For our sixth annual Heroes Issue, we’ve selected passages from the last 50 years of Tennis Magazine and TENNIS.com—starting in 1969 and ending in 2018—to highlight 50 worthy heroes. Each passage acknowledges the person as they were then; each subsequent story catches up with the person, or highlights their impact, as they are now. It is best summed up with a quote from the great Arthur Ashe, that was featured on the cover of the November/December issue of this magazine in 2015: “True heroism is remarkably sober, very undramatic. It is not the urge to surpass all others at whatever cost, but the urge to serve others at whatever cost.”

U.S. Champions—Women’s Singles: 1957 Althea Gibson; 1958 Althea Gibson - Tennis Magazine / February 1982

“Are you interested?” Dr. Robert Johnson asked the 18-year-old girl.

“Who wouldn’t be interested in a deal like that?” she shot back.

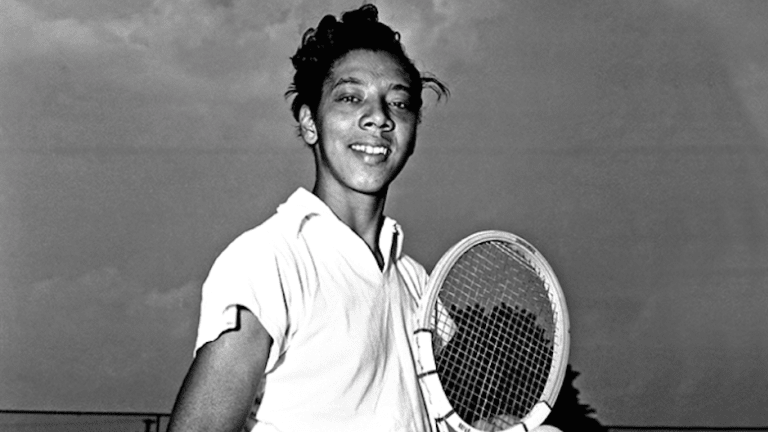

The girl was Althea Gibson, a long, lanky, confident kid from Harlem who liked roaming the streets of New York more than she liked going to school. What she liked most was winning tennis matches, and she had come to Ohio to do that at a tournament held by the American Tennis Association (ATA), which in the segregated days of 1946 was the nation’s haven for African-American players. Gibson reached the final, and along the way caught the eyes of Johnson and Hubert Eaton, two doctors and tennis lovers from the South. They offered her a “deal” she couldn’t refuse: a chance to live, train and travel to tournaments with them.

If there was an eye you wanted to to catch in the ATA, it was Johnson’s. A former college football star nicknamed “Whirlwind,” he founded the organization’s Junior Development Program, and pioneered the concept of the tennis academy on his backyard court in Lynchburg, VA. It was there that Johnson hoped to train a black player who could do what Jackie Robinson was doing for baseball: Break down the country’s color barrier in tennis.

Johnson believed he would need someone who was not only highly skilled, but whose manners were above reproach. He didn’t want a white tournament official to be able to point to the behavior of one of his kids and say, “See, this is why we don’t let them in.”