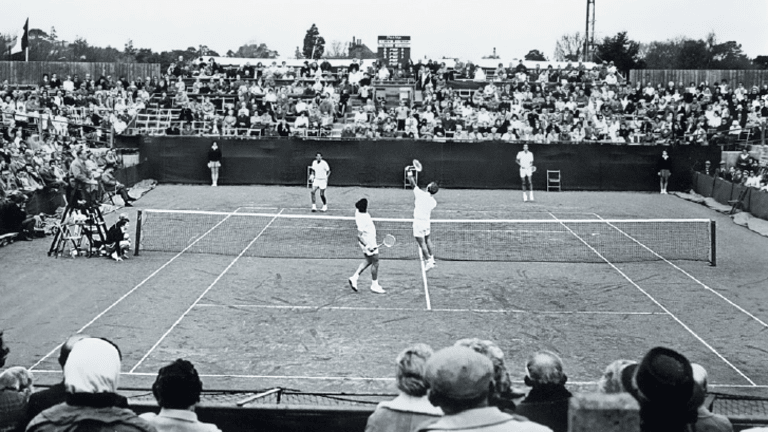

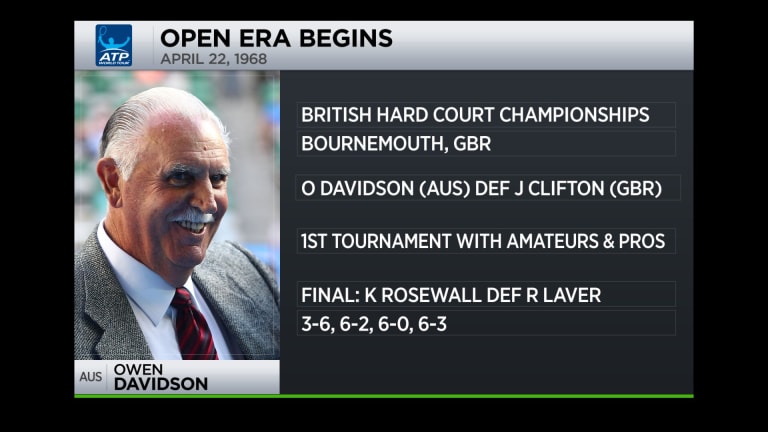

Nineteen-sixty-eight was a year of revolution, when cities from Tokyo to Chicago to Paris to Prague were convulsed with protest. Things got so wild that even the staid old sport of tennis joined the fun in the sleepy seaside resort town of Bournemouth, England. That’s where, at 1:43 p.m. on April 22, in front of 100 hardy fans and a shivering dog, a 22-year-old from Scotland named John Clifton squinted up through the mist and hit the first serve of tennis’ Open era.

As revolts go, this may sound a little mild. But that week at Bournemouth, tennis channeled the anarchic spirit of the 1960s. It was a decade when traditional divisions were erased and age-old hierarchies came crashing down. Black and white in the American south; men and women in workplaces and on college campuses; fine art and commercial art; jazz and rock: What had seemed like essential distinctions as the decade started had begun to dissolve by its end. In 1967, the U.S. Supreme Court invalidated laws prohibiting interracial marriage; in ’69, female students were admitted to Yale and Princeton. In Bournemouth that spring, tennis added its own once-unthinkable commingling to the ’60s cocktail party: The end of the distinction between amateur and professional.

That division had been at the heart of tennis since its invention a century earlier in Victorian England. Amateur was the athletic version of “gentleman,” the man of inherited means who didn’t need to play a sport for money. The professional, by contrast, had to swing for his living. For decades, the two groups traveled on separate but unequal tracks. The amateurs gamboled on the grass at the Grand Slams while grabbing appearance money under the table. The pros drove through the small-town wilderness on one-night barnstorming tours; any place where they could put together a semblance of a paying audience would do.

WATCH: Our Stories of the Open Era video series, on cultural tennis icons