Instruction

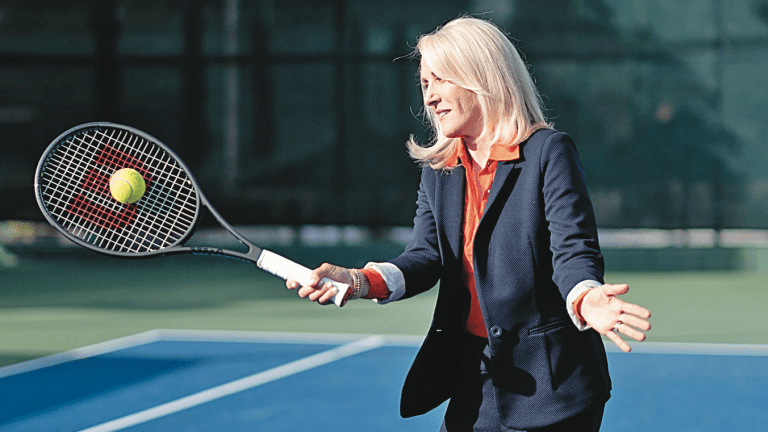

Building Blocks to Success: Tracy Austin helps your game

By Mar 09, 2022Instruction

Court of Appeals: Water Break

By May 20, 2023Instruction

Toni Nadal: With improved backhand, Casper Ruud "can be No. 1"

By Nov 21, 2022Instruction

Quick Tip: Add a rocking motion to the start of your serve

By Nov 16, 2022Instruction

Tennis Channel Academy: Rectifying Road Rage

By Oct 13, 2022Instruction

Tennis Channel Academy: Is the Lesson Model Broken?

By Oct 12, 2022Instruction

Breaking The Rules: Time to abandon the net touch?

By Oct 11, 2022Instruction

Mission Transition: How to bring your game from baseline to net (Part 3 of 3)

By Oct 03, 2022Instruction

Mission Transition: How to bring your game from baseline to net (Part 2 of 3)

By Oct 03, 2022Instruction

What can be applied from Carlos Alcaraz, Casper Ruud to your game? How to enjoy the competitive process

By Sep 12, 2022Building Blocks to Success: Tracy Austin helps your game

Without proper balance and an effective unit turn, your shots won’t be at their best. Here’s how to improve them both—and see the payoff.

Published Mar 09, 2022

Advertising

Advertising

In order to ensure hitting a shot with proper balance, everything starts with a good split step. The idea is to keep your body aligned.

© Jordaan Sanford

Advertising

The unit turn is what lets you load, store and deploy energy so that you can maximize the kinetic chain. This starts from the ground with the feet, on up to the legs, hips, torso, and shoulders.

© Jordaan Sanford

Advertising

At the most, take your racquet back no further than a little behind your right shoulder. As you turn, you should be able to see the racquet the entire time.

© Jordaan Sanford