Australian Open

From mateship to lawsuits: the unfortunate decay of Australian tennis

By Jan 21, 2019Australian Open

Roger Federer to headline “Battle of the World No.1s” at Australian Open’s inaugural Opening Ceremony

By Dec 11, 2025Australian Open

Australia at Last: Reflections on a first trip to the AO

By Jan 29, 2025Australian Open

Alexander Zverev must elevate his game when it most counts—and keep it there

By Jan 27, 2025Australian Open

Jannik Sinner draws Novak Djokovic comparisons from Alexander Zverev after Australian Open final

By Jan 26, 2025Australian Open

Alexander Zverev left to say "I'm just not good enough" as Jannik Sinner retains Australian Open title

By Jan 26, 2025Australian Open

Jannik Sinner is now 3-0 in Grand Slam finals after winning second Australian Open title

By Jan 26, 2025Australian Open

Taylor Townsend and Katerina Siniakova win second women's doubles major together at the Australian Open

By Jan 26, 2025Australian Open

Madison Keys wins her first Grand Slam title at Australian Open by caring a little bit less

By Jan 25, 2025Australian Open

Henry Patten, Harri Heliovaara shrug off contentious first set to win Australian Open doubles title

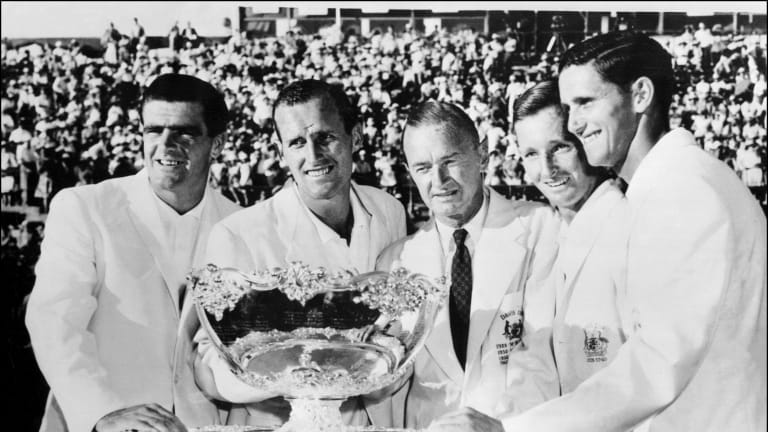

By Jan 25, 2025From mateship to lawsuits: the unfortunate decay of Australian tennis

Bernard Tomic's public takedown of Lleyton Hewitt is just the most glaring example of the once-great tennis nation's fall from grace.

Published Jan 21, 2019

Advertising

From mateship to lawsuits: the unfortunate decay of Australian tennis

© AFP/Getty Images

Advertising

From mateship to lawsuits: the unfortunate decay of Australian tennis

© AFP/Getty Images

Advertising

From mateship to lawsuits: the unfortunate decay of Australian tennis