#CentreCourtCentennial

1922: Suzanne Lenglen strikes a blow for tennis democracy, then christens the “House that Suzanne Built” in the fastest Wimbledon final ever

By Jun 14, 2022#CentreCourtCentennial

Serena Williams' energetic return to Centre Court after a year away from the game was a brave effort, and one worthy of her legend

By Jun 29, 2022#CentreCourtCentennial

2009: The first full match under Centre Court's roof showcased British tennis' newest Wimbledon title contender, Andy Murray

By Jun 23, 2022#CentreCourtCentennial

2008: Rafael Nadal and Roger Federer produced a quantum leap in quality and entertainment in their classic, daylong final

By Jun 22, 2022#CentreCourtCentennial

2007: After fighting for pay equity at Wimbledon, Venus Williams became the first woman to collect an equal-sized champion’s check

By Jun 21, 2022#CentreCourtCentennial

1980: The five-set final between Bjorn Borg and John McEnroe was the pinnacle of their rivalry—and the Woodstock of their tennis era

By Jun 20, 2022#CentreCourtCentennial

1975: In defeating a seemingly invincible Jimmy Connors, Arthur Ashe showed that with enough thought and courage, anyone in tennis can be beaten

By Jun 19, 2022#CentreCourtCentennial

1968: At the first open Wimbledon, Billie Jean King receives her first winner’s check—and notices a “big difference” with her male counterparts

By Jun 18, 2022#CentreCourtCentennial

1967: With the Wimbledon Pro event, professional tennis finally comes to the amateur game’s most hallowed lawn

By Jun 17, 2022#CentreCourtCentennial

1957: “At last! At last!” Althea Gibson fulfilled her destiny at Wimbledon, and with every win she opened up the sport a little wider

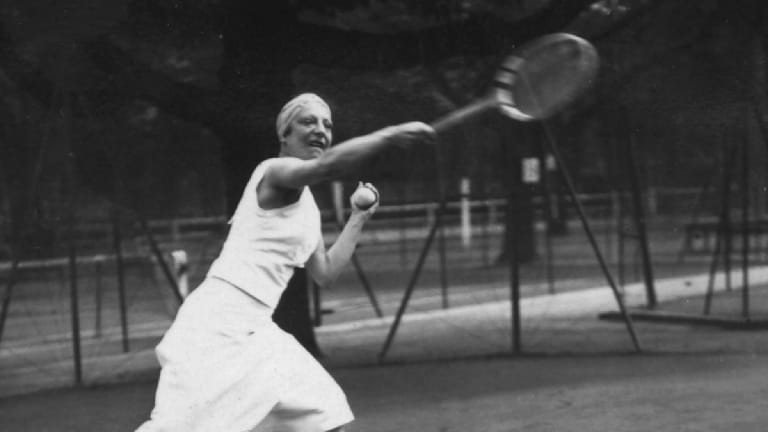

By Jun 16, 20221922: Suzanne Lenglen strikes a blow for tennis democracy, then christens the “House that Suzanne Built” in the fastest Wimbledon final ever

The balletic 23-year-old was as responsible as anyone for the All England Club’s move from its original SW19 location on Worple Road to more spacious grounds on Church Road.

Published Jun 14, 2022

Advertising

Suzanne Lenglen, in 1920.

© AFP/Getty Images

Advertising

Suzanne Lenglen would go 332-7 for her career, win 179 straight matches at one point, and take home 45 titles in a single season.

© Tennis Channel