International Tennis Hall Of Fame

A time travel odyssey: Fifty years as a tennis historian

By Jul 14, 2022International Tennis Hall Of Fame

International Tennis Hall of Fame launches “Be Legendary” youth program in Melbourne, Indian Wells and Miami

By Dec 05, 2024International Tennis Hall Of Fame

Maria Sharapova and the Bryan brothers are elected to the International Tennis Hall of Fame

By Oct 24, 2024International Tennis Hall Of Fame

Maria Sharapova’s election to the Hall of Fame may be polarizing, but it’s deserved

By Oct 24, 2024International Tennis Hall Of Fame

Maria Sharapova, Bob and Mike Bryan nominated for International Tennis Hall of Fame

By Sep 03, 2024International Tennis Hall Of Fame

Leander Paes: Doubles maestro, International Tennis Hall of Fame inductee

By Jul 19, 2024International Tennis Hall Of Fame

Richard Evans, veteran journalist, joins International Tennis Hall of Fame Class of 2024

By Jul 18, 2024International Tennis Hall Of Fame

Vijay Amritraj, 2024 International Tennis Hall of Fame inductee, is making tennis communal

By Jul 17, 2024International Tennis Hall Of Fame

New in 2025: Tennis Hall of Fame moves ceremony to August, Newport to host combined 125-level event in July

By Jul 17, 2024International Tennis Hall Of Fame

Leander Paes and Vijay Amritraj are the first Asian men elected to the Tennis Hall of Fame

By Dec 13, 2023International Tennis Hall Of Fame

A time travel odyssey: Fifty years as a tennis historian

It’s a joy to commune so much with our sport’s rich history; back and forth, forward and back, again and again and again.

Published Jul 14, 2022

Advertising

Advertising

Helen Willis Moody was an all-timer, but in the 1926 "Match of the Century," she "met a baptism of fire which was strange and new to her," wrote James Thurber.

© AFP via Getty Images

Advertising

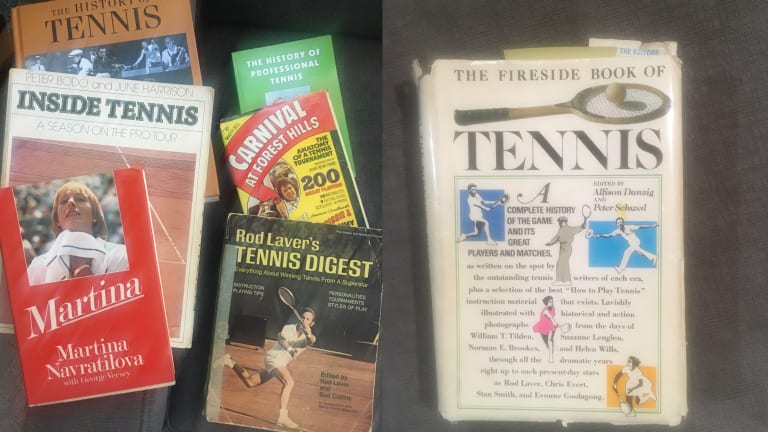

Some of the author's many tennis books of reference.