Tennis players of a certain age might remember hearing tall tales about the practice habits of legendary grinders like Bjorn Borg and Mary Joe Fernandez. “I heard Borg spends one week hitting crosscourt, and the next week hitting down the line,” or “Mary Joe has to make a thousand shots in a row before she can go home.” The message was: To practice like a pro, you need to hit a ton of balls; to become a pro, you can’t miss any.

Forty years later, that message hasn’t evolved much. When it comes to practice, the focus is still on repetition. And that makes sense for players who are developing their strokes—there’s no substitute for muscle memory. But the game has changed since the days of Borg and Fernandez, and our knowledge of how to win matches has deepened. It’s time our practice habits caught up.

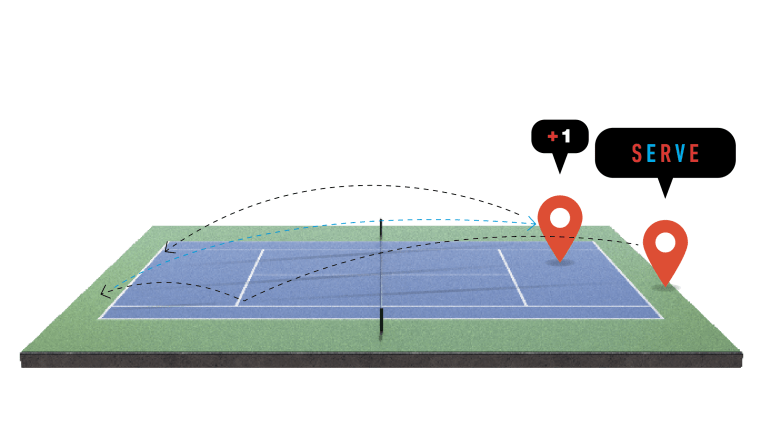

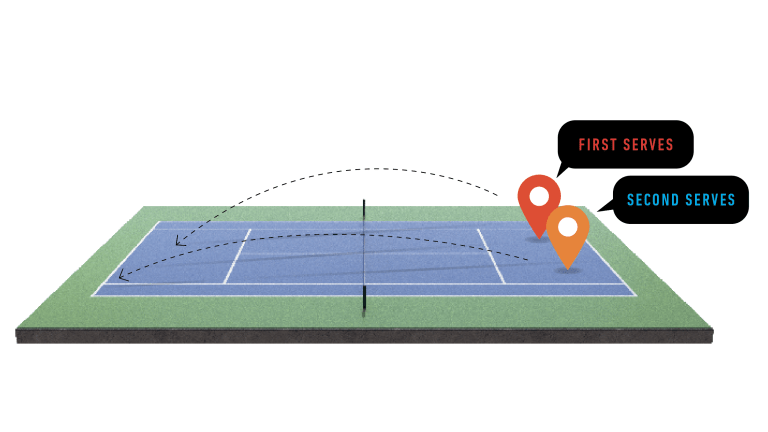

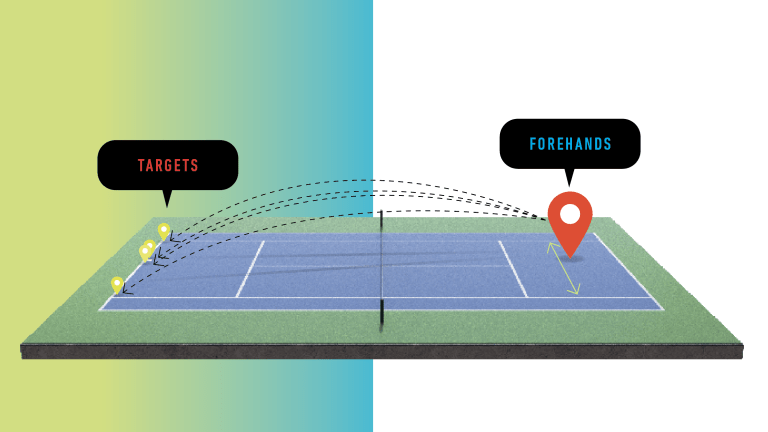

Big-time tennis today is about the “serve-plus-one,” about the first strike, about dictating play with the forehand, about forcing your opponent into errors. We know 70 percent of rallies are over in four shots or less, so why are we practicing as if we need to win a 100-ball marathon on every point? We know the serve and return are the most important shots, so why aren’t we working on them more? We know the pros are using analytics and sports psychologists to get an edge—can we follow their lead?

With those questions in mind, we’ve consulted with two coaches who are at the leading edge of tennis training. Craig O’Shannessy has been an analytics-based adviser for dozens of pros, including Novak Djokovic. Jeff Greenwald is a sports-psychology consultant and author of The Best Tennis of Your Life: 50 Mental Strategies for Fearless Performance.

Together, at the Brain Game Tennis website, they’ve put together a course that helps players use analytics and sports psychology during matches. Here, they walk us through a step-by-step plan that will integrate those disciplines into our training regimens—and bring our practice routines into the modern era.