Tennis.com Interview

Holding Court with…Vic Seixas, who turns 100 today

By Aug 30, 2023Tennis.com Interview

Jan-Lennard Struff sees Munich title defense bid as 'perfect opportunity' to turn 2025 around

By Apr 14, 2025Tennis.com Interview

Lorenzo Musetti manifested his 'special' week in Monte Carlo with first Masters 1000 final

By Apr 12, 2025Tennis.com Interview

No logic, just a feeling: Andrey Rublev "always knew" he wanted to work with Marat Safin

By Apr 07, 2025Tennis.com Interview

Brad Gilbert, Patrick McEnroe weigh in on U.S. men's tennis evolution

By Apr 05, 2025Tennis.com Interview

Patrick McEnroe decries Jannik Sinner suspension, tags Joao Fonseca as future star

By Apr 04, 2025Tennis.com Interview

On chicken farm, Danielle Collins embraces “crunchy granola lifestyle”

By Apr 03, 2025Tennis.com Interview

Feeling like a teenager, Alizé Cornet, 35, makes triumphant comeback from retirement

By Apr 02, 2025Tennis.com Interview

Danielle Collins launches iconic richsport merch collab

By Mar 07, 2025Tennis.com Interview

Zizou Bergs: From TikTok to Top 50 in Indian Wells?

By Mar 06, 2025Tennis.com Interview

Holding Court with…Vic Seixas, who turns 100 today

As humble and upbeat as ever, the Grand Slam champion from Philadelphia celebrates his centennial birthday.

Published Aug 30, 2023

Advertising

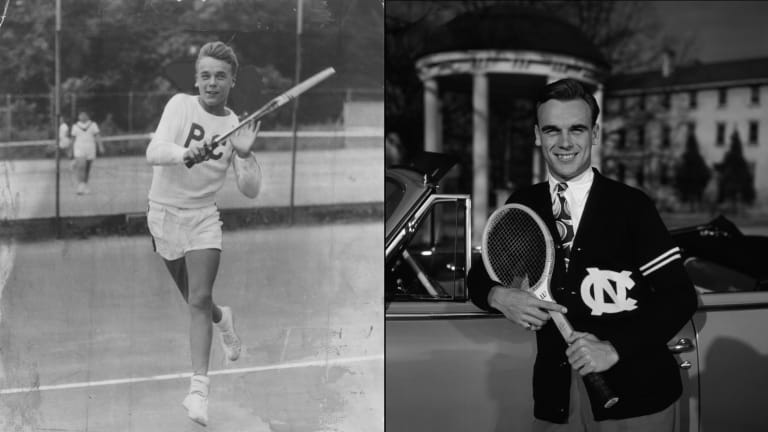

Vic Seixas in his teens, at the William Penn Charter School in Philadelphia, and at the University of North Carolina.

Advertising

Advertising

Advertising

Advertising

Seixas at the 2014 US Open, and more recently, with his friend Allen Hornblum. “Despite his physical infirmities, he’s always upbeat and positive,” says Hornblum. “The guy was built to look forward and push on, no matter the obstacles.”