“The best thing is watching the players get out on the court and smile while they’re warming up,” Bill Massie says. “They look down, and it’s like they can’t believe the surface they’re playing on.”

What is this magical material that has the power to bring delight even to nervous young tennis players preparing to compete? It’s the sport’s original surface, but one that few of us ever have the chance to trod today: grass. Specifically, perennial rye grass, the type that has been grown and used at Wimbledon since 2001.

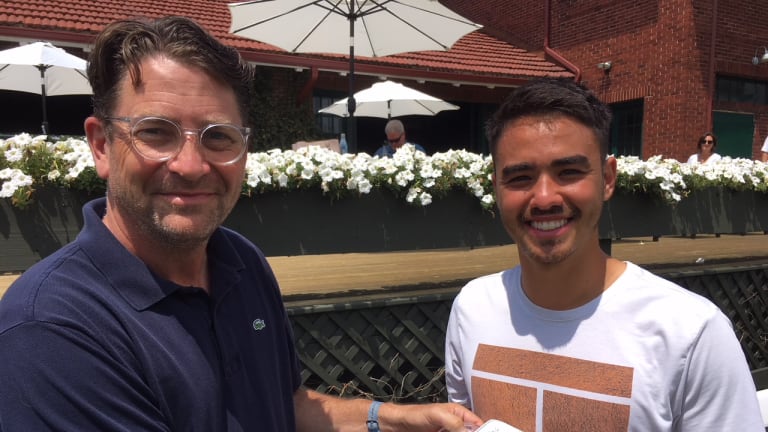

For the last four years, it has also been the type that Massie has grown on the 24 grass courts at the Wessen Lawn Tennis Club in Pontiac, Michigan, 25 miles northwest of Detroit. Lawn tennis, on 24 perennial rye courts, in a hardscrabble assembly-line town in Michigan? Is this real life? The unlikely idea was all Massie’s.