For a few summer months in the early 2000s, the Knickerbocker Field Club was a mythical place to me. Literally. I knew the address, I knew someone who played there, I had even read about its century-long history online. But I couldn’t find it.

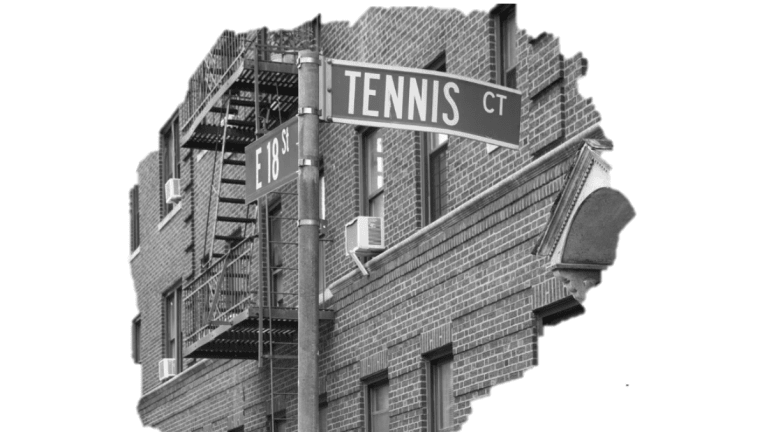

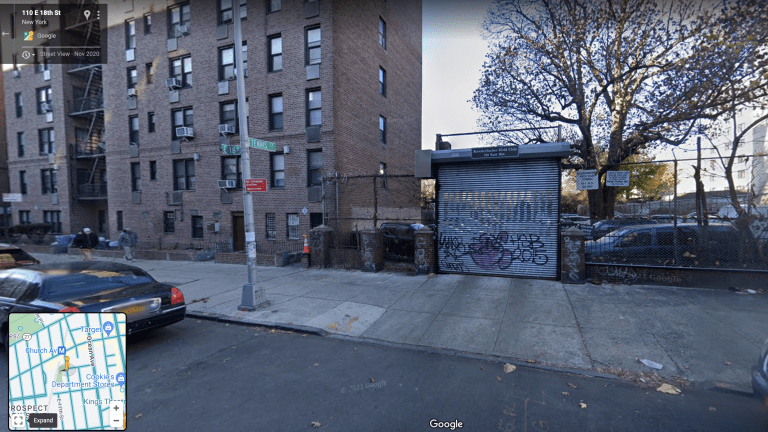

This wasn’t unusual. The first person who alerted me to the club’s existence said, “Most people don’t even know it’s there.” He lived in my building in Brooklyn, and had seen me walking toward the nearest public park with a racquet bag in tow. He mentioned that he played at “The Knick,” a collection of five clay courts wedged between a subway line and a set of apartment buildings, on a street called Tennis Court, in Flatbush, a neighborhood not known for its wide-open spaces. “The courts are the best in Brooklyn.”

It all sounded a little too good to be true, and for a while I started to think it was. I rode my bike to the address on Tennis Court…and found a gravel parking lot. I rode there a week later, walked into the lot, wondered if I was trespassing, and walked back out. Finally, on a third trip later that summer, I dared to go all the way in and turn left. There they were, those five clay courts, all of them occupied on a sunny Saturday morning.