This year marks the 50th anniversary of TENNIS Magazine's founding in 1965. To commemorate the occasion, we'll look back each Thursday at one of the 50 moments that have defined the last half-century in our sport.

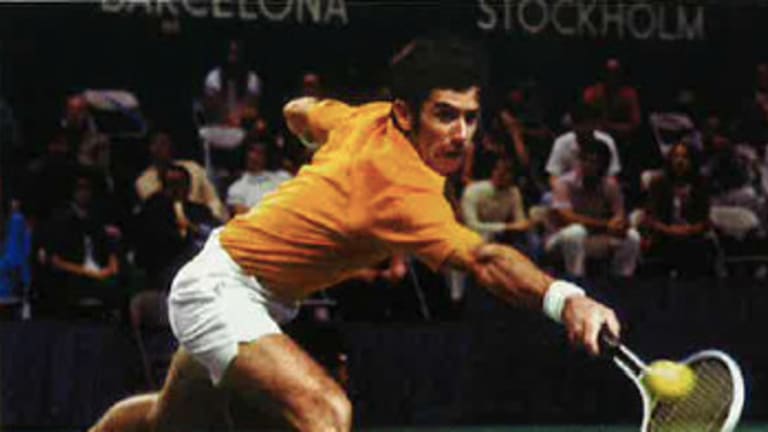

1972: The Rod Laver vs. Ken Rosewall WCT Final in Dallas

By Mar 12, 2015ATP Munich, Germany

Ben Shelton uses altitude to his advantage, joins Alexander Zverev in Munich quarterfinals

By Apr 16, 2025WTA Stuttgart, Germany

Iga Swiatek in Stuttgart: From clay court to carpool karaoke!

By Apr 16, 2025Lifestyle

Thorne taps Ben Shelton to launch new on-the-go performance line

By Apr 16, 2025Social

Lois Boisson had the perfect response to Harriet Dart deodorant controversy

By Apr 16, 2025Social

Dominic Thiem ‘loves’ watching Jakub Mensik and Joao Fonseca

By Apr 16, 2025ATP Munich, Germany

Ben Shelton: European football's newest superfan? Lefty making most of Munich debut

By Apr 15, 2025ATP Barcelona, Spain

Casper Ruud, Stefanos Tsitsipas open Barcelona bids in quest to halt further ranking slides

By Apr 15, 2025Tennis.com Interview

Jan-Lennard Struff sees Munich title defense bid as 'perfect opportunity' to turn 2025 around

By Apr 14, 2025Stat of the Day

Andrey Rublev storms to 100th ATP 500 win of career with opening victory in Barcelona

By Apr 14, 20251972: The Rod Laver vs. Ken Rosewall WCT Final in Dallas

Looking back at the match that made tennis in America.

Published Mar 12, 2015

Advertising

Advertising

1972: The Rod Laver vs. Ken Rosewall WCT Final in Dallas

Advertising

1972: The Rod Laver vs. Ken Rosewall WCT Final in Dallas