NEW YORK—Watching Lleyton Hewitt fight his way right through to the bitter end of his four-set defeat to David Ferrer this afternoon, I couldn’t help but think of the Black Knight in Monty Python and the Holy Grail, the one who has all four of his limbs hacked off by King Arthur but insists that “it’s just a flesh wound,” and taunts Arthur to continue fighting.

I should say that he reminds me of the Black Knight in all ways but one: Nobody was laughing at Lleyton Hewitt.

Though the Australian ultimately lost the last seven games of the match for a final score of 7-6 (9), 4-6, 6-3, 6-0, he continued to scrape and claw, to try drop shots and net approaches and gassed up groundstrokes and anything else he could think of to stem the tide of adversity, even as it overwhelmed him and washed him out to sea.

Who could fault his optimism? Few players have had their tenacity rewarded more than Hewitt, who’s done everything from survive a two-set deficit to Roger Federer (in the 2003 Davis Cup semifinals) to defeat then-reigning clay court king Gustavo Kuerten on clay in Brazil (also in Davis Cup, in 2001) to gutting out any number of matches large and small, against players great and unheralded, over the past decade and a half.

At 31, Hewitt is only a year older than his stylistic soulmate Ferrer, but the two might as well be from different generations. The Aussie had his greatest successes in the early 2000s, winning the U.S. Open and Wimbledon and twice finishing the year at No. 1, while Ferrer’s breakthroughs came later, this being his best year so far on tour. Ranked No. 5, he’s won five titles in 2012 (second only to Federer) and reached the quarterfinals of the Australian Open, the semifinals of the French Open, and the quarterfinals at Wimbledon. Thanks to Rafael Nadal’s withdrawal, he entered this year’s Open the No. 4 seed, whereas Hewitt, currently ranked No. 125 and besieged by injuries in recent years and having undergone recent foot surgery, needed a well-deserved wild card to get in.

Because they peaked at different times in their playing lives, Ferrer currently holds the baton that was passed from Chang to Hewitt to him, that of the dogged, never-say-die retriever, the tenacious baseliner who makes up for deficiencies of stature and power with surfeits of will and grit. The difference, of course, is that Chang and Hewitt were able to win Slams where Ferrer has not.

In tennis, as in life, timing is everything: Hewitt, who bagged his first ATP tour title at Adelaide, Australia, at the age of 16, announced himself as a prodigy and enjoyed early success. Fully developed during the waning days of Sampras and Agassi, he—along with Andy Roddick—was able to sneak in some major-title success before the Federer-Nadal-Djokovic era that has kept any other player, with the one exception of Juan Martin del Potro in 2009, from winning a Slam since January 2005. Just consider this year, in which Ferrer’s Slam runs have ended at the hands of Novak Djokovic (Australia), Nadal (Roland Garros), and the title-less but perennial Slam contender Andy Murray (Wimbledon).

Of course, nobody could have known what a dominant quartet was hovering in the distance in the early 2000s, but as it’s turned out, fate has been a little cruel to Ferrer. For all his consistency and tenacity, it’s tough to imagine a man of his limited physical attributes winning a Slam because, to put it bluntly, he doesn’t have the game to bother the tour leaders. Other members of the Top 10 such as del Potro, Tomas Berdych, and Jo-Wilfried Tsonga may be ranked below Ferrer, but with their more imposing physiques and bigger games, have a greater chance of winning a major. Indeed, all of those players have been to a Grand Slam final, which Ferrer, so far, has not.

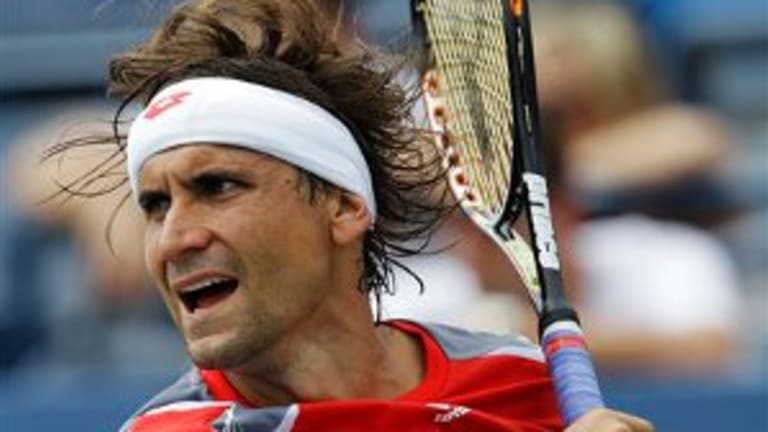

The pleasures and limitations of Ferrer’s and Hewitt’s games were laid out for all to see in their third-round match on Louis Armstrong Stadium this afternoon. Although Hewitt was coming off a come-from-behind, five-set win over Gilles Muller, he seemed fully recovered at the outset: The first set was a one-hour, 14-minute barnburner in which the players ran each other side to side for great stretches, traded breaks, and then played a 20-point tiebreaker in which Hewitt held five set points but failed to convert any of them, and ultimately handed the set to Ferrer with a failed drop-shot attempt. For a great many 31-year old players, losing that would have been the death blow, but another grueling comeback seemed possible when Hewitt broke in the second set, then ran it out at 6-4.

Ferrer turned up the heat after that, taking greater initiative with his forehand and seizing control of more and more points. Thought Hewitt didn’t admit exhaustion in his press conference, as time went on, he certainly appeared to be hemorrhaging energy while Ferrer seemed to gain it. When the match was over, Ferrer threw his arms up in victory, a huge smile plastered on his face. It hadn’t been easy.

Watching these two dogged combatants duke it out for three-and-a-quarter hours, I couldn’t help but wonder at how they must define success: Just as one might wonder why Hewitt continues to compete when his title days are surely behind him, it’s tempting to ponder why Ferrer goes to the trouble of pushing himself, major after major—he hasn’t missed one since the 2003 Australian Open—when, at the end of the day, the ultimate success will likely remain just out of reach. He emerged triumphant today, but should he make it to the semifinal and find Djokovic waiting for him, it’s difficult to imagine a different outcome from the straight-sets disappointment he was handed by the Serb in the same round here in 2007.

But never mind all of that. Both Ferrer and Hewitt show us the value of living for the moment, as both competitor and fan. They prove that triumphs don’t have to be punctuated by trophies, that there’s plenty of nobility in a hard-fought win—and even in a four-set loss. In a year’s time, nobody will remember Hewitt’s taking out Muller in the second round, and they likely won’t remember Ferrer’s win over a past-his-prime Hewitt on his way to whichever round he bows out in, either. But those of us who were present today will remember not just Ferrer’s win, but also the fight that Hewitt brought to the match, and the tournament—not just against his opponents, but seemingly against the ravages of time itself.

During the final two sets of Ferrer-Hewitt today, the sounds of the crowd cheering for Andy Roddick wafted in from Arthur Ashe Stadium. Roddick, of course, has announced that this tournament will be his last, his stated reason for retirement being that he doesn’t simply want “to exist” on the tour and that his body won’t permit him to compete at the highest level anymore. Recent titles in Eastbourne and Atlanta aren’t enough; Roddick perceives himself as a Grand Slam champion, and professional life without that possibility isn’t worth living for him. Hewitt, who grew up loving <em>Rocky</em> movies, sees himself as a fighter, ready to take on anyone, anytime, whether it’s an unsung opponent on an outer court or Spanish soulmate on one of the tennis’ biggest stages.

For as long as he keeps swinging away, we’ll keep watching.