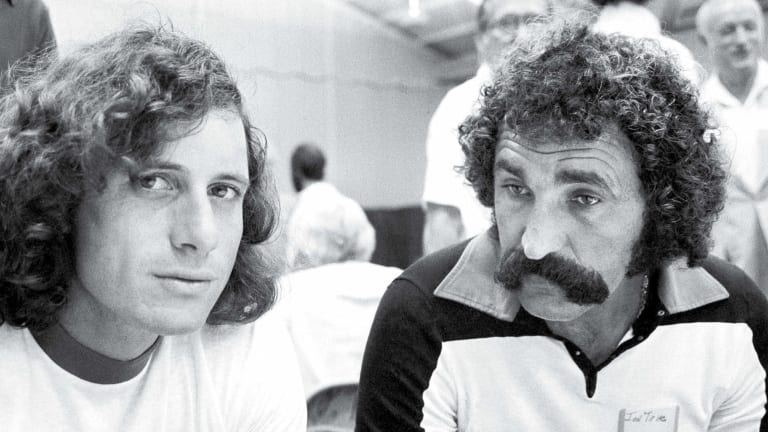

It’s the face. When they talk about Ion Tiriac, they always talk about the face. He first entered tennis at the dawn of the Open Era, a Romanian former ice hockey player blowing into the sport like a searing, malevolent wind out of the mysterious and threatening Communist east.

The Face of Ion Tiriac

By May 03, 2016Pick of the Day

Madrid Open Betting Preview: Joao Fonseca vs. Tommy Paul

By Apr 25, 2025Lifestyle

Iga Swiatek shares first look at new Lancôme campaign

By Apr 25, 2025Pick of the Day

Madrid Open Betting Preview: Mariano Navone vs. Ben Shelton

By Apr 25, 2025pickleball

Andre Agassi to make pro pickleball debut with Anna Leigh Waters at US Open Pickleball Championships

By Apr 24, 2025Tennis.com Interview

Never judge, just love: Jessica Pegula and her dogs have been a winning pair

By Apr 24, 2025The Business of Tennis

Madrid Open unveils expansion plans that impress Carlos Alcaraz and Coco Gauff

By Apr 24, 2025Social

"Done with my crashout": Naomi Osaka ready for reset after losing Madrid opener

By Apr 24, 2025Pick of the Day

Madrid Open Betting Preview: Borna Coric vs. Matteo Arnaldi

By Apr 24, 2025Style Points

FIRST LOOK: Coco Gauff to debut new Miu Miu x New Balance tennis collection in Rome

By Apr 23, 2025The Face of Ion Tiriac

After 50 years, Ion Tiriac is still making things happen.

Published May 03, 2016

The Face of Ion Tiriac

Advertising

Advertising

The Face of Ion Tiriac