David Dinkins was a New York City mayor, and a tennis superfan

By Nov 24, 2020Ben Shelton: European football's newest superfan? Lefty making most of Munich debut

By Apr 15, 2025Casper Ruud, Stefanos Tsitsipas open Barcelona bids in quest to halt further ranking slides

By Apr 15, 2025Jan-Lennard Struff sees Munich title defense bid as 'perfect opportunity' to turn 2025 around

By Apr 14, 2025Andrey Rublev storms to 100th ATP 500 win of career with opening victory in Barcelona

By Apr 14, 2025Monte Carlo takeaways: Alcaraz wins by playing for himself, one-handed backhands hold firm

By Apr 14, 2025Alexandra Eala: The reality of travel and difficulty of securing visas with a Philippine passport

By Apr 14, 2025Aryna Sabalenka takes her first crack at Iga Swiatek's clay-court supremacy in Stuttgart

By Apr 14, 2025ATP Challenger Tour: History made for Felipe Meligeni Alves

By Apr 14, 2025Carlos Alcaraz surpasses 40 million dollars in career prize money after winning Monte Carlo

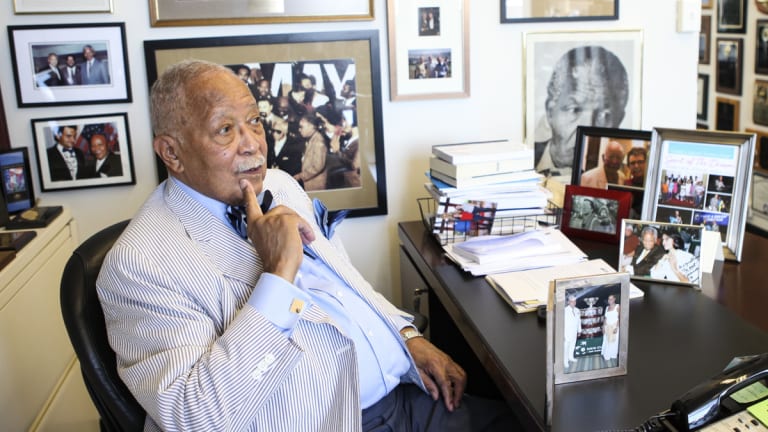

By Apr 14, 2025David Dinkins was a New York City mayor, and a tennis superfan

Dinkins helped reroute jets that once roared out of LaGuardia airport during the US Open, but he may have been most proud of the many years he spent as a USTA board member, and what he was able to accomplish there.

Published Nov 24, 2020

Advertising

David Dinkins was a New York City mayor, and a tennis superfan

© anita aguilar

Advertising

David Dinkins was a New York City mayor, and a tennis superfan

Advertising

David Dinkins was a New York City mayor, and a tennis superfan

Advertising

David Dinkins was a New York City mayor, and a tennis superfan

Advertising

David Dinkins was a New York City mayor, and a tennis superfan

Advertising

David Dinkins was a New York City mayor, and a tennis superfan

© anita aguilar

Advertising

David Dinkins was a New York City mayor, and a tennis superfan

© anita aguilar

Advertising

David Dinkins was a New York City mayor, and a tennis superfan