Tata, tata, tata. The sound advances like a baby’s rattle bouncing across a darkened room. My grip on the junior racquet tightens. I swipe where I think the moving target will be. It’s more of a scoop than an orthodox forehand, long on hand and wrist, short on footwork or shoulder rotation, with no backswing to speak of. Smack! Tata, Tatatatata. I stand there, blindfolded and smiling, proud to have sent a ball careening somewhere, anywhere.

“Let’s try that again,” I say. But this time I ask that the toss not go perfectly into the expected path of my stroke. I want to see if I can track and hit a foam ball stuffed with jangly ball bearings using only my ears to pinpoint its location. Tata, tata. I take two hesitant steps to the right. Tata, scoop! Whoosh. Where is the ball? I try again. Again, air. It is my first lesson in blind tennis.

My lesson occurred back in 2012 and my instructor was Sejal Vallabh of the volunteer organization Tennis Serves, which she founded to pair sighted high school tennis players with visually impaired students at such places as Lighthouse International in New York City, Perkins School for the Blind in Watertown, MA, and the California School for the Blind in Fremont, CA. My experience was not unusual for a blind tennis beginner, she says—many of her students often feel frustrated at first. But once they start making contact with the ball, says Vallabh, they “gain the confidence to be able to do it again. That’s when it becomes really exciting.”

One of the athletes at Perkins was Dan Guilbeault, an affable teenager who had gradually lost almost all his sight after being treated for a brain tumor when he was 3.

“I can only see your shadow,” he says. “And that’s only faint.” He played multiple sports growing up, but as his vision dimmed, “I never thought I would be able to play tennis,” he says.

When he heard that tennis classes would be offered at Perkins, Guilbeault seized the opportunity. “It actually became very easy for me,” he says. “I kind of wish they had this for public school kids who are blind all across the country.” Unlike traditional adaptive sports for the blind like goalball or “contact” wrestling, he adds, “Everybody knows the game of tennis.”

But, as everybody also knows, tennis requires visual acuity and hand-eye coordination to swat a small yellow ball with pace and precision. Your coach commands you ad nauseam to “keep your eye on the ball.” You say “good eyes” to your doubles partner when he or she lets the ball sail long. At the highest levels of the game, players make split-second decisions based on the direction of the ball, the amount and angle of its spin, the positioning of the net and lines in relation to the ball, and in the periphery, whether the opponent is favoring one side.

So, how is blind tennis possible? Scientists have found that the visual cortex—the part of the brain that processes what your eyes see—can also process auditory and tactile information. Blind people can also have visual perception, says Dr. Robert Gotlin, director of orthopedic and sports rehabilitation at Beth Israel Medical Center in New York City. “They can perceive objects in space using other senses.”

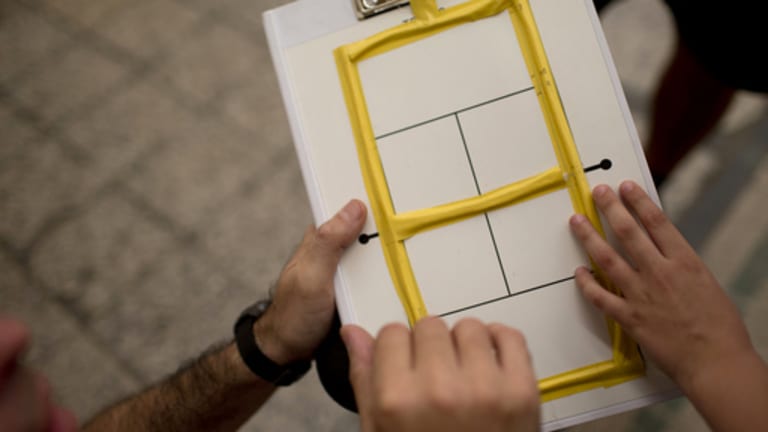

The sport is also modified. In addition to using a sound-adapted foam ball (for safety and lower bounces), it has a smaller court with raised lines, a lower net and shorter racquets, and players are allowed up to three bounces, depending on the severity of the visual impairment.