How Craig O’Shannessy brings the analytics revolution to tennis

By Steve Tignor Jan 17, 2020Australia at Last: Reflections on a first trip to the AO

By Jon Levey Jan 29, 2025Alexander Zverev must elevate his game when it most counts—and keep it there

By Peter Bodo Jan 27, 2025Jannik Sinner draws Novak Djokovic comparisons from Alexander Zverev after Australian Open final

By Steve Tignor Jan 26, 2025Alexander Zverev left to say "I'm just not good enough" as Jannik Sinner retains Australian Open title

By Matt Fitzgerald Jan 26, 2025Jannik Sinner is now 3-0 in Grand Slam finals after winning second Australian Open title

By TENNIS.com Jan 26, 2025Taylor Townsend and Katerina Siniakova win second women's doubles major together at the Australian Open

By Associated Press Jan 26, 2025Madison Keys wins her first Grand Slam title at Australian Open by caring a little bit less

By Steve Tignor Jan 25, 2025Henry Patten, Harri Heliovaara shrug off contentious first set to win Australian Open doubles title

By Associated Press Jan 25, 2025Aryna Sabalenka takes a rare loss in Australian Open slugfest

By Pete Bodo Jan 25, 2025How Craig O’Shannessy brings the analytics revolution to tennis

A key member of the team that helped Novak Djokovic reassert himself in 2018 and 2019, can O’Shannessy change how the sport is played?

Published Jan 17, 2020

Advertising

Craig O’Shannessy grew up like any other young tennis fanatic. He would run home from school each day, then run to the courts so he could get in as much play as possible before the sun set.

There were plenty of courts, including 25 made of grass, in his hometown of Albury, Australia. The city of 47,000 in New South Wales was small, but it loomed large in tennis history. Margaret Court and Dianne Fromholtz honed their world-class games there. And while the great Australian tennis empire built by the country’s Davis Cup captain, Harry Hopman, had begun its decline by the time O’Shannessy picked up a racquet in the 1970s, the culture around the sport was still strong.

“Adults and kids went out and played matches together all day,” O’Shannessy remembers. “There was no drilling, no lessons. We just played until it was too dark to see the ball.”

O’Shannessy, like every self-respecting Aussie of his day, was a serve-and-volleyer. Without lessons, his technique was raw, but he knew how to hide his weaknesses. His backhand volley grip was so bad, he says, he learned how to run around it and hit a forehand volley instead—not an easy thing to pull off when you’re rushing the net.

“Fortunately, quickness was something I could do,” O’Shannessy says with a laugh.

More important for his future career, O’Shannessy’s technical shortcomings also made him a keen student of what was happening on the other side of the net.

“My game wasn’t polished, so I had to rely on strategy,” he says. “I was always focusing on what my opponent was doing.”

How Craig O’Shannessy brings the analytics revolution to tennis

Advertising

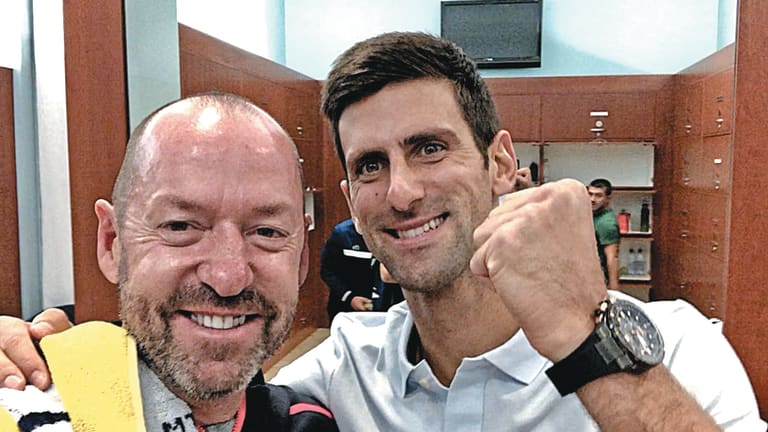

Tennis’ answer to baseball sabermatrician Bill James, O’Shannessy embraces advanced stats and searches for opportunistic patterns in play. But he’s not keeping his perspective under lock and key. The 53-year-old has been spreading his numbers-based gospel for years, working with a variety of players and showing no signs of slowdown. (Craig O’Shannessy)

O’Shannessy, a lefty, wasn’t destined to be the next Rod Laver, but he was good enough to play No. 1 at Baylor, where he graduated with a journalism degree in 1991. Faced with a choice between writing and coaching after college, he chose the latter. O’Shannessy believed there were blind spots in tennis’ traditional coaching methods, ones he felt he was equipped to fill.

“Everyone’s philosophy was, ‘Just worry about your own game,’” O’Shannessy says. “But winning matches isn’t just about playing your game. It’s about figuring out how to beat a specific opponent.”

Even more frustrating for O’Shannessy was the data—or lack thereof—that coaches and players relied on for their game plans.

“The statistics were so primitive,” he says. “Everyone was guessing about what worked. Was serve and volley dead? Should you hit more forehands than backhands? I didn’t want to guess, so I started counting.”

O’Shannessy felt like he was onto something at the 1995 Australian Open, when a 17-year-old he was working with, Dally Randriantefy of Madagascar, came out of qualifying to reach the third round.

“Her first-round opponent sliced her backhand, and she couldn’t keep it deep consistently,” O’Shannessy recalls. “I said, ‘If she hits three backhand slices in a row, move in, because one of them will be short, and she can’t pass you with it.”

In a surprise, Randriantefy won that match, and her next one, before losing to eventual champion Mary Pierce. It was obvious to O’Shannessy that, contrary to conventional tennis wisdom, a player could go a long way with a scouting report and a strategy. Now all he needed were the numbers.

Craig O’Shannessy has worked with Novak Djokovic—a legend that the Alcaraz has already been compared to—and has studied the 19-year-old in victory and defeat.

Advertising

O'Shannessy played NCAA tennis at Baylor, before shifting to coaching in the sport. (Craig O'Shannessy)

This month, O’Shannessy will return to the Australian Open. Much has changed, in his career and in coaching, since his breakthrough in Melbourne 25 years ago. Instead of working with a teenage qualifier, he’ll work with a number of clients that include 2019 US Open semifinalist Matteo Berrettini—after helping Novak Djokovic add four majors to his career haul in 2018 and 2019. Instead of having to guess what’s happening on the court, he’ll be armed with numbers that get more detailed by the day. Instead of feeling like a lone voice in the statistical wilderness, he’ll be at the forefront of a data movement that may transform tennis in the same way that it has transformed baseball and basketball.

Now 53 and living in Austin, TX—with his wife, Kelly, and two children, Rourke and Riley—O’Shannessy has become the face and voice of analytics in tennis. Upbeat and gregarious, he defies the stereotype of the stat nerd. When he’s not drawing up battle plans for Berrettini and other pros, he serves as a strategy guru during Grand Slam broadcasts, writes for the ATP’s website, travels the world delivering presentations, and runs Brain Game Tennis, the self-described “No. 1 Strategy Website.”

According to O’Shannessy, you only have to look at last year’s Australian Open men’s final, between Djokovic and Rafael Nadal, to see the power of analytics. Nadal came into the match looking close to invincible, only to be dismantled by Djokovic in three quick sets. While Djokovic was rightly praised for his play, from O’Shannessy’s perspective, there was more to the performance than met the eye.

The Serbian may have made it look easy, “but a lot of work went into that match,” says O’Shannessy, who joined Djokovic’s team as a tactical analyst in 2017 (the pair parted aways at the end of 2019). Their team pored over data that told them where Nadal liked to hit the ball and where he didn’t, giving Djokovic a clear idea of what he wanted to do.

TANDON: The role of analytics in tennis is on a long, slow rise

How did O’Shannessy get from Randriantefy to Djokovic? The road was long, but two epiphanies helped him turn his theories into reality.

The first came in 2005, with the advent of Dartfish video technology. Using a Dartfish recording, O’Shannessy could analyze a match in greater depth and specificity.

“We knew how many winners and errors players hit, but now you could see where a player made them,” O’Shannessy says. “Patterns began to jump out; you might see a player make 10 errors from the same spot. Tennis can look like chaos, but it’s really the same things happening over and over.”

How Craig O’Shannessy brings the analytics revolution to tennis

Advertising

From cryotherapy to veganism to mental training, Djokovic has left no stone unturned in finding ways to improve. With O’Shannessy, he’s turned to big data, and what it can reveal in scouting opponents. (Craig O’Shannessy)

O’Shannessy began to believe that far too much emphasis had been put on winners—and especially unforced errors—and that the stat to focus on is the “forced error.”

“Worrying about unforced errors is keeping this sport in the dark ages,” he says. “Winning matches isn’t about playing perfect tennis or getting one more ball back. It’s about putting your opponent in places where he’s more likely to miss.”

O’Shannessy’s second epiphany came a few years later, when IBM, which creates statistical spreadsheets

of matches, began to include a breakdown of rally lengths: how many were 1-4 shots; how many were 5-8; how many lasted 9 or more. O’Shannessy was struck by the fact that 70 percent of points were in the 1 to 4 shot range, and that the player who won the majority of those points won the match the vast majority of the time.

“In all of the analysis of tennis, we never considered rally length,” he says. “We remember the long rallies, but it had never hit me that, on average, each player will only touch the ball twice in a point. Everyone trains to win long points; what we need to do is win the short points.”

In that sense, analytics—depending on how much you buy into it—reveals the same thing about tennis that it has revealed about basketball and baseball: patience isn’t necessarily a virtue. In basketball, statistics have shown that the risk of attempting three-point shots is worth the reward. In baseball, the low-percentage home run swing has been prioritized over the seemingly more sensible base hit. O’Shannessy thinks the numbers show that tennis is due for an analogous shift.

“We have kids go out and hit a million balls in a row in practice and everyone is happy, the kids are happy, the parents are happy,” he says. “But that’s not what happens in a match. Meanwhile, we don’t practice our serves enough and almost never practice our returns, and those are the shots we hit the most.”

How Craig O’Shannessy brings the analytics revolution to tennis

© 2019 Getty Images

Advertising

Last year’s Australian Open final between Djokovic and Nadal was unexpectedly one-sided—a shock to many, but not necessarily to O’Shannessy. Djokovic rolled, the Aussie wrote on the ATP’s website, “by doing exactly what conventional wisdom says you shouldn’t do—play to your opponent’s best shot... With Nadal always looking to protect to the right, Djokovic attacked to the left.” (Getty Images)

If consistency is overemphasized, according to O’Shannessy, the attacking forehand is underemphasized. For him, the most effective servers are the ones who use their serves to set up their forehands—the “serve plus one,” as it’s known in today’s lingo. As much as people love to watch Stan Wawrinka or Dominic Thiem uncork their one-handed backhands, it’s their forehands that do the most damage. And while Djokovic’s two-handed backhand is celebrated, O’Shannessy’s data shows that his forehand is the more effective shot, and one he should be hitting more often.

“The Spanish system is about hitting balls in the sun all day, but that’s not how Rafa wins,” O’Shannessy says. “He uses his serve and works the rallies so he can hit an offensive forehand.”

O’Shannessy’s system has produced results. He helped mastermind Dustin Brown’s upset win over Nadal at Wimbledon in 2015. He had a “come to Jesus” moment with Kevin Anderson about the South African’s game that eventually led to his rise into the Top 10. Last year at Wimbledon, O’Shannessy helped Alison Riske upset his countrywoman Ash Barty. At the US Open, he helped guide Berrettini to his first Grand Slam semifinal. In the wake of his success, other agencies, like Golden Set Analytics and Tennis Stat, have begun to offer statistical services to players at all levels.

“All the big guys are using data analysis, they just don’t like to talk about it,” Alexander Zverev told The Daily Telegraph last year. “It’s a big part of the game now.”

“I like analytics, and I like what Craig does,” says Brad Gilbert, who coached Andre Agassi and Andy Roddick. “I think he’s helped Novak a lot with information on his opponents’ strengths and weaknesses.”

But Gilbert, who describes himself as “a little bit old school,” sees limits to statistical analysis. Whatever the numbers say about what works overall, you still have to know your player, and there’s still value in being consistent.

“Most points might be short, but what if you’re [David] Ferrer or [Simona] Halep, someone who wins with their legs?” Gilbert says. “I know Andre felt most comfortable when he wasn’t making errors.”

How Craig O’Shannessy brings the analytics revolution to tennis

© AP

Advertising

In working with O’Shannessy, Alison Riske and Matteo Berrettini have executed tactical changes based on their opponents’ tendencies. Each player finished 2019 at career-high rankings: Riske, who reached the Wimbledon quarterfinals, at No. 18; Berrettini, who qualified for the ATP’s season-ending championships, at No. 8. (AP Images)

Gilbert also believes that top players can go to places where stats can’t follow. He points to Pete Sampras’ win over Agassi in the 1999 Wimbledon final as an example. Coming into the match, Sampras hadn’t gone for broke much on his second serve.

“We thought Andre could attack it,” Gilbert says about the serve. “But Pete basically said, ‘That’s not happening to me.’ He elevated his speed, and served lights out.

“The patterns tell you a lot, especially with guys in the 80 to 100 ranking range. But the best guys can break the patterns. I’m still a believer in the greatness of the human element.”

For Gilbert, O’Shannessy’s success may be about more than just his math skills. It may also be because he offers something that good tennis coaches have always offered: personality.

“He’s can instill confidence, and that’s a lot in my book,” Gilbert says. “I mean, I like listening to him, too.”

When O’Shannessy talks about his childhood afternoons spent serving and volleying on grass courts in Albury, he makes it sound like a lost tennis utopia. Has he recovered some of that world in his statistical work? In those days of Aussie dominance, the points were short, attacking was the name of the game, and the best way to win was also the quickest. Maybe, if we believe O’Shannessy’s data, the sport really hasn’t changed all that much. Where it was once about serve and volley, now it’s about the serve and the forehand.

“Arguing about the game is fun, and getting pushback is fun,” O’Shannessy says with a laugh. “Especially when you’re the guy with the numbers to back it up.”

Editor's Note: Following the initial release of this story in Tennis Magazine, news of Djokovic and O'Shannessy parting ways became public. This version has since been amended to reflect that update.

How Craig O’Shannessy brings the analytics revolution to tennis