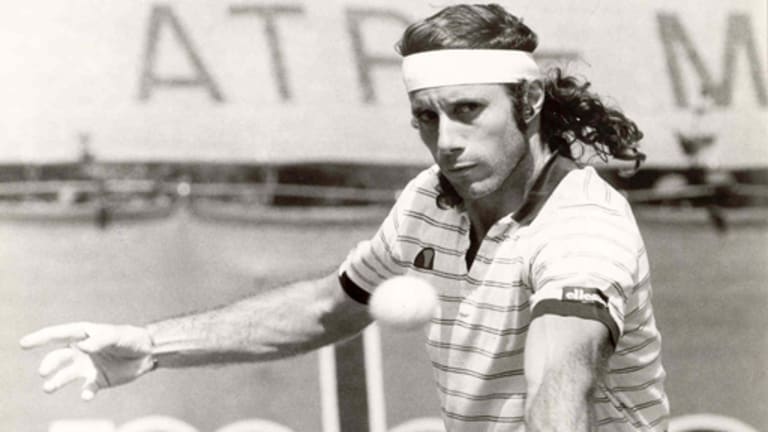

Anyway, given the occasion (Spain v. Argentina), and the fact that Argentina appears to have its work cut out, I want to focus on the man who was the original "bull" of the Open era, Argentina's Guillermo Vilas. I wrote about him extensively in, among other places, my Celebrating Willy post some years ago, and his name has cropped up quite a bit over the past 12 months, when winning streaks and "greatest season, ever!" were hot topics.

Vilas looked even more solid than Nadal although he lacked the raw, explosive quality of Nadal. "Just" 5'11", Vilas was built like a Coke machine, and he made stamina, tenacity, and an appetite for suffering (through mind-boggingly long practice sessions under the tutelage of Ion Tiriac and competitive matches) his trademarks. Those bullish qualities paid off over a career that spanned 19 years of Grand Slam play and saw Vilas play in over 100 finals (his record in finals: 62-42).

But for all his accomplishments, the most striking aspect of Vilas's resume is that the original bull never officially held the No. 1 ranking. He maxed out on the computer at No. 2, although back in those days some of the more subjective year-end rankings still carried significant weight. I voted for Vilas as the No. 1 player for 1977, and I believe that's where he ended up in our Tennis magazine rankings (at the time, those were highly regarded honors). And if memory serves, our rival, long defunct World Tennis magazine, gave the top sport to Borg because the one thing everyone, including the rankings panel of Tennis magazine, knew is that Borg owned Vilas — when they met. The career head-to-head was 17-5 for Borg, which goes a long way to explaining how Vilas never ended up the official year-end No. 1.

Anyway, 1977 was Vilas' best year — even if it was one during which Borg was injured. Vilas won two majors, the French Open (d. Gottfried, losing a grand total of three games in three sets) and U.S. Open (d. Connors) and 16 of the 31 ATP events he entered. His overall W-L record was a mind-boggling 145-15 (130-15 in ATP play). Vilas won seven consecutive tournaments (beginning with his first event after Wimbledon, Kitzbuhel) and 72 of his final 73 matches of the year leading up to the Grand Prix Masters (now the World Tour Finals). That stretch included the 46-match winning streak that Djokovic recently threatened but failed to surpass.

Some year. It just goes to show that it's not just about winning percentages, because Vilas' 1977 doesn't even make the top 10 in that category.

But Vilas was also one of the all-time great Davis Cup competitors. His overall record is 57-24 (an outstanding 45-10 in singles (a winning percentage of .818), and 12-14 in doubles, which he usually was obliged to play for lack of depth on the Argentina side). By way of comparison, Vilas' domestic rival Jose Luis Clerc, who ranked as high as No. 4 in the world at one time, was a combined 31-24. And David Nalbandian, a Davis Cup hero at home and the veteran of the squad that will face Spain starting today, is presently 33-10 (a sterling 22-5 in singles, which is almost an identical winning percentage to that of Vilas, but in almost exactly half as many matches, 55-27).

In other words, Nalbandian might have required a career twice as long to match Vilas' output, although the team element in Davis Cup is a factor that can skew the individual record. If you're wondering how Vilas and Nalbandian stack up against Nadal and Spain, here you go:

Manuel Santana is the undisputed workhorse of the Spanish Davis Cup squad; he played a stupefying 120 matches and had an outstanding 69-17 record in singles, for a winning percentage of .800 — slightly below that of Vilas. Nadal is presently 20-5, and a brilliant 18-1 in singles. And let's face it, folks, not all of those matches were on red clay.

I'm not sure anyone can match that .947 winning percentage of Nadal's, which is bad news for Argentina today. Just as Guillermo Vilas must be the best player never to hold the official No. 1 ranking, so his countrymen in Argentina seem fated, at least for now, to remain the best team never to win the Davis Cup because of Nadal.