News

Net play: revisiting the volley

By Jun 15, 2021News

Adrian Mannarino headbutts racquet butt cap and draws blood, recalling Mikhail Youzhny

By Jan 03, 2024News

22-year-old Iga Swiatek to surpass 20 million dollars in career prize money

By Aug 28, 2023News

20-year-old Carlos Alcaraz surpasses 20 million dollars in career prize money

By Aug 21, 2023News

The ITF's Katrina Adams stays on the front lines for women with the Tory Burch Foundation Sports Fellowship

By May 02, 2023News

Daniil Medvedev, Stefanos Tsitsipas hit major career prize money milestones after Monte Carlo

By Apr 17, 2023News

Petra Kvitova on that tie-break against Rybakina: “I think it was the longest one I ever played in my life”

By Apr 02, 2023News

Barbora Krejcikova surpasses $10 million in career prize money after Indian Wells

By Mar 20, 2023News

Carlos Alcaraz gives shelter to ballkid as rain starts pouring in Rio

By Feb 22, 2023News

Gabriela Sabatini among packed crowd in Buenos Aires to watch Carlos Alcaraz’s comeback match

By Feb 16, 2023Net play: revisiting the volley

Sadly, the refinement and deployment of the volley is greatly neglected.

Published Jun 15, 2021

Advertising

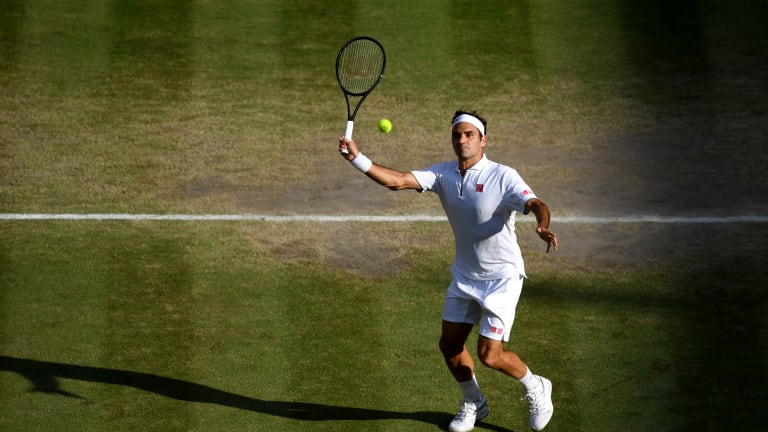

Federer hits a high forehand volley: Getty Photos

© Getty Images

Swift movement and sharp volleys carried Edberg to six Grand Slam singles titles.

© Getty Images

Advertising

Just a few years ago, a decade after her career had ended, Navratilova admitted she was having fun experimenting with swing volleys, like the player. (Getty Images)