This year marks the 50th anniversary of TENNIS Magazine's founding in 1965. To commemorate the occasion, we'll look back each Thursday at one of the 50 moments that have defined the last half-century in our sport.

“It’s eerie what the tiebreakers do,” Arthur Ashe said at the 1970 U.S. Open. “Those red flags are out and the crowd is absolutely silent.”

Once upon a time, in that briefly freewheeling era of tennis known as the early ‘70s, scarlet banners were periodically furled and unfurled across the lawns at Forest Hills. As Ashe said, whenever one went up, the tension around the court escalated with it. When they saw one, fans knew that a set had reached 6-all, and it was time for Sudden Death.

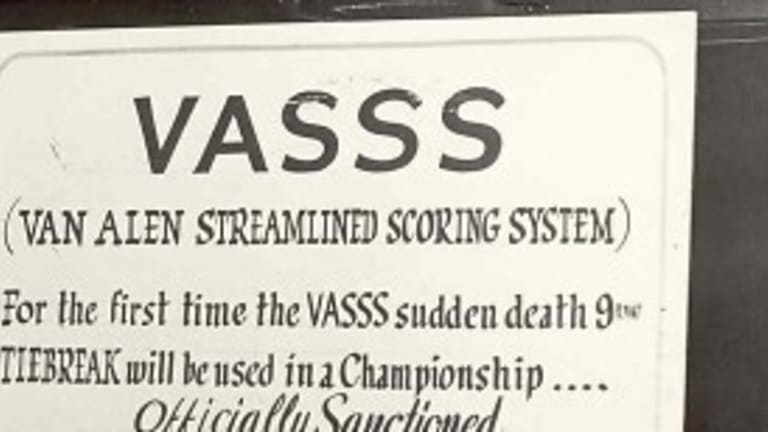

In case anyone didn’t get the idea, the banners came with the letters S and D emblazoned across them in white. In between, in smaller type, was a logo that consisted of a V crossed with an A. Those letters were harder to make out, but they were every bit as significant. They stood for Van Alen. Jimmy Van Alen, to be precise, the man who had labored for close to two decades to make his dream of Sudden Death—or what we now refer to, in these rhetorically safer times, as the tiebreaker—a reality.

The color of the flags was appropriate, because the tiebreaker represented one of the first and only true revolutions in tennis history. Known as the “Newport Bolshevik,” Van Alen was, as the term suggests, an unlikely rebel. The son of Daisy Astor Van Alen Brughiere, he grew up in a Newport mansion with servants in the kitchen, suits of armor standing guard in the foyer, and a Rolls-Royce parked in the driveway. But it was precisely his high standing within the amateur tennis establishment that gave this “paunchy character in burgundy suede shoes and a matching complexion,” as Bud Collins described him, a chance to change the game so radically from within.

Van Alen spent his youth playing tennis on the grass courts and waltzing on the verandah at the Newport Casino, a Gilded Age country club designed by Stanford White. As an adult he naturally assumed tournament-director duties at the amateur event known as the Men’s Invitational, which was staged there each summer.

In 1954, the two finalists at Newport, Ham Richardson and Straight Clark, made Van Alen rue the day he had invited them to his beloved Casino. On the afternoon of their match, the most highly anticipated event wasn’t the singles; it was the doubles final that was supposed to follow, and which featured two Aussie up-and-comers named Lew Hoad and Ken Rosewall. While the crowd waited impatiently, Richardson and Clark engaged in a war of serving attrition that finally ended with a 6-3, 9-7, 12-14, 6-8, 10-8 Richardson victory. As they were plodding toward their conclusion, Van Alen, whose face had gone from burgundy to purple, was forced to switch Hoad and Rosewall to an outside court, where most of the crowd stood to watch. The Newport Bolshevik had seen enough.

“It struck me,” Van Alen said, “that there had to be a better, more exciting way to control the length of matches without those damnable deuce sets. Matches like that are Chinese water torture for players, court officials, and fans alike.”