Decades later, Renée Richards' breakthrough is as important as ever

By Steve Tignor Mar 31, 2021FIRST LOOK: Coco Gauff to debut new Miu Miu x New Balance tennis collection in Rome

By Stephanie Livaudais Apr 23, 2025The Oeiras Open, which Carlos Alcaraz won four years ago, has one of the most beautiful Center Courts in the world

By Florian Heer Apr 23, 2025Reilly Opelka's latest 'rating' revealed: the views from his hotel room in Madrid

By Baseline Staff Apr 23, 2025Alexandra Eala vs. Iga Swiatek: Where to Watch, Madrid Preview, Betting Odds

By TENNIS.com Apr 23, 2025Italian teenager Federico Cina, 18, scores second ATP Masters 1000 victory with Madrid win

By Associated Press Apr 23, 2025Lithuanian-born, Spanish-trained Vilius Gaubas is ready to take on the world

By Florian Heer Apr 23, 2025Joao Fonseca vs. Elmer Moller: Where to Watch, Madrid Preview, Betting Odds

By TENNIS.com Apr 23, 2025Learner Tien vs. Marcos Giron: Where to Watch, Madrid Preview, Betting Odds

By TENNIS.com Apr 23, 2025WATCH: Denis Shapovalov is still not over Diego Dedura’s over-the-top celebration

By Baseline Staff Apr 23, 2025Decades later, Renée Richards' breakthrough is as important as ever

At an anarchic US Open, the transgender tennis player made a pioneering point.

Published Mar 31, 2021

Advertising

Throughout Women's History Month, TENNIS.com will be highlighting some of the most significant achievements and moments that make our sport what it is today.

As Renée Richards walked through the winding, Tudor-lined lanes of Forest Hills, people from the neighborhood gathered around her to wish her luck. After seeing the ophthalmologist’s picture in the newspapers for months, the locals of Queens knew where she was going—the West Side Tennis Club—and the magnitude of what she was about to do.

It was August 1977, the closing weeks of the notorious Summer of Sam in New York City. Over three harrowing months, the crumbling metropolis had been rocked by terrorizing riots, a chaotic blackout and the frantic search for a serial killer. As autumn mercifully approached, though, tennis became the talk of the town, and Richards was, for the moment, the world’s most talked-about athlete.

In 1953, Richards had entered the men’s draw at the U.S. Nationals under the name Richard Raskind. Twenty-four years later—and two years after having sexual-reassignment surgery and changing her name—Renée was on her way to play her first match as a woman at the same event, now known as the US Open. To make it there, she had weathered a chromosome test, boycotts by her fellow players, the scrutiny of the media, a ban by the sport’s officials and a lawsuit to overturn that ban.

But Forest Hills wasn’t just the home of the Open; it was also Richards’ home. These tree-lined lanes were where young Richard had grown up, where he had learned to play tennis—and where he discovered as a child that he had a second, female self inside him, fighting to get out.

“People crowded ’round,” Richards recalled of her walk to West Side that day, “wishing me well on the same streets where I had skulked 30 years before, wearing my sister’s clothes.”

Now, at 43, she felt free.

“There was tennis to be played,” Richards said. “My heart lightened at the prospect. I was about to do the thing that had saved me so many times before—and on the greatest stage in the world, I would do it as Renée.”

Decades later, Renée Richards' breakthrough is as important as ever

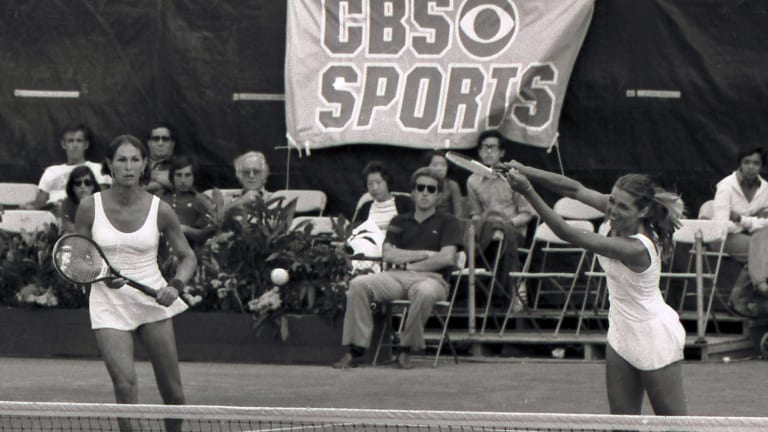

© AP1977

Advertising

Richards’ walk through the gates at West Side was the culmination of a 12-month whirlwind that had upended her life and her sport, and left her playing, as she put it, “tennis in a fishbowl.”

She had taken the plunge into that fishbowl in August 1976, when she entered her first pro tournament as a woman at the Orange Lawn Tennis Club in New Jersey. There had never been a debut quite like it. The Rolls Royce that took her to the grounds before her opening match was greeted by dozens of fans, autograph seekers and celebrity hounds. As the car approached the clubhouse, the mob surged toward it. Inside, Richards sank down in her seat. Was this private person ready for the public life that awaited her?

Just one year before, Dr. Richard Raskind, an accomplished athlete who had captained the men’s team at Yale two decades earlier, had undergone sexual-reassignment surgery. Soon after, as Dr. Renée Richards, she moved from New York to Newport Beach, CA, to start a new life. But there was one thing she couldn’t leave behind: her conspicuous skill at tennis.

After impressing the members at her new club, Richards agreed to enter a tournament in nearby La Jolla. A woman in the audience made the connection between the tall lefty who was mowing down the competition, and a story she heard about a tennis-playing doctor who moved west after having a sex change.

When a TV station subsequently—and erroneously—ran a report that Richards was a man masquerading as a woman, she became front-page news. Richards set the record straight at a press conference. The attention died down, and the paparazzi moved on. But one set of reports continued to irk her.

“Officials in the governing bodies of tennis,” Richards wrote in an autobiography, Second Serve, “were quoted as saying that I would not be allowed to participate in major championships for women because of my past as Richard Raskind.”

Richards had never been an activist, but after her story broke she received an avalanche of mail, many from minority communities, urging her to play. “The whole world seemed to be looking for me to be their Joan of Arc,” she said.

After some prodding, Richards decided to take on the role. She wanted “to prove that transsexuals as well as other persons fighting social stigmas can hold their heads up high.”

Among the letters Richards received was one from an old friend, Gene Scott. The former pro was angry at how Richards was being treated, so he invited her to enter the tournament he ran in New Jersey. When she accepted, 23 female players boycotted.

At the Orange Lawn Tennis Club that August, Scott was there to help Richards out of the Rolls Royce and through the crowd of gawkers. The clubhouse offered a respite from the masses, but she wasn’t free of the press. To get to her practice court, Richards slipped out a back window and down a fire escape.

By the time her match began, she was punch-drunk and exhausted. “Don’t fall down, Renée,” was all she could think.

Knowing that Howard Cosell was calling the match for a national television audience didn’t help. The only thing that did was the fact that her opponent, Kathy Beene, was even more nervous. Beene double-faulted 11 times, and Richards won in just 47 minutes.

Richards was front-page news again, though sportswriters didn’t know what to make of this new brand of athlete.

“At first, it seemed like a put-on,” Sports Illustrated wrote. “A transsexual tennis player? A 6'2" former football end in frilly panties and gold hoop earrings pounding serves past defenseless girls?”

UPI, in its report on her first-round match, described Richards as a “tall and attractive 42-year-old ophthalmologist.”

Decades later, Renée Richards' breakthrough is as important as ever

© AP

Advertising

Later that night in Manhattan, Richards took pride in what she had accomplished when she saw the next day’s Daily News. As her fellow New Yorkers leaned out of cab windows to shout their encouragement, she read a headline that could have been written for Jimmy Connors or Joe Namath: RENEE ROLLS IN NEW JERSEY OPENER

Richards’ victory took her to a dizzying new place in her public life, but it also brought her back home. The night before her match against Beene, she paid a surprise visit to her father, David, at the family’s house in Forest Hills. She was relieved when he greeted her as if nothing had changed. A few days later, David Raskind paid a surprise visit of his own when he showed up at Orange Lawn for Renée’s third match.

Tennis had been at the heart of their relationship. Years before, they had bonded during hitting sessions at the Sunrise Club in Queens, as both tried to escape the stressful intensity of life at home. There, young Richard was dominated by his mother and his older sister, who dressed him as a girl. By 9, he had begun to dress himself that way.

As a teen, Richard came across Man Into Woman, the autobiography of Lili Elbe, a transgender who was portrayed by Eddie Redmayne in The Danish Girl. Elbe’s story rang true for Raskind. From his teens through his 30s, his psyche was the site of a prolonged battle between his outer male self, and an inner female persona who was constantly fighting to get the upper hand.

“During this period,” Richards said, “I probably would not have survived without tennis. Athletics was the one constant in an otherwise uncertain world.”

On the surface, Richard Raskind was a success. He excelled at sports, graduated from Yale, became a surgeon, married and had a son, Nick. Underneath, though, he felt that he might “go mad” if he “continued masquerading as Dick.” At 40, Raskind underwent the three-and-half-hour procedure that set Renée free for good.

Decades later, Renée Richards' breakthrough is as important as ever

© AP

Advertising

When Richards’ run in New Jersey came to an end in the semis, against Lea Antonopolis, she thought she would repeat her breakthrough at the US Open. After all, that loss proved a woman could beat her.

Despite being certified as a woman by the state of New York, though, Richards was forced to take a chromosome test. She refused to take it at first; when she did, the result was ambiguous. After being denied entry into the 1976 US Open, Richards countered with a lawsuit.

During that time, Richards said she saw the “best and worst of women’s professional tennis.” Promoter Gladys Heldman risked WTA sanction when she invited Richards to play at her events. Billie Jean King’s World Team Tennis offered her a contract. Martina Navratilova encouraged Richards and later hired her as her coach. Others weren’t as welcoming: one opponent responded to Richards’ aces with a middle finger.

Help came from an unsavory, if effective, corner: Roy Cohn. The legendarily vicious consigliere to Joseph McCarthy and Donald Trump took Richards’ case. The tennis authorities never stood a chance. With a supportive affidavit from King, Richards won her suit.

Yet that wasn’t the end of the controversy. At the 1977 US Open, Richards drew Virginia Wade in the first round. Asked how she would feel if she lost to Richards, Wade said, “I’d demand that she be tested.” Wade said she was joking and was misquoted, but did admit she wasn’t “comfortable with the whole idea.” By the time the match started before a capacity stadium crowd, Richards and Wade weren’t speaking.

Wade, the ’77 Wimbledon champion, needn’t have worried; she beat a nervous Richards, 6–1, 6–4. But Richards settled down in doubles and reached the final with Betty Ann Stuart. She would eventually settle into the tour as well, climb to No. 20 in the world and coach Navratilova to No. 1. Richards found a home in women’s tennis, playing the game that had saved her so many times before.

Now 83, Richards lives in upstate New York, far from the spotlight. Controversial in 1977, she is hailed as a pioneer in 2017, a time when the world has watched Bruce Jenner become Caitlyn Jenner.

Richards remains a reluctant symbol. She has said she sees her gender status as a “part of life,” not a “way of life.”

“I am first and last an individual.”

Spoken like a tennis player. If Richards is a hero to the LGBT community, she should also be one to players and fans. She made the Open era live up to its name by forcing the game to welcome anyone with the courage to be herself.