It’s been more than 35 years since Ronald Reagan stated, during his first inaugural address, “Those who say that we’re in a time when there are no heroes, they just don’t know where to look.” We discovered heroes in every state, starting with the determined 69-year-old who won a match at an ITF Pro Circuit event earlier this year in the Alabama town of Pelham, and culminating with the coach who has overcome multiple sclerosis to build a winning program at the University of Wyoming. Their compelling stories of courage, perseverance and achievement demonstrate that the message delivered by our 40th President rings as true today as it did then.

"The problem of the 20th century," the African-American scholar W.E.B. DuBois wrote in 1903, "is the problem of the color line." DuBois' prediction was more than prescient. We're well into the 21st century, and as anyone who follows the news today understands, that line is still very much with us. But what he couldn't have realized was how much the seemingly innocuous realm of sports would do to make the line just a little harder to see.

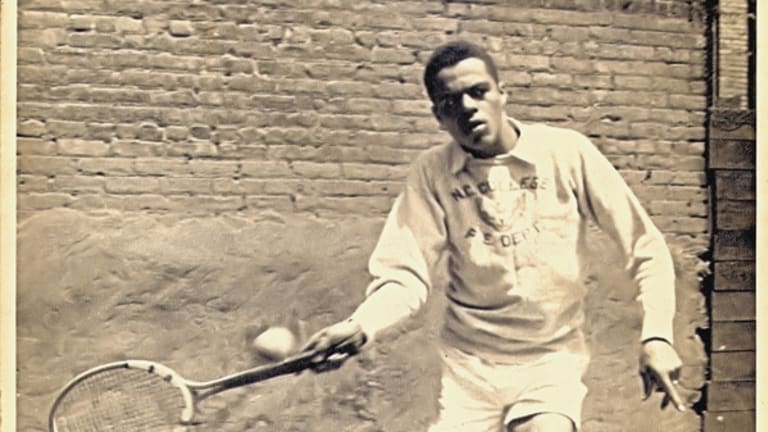

Every American learns the story of how Jackie Robinson integrated Major League Baseball in 1947. Many tennis fans are aware that Althea Gibson shattered barriers at the U.S. Nationals at Forest Hills in 1950. But far fewer know that seven years before Robinson’s breakthrough, a decade before Gibson’s and 14 years before Brown v. Board of Education made school segregation illegal, black and white met across a net in the first high-level interracial tennis match, and one of the few interracial sporting events of any kind during that era of “separate but equal.”

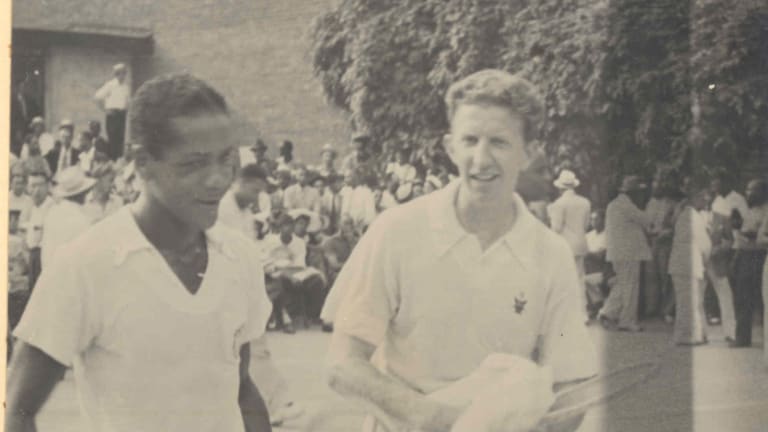

On July 29, 1940, a crowd of more than 2,000 filled the bleachers at the Cosmopolitan Tennis Club to capacity. The best white player in the United States, Don Budge, traveled to Harlem to face the best black player, Jimmy McDaniel, in an exhibition staged by Budge’s racquet company, Wilson Sporting Goods. According to tennis journalist Doug Smith, those who couldn’t get in “watched from fire escapes and from windows in surrounding buildings. Those unable to see listened to the score, which was announced on a public address system.” This was, as Smith wrote, a major event in the black community.

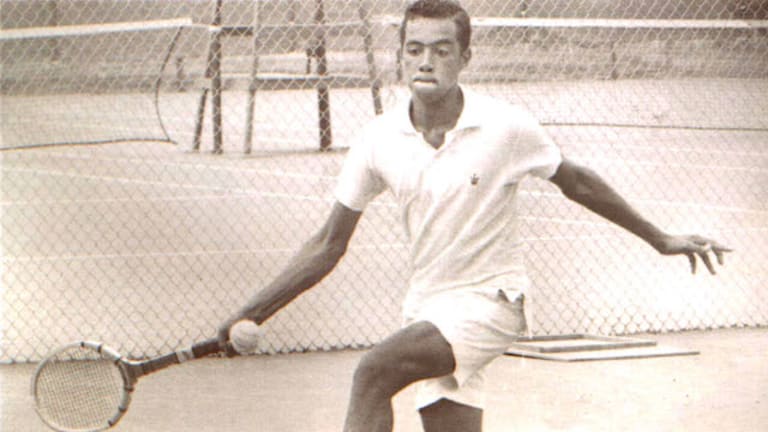

What those spectators saw and heard was a mismatch. Two years earlier, Budge had won the calendar-year Grand Slam and was still the world’s best player. McDaniel was the champion of the American Tennis Association, the game’s equivalent of baseball’s Negro Leagues, but he had never had the opportunity to play at the sport’s most famous venues or against its toughest competition.