Tennis.com Interview

Four decades ago, Terry Holladay was the WTA's pioneering mom

By Sep 21, 2023Tennis.com Interview

Jan-Lennard Struff sees Munich title defense bid as 'perfect opportunity' to turn 2025 around

By Apr 14, 2025Tennis.com Interview

Lorenzo Musetti manifested his 'special' week in Monte Carlo with first Masters 1000 final

By Apr 12, 2025Tennis.com Interview

No logic, just a feeling: Andrey Rublev "always knew" he wanted to work with Marat Safin

By Apr 07, 2025Tennis.com Interview

Brad Gilbert, Patrick McEnroe weigh in on U.S. men's tennis evolution

By Apr 05, 2025Tennis.com Interview

Patrick McEnroe decries Jannik Sinner suspension, tags Joao Fonseca as future star

By Apr 04, 2025Tennis.com Interview

On chicken farm, Danielle Collins embraces “crunchy granola lifestyle”

By Apr 03, 2025Tennis.com Interview

Feeling like a teenager, Alizé Cornet, 35, makes triumphant comeback from retirement

By Apr 02, 2025Tennis.com Interview

Danielle Collins launches iconic richsport merch collab

By Mar 07, 2025Tennis.com Interview

Zizou Bergs: From TikTok to Top 50 in Indian Wells?

By Mar 06, 2025Tennis.com Interview

Four decades ago, Terry Holladay was the WTA's pioneering mom

After giving birth in 1982, Holladay successfully petitioned the tour to return the following year without a ranking—an early application of what is now the protected ranking rule.

Published Sep 21, 2023

Advertising

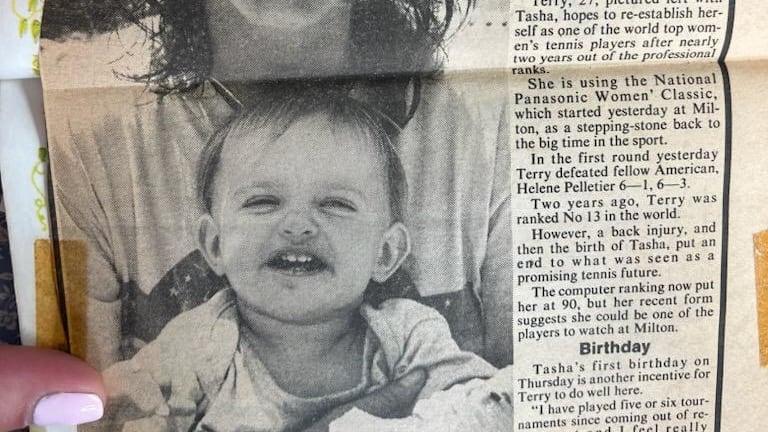

A newspaper clipping from Terry Holladay's playing days with young 'Tasha.

© Courtesy of Terry Holladay.

Advertising

Advertising

Terry Holladay and family, from left to right: Romyn, Tasha's first child; Terry's son, Louis; Terry's daughter, Maggie; Terry; Michael Tracy, Tasha's husband (holding River, Tasha and Michael’s second daughter); and Tasha.

© Courtesy of Terry Holladay.

Advertising

Terry Holladay and her three children, from left to right: Natasha, Louis, Terry, Maggie.

© Courtesy of Terry Holladay.