Fifty Years of the WTA

Chapter 1: Before the “Original 9,” there was Gladys Heldman, who launched the women's tennis revolution

By Jan 24, 2023Fifty Years of the WTA

As the 50th year of the WTA Tour comes to an end, a look ahead to its next fifty

By Dec 31, 2023Fifty Years of the WTA

A spirit of activism has always been a part of the WTA tour

By Dec 11, 2023Fifty Years of the WTA

Chapter 10: From Venus and Serena to Naomi and Maria, the WTA's crossover icons are on a first-name basis

By Nov 07, 2023Fifty Years of the WTA

Approaching 80, Billie Jean King is still globetrotting for investment in women’s sports

By Oct 12, 2023Fifty Years of the WTA

Serena vs. BJK, Evert vs. Barty, Graf vs. Sharapova: Across 50 years, imagine these match-ups between WTA greats

By Oct 06, 2023Fifty Years of the WTA

The Room Where It Happened: WTA Tour marks 50 years, backwards and forwards

By Aug 26, 2023Fifty Years of the WTA

Chapter 8: The WTA tour's global reach extends to nations and athletes everywhere

By Aug 25, 2023Fifty Years of the WTA

Chapter 7: 50 years after the WTA was created, its future is now—and never-ending

By Jul 15, 2023Fifty Years of the WTA

Chapter 6: Austin, Graf, Sharapova and Raducanu exemplify the WTA's capacity for teenage stars

By Jun 21, 2023Fifty Years of the WTA

Chapter 1: Before the “Original 9,” there was Gladys Heldman, who launched the women's tennis revolution

Watch the first-part of our year-long series on the 50th anniversary of the WTA Tour.

Published Jan 24, 2023

Advertising

Advertising

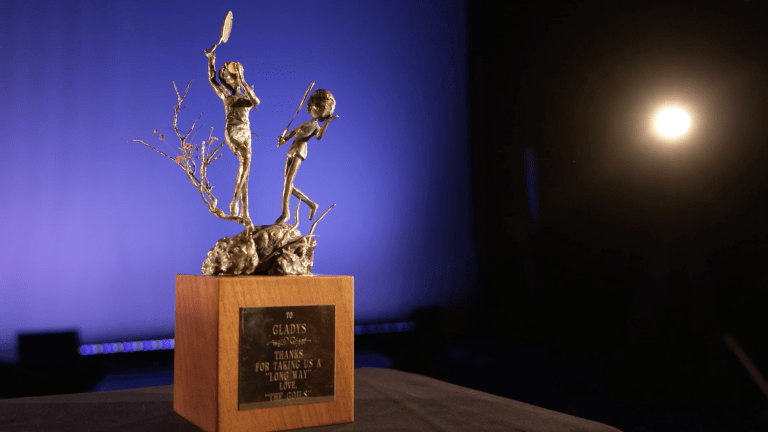

"Thanks for taking us a 'long way,'" reads the plaque on this bronze sculpture—given to Gladys Helman from "The Goils." It currently resides at the International Tennis Hall of Fame in Newport, R.I., which will commemorate the WTA Tour's 50th anniversary this year.

Advertising

Advertising

Advertising

Gladys Heldman died on June 22, 2003. At the 2019 US Open, Billie Jean King, Rosie Casals and members of the Original 9 honored Heldman at Flushing Meadows.

© Getty Images