Jeanne Moutoussamy-Ashe's idea to resolve Arthur's statue struggle

By Steve Tignor Sep 13, 2020Who is Diego Dedura-Palomero? Meet Germany’s latest teenage star

By Emma Storey Apr 17, 2025Rafael Nadal to be honored with 'exceptional' tribute on opening day of Roland Garros

By Associated Press Apr 17, 2025Mirra Andreeva belts 'Happy Birthday' song to coach Conchita Martinez in Stuttgart

By Baseline Staff Apr 16, 2025Ben Shelton uses altitude to his advantage, joins Alexander Zverev in Munich quarterfinals

By TENNIS.com Apr 16, 2025Iga Swiatek in Stuttgart: From clay court to carpool karaoke!

By Franziska Bruells Apr 16, 2025Thorne taps Ben Shelton to launch new on-the-go performance line

By Stephanie Livaudais Apr 16, 2025Lois Boisson had the perfect response to Harriet Dart deodorant controversy

By Baseline Staff Apr 16, 2025Dominic Thiem ‘loves’ watching Jakub Mensik and Joao Fonseca

By Baseline Staff Apr 16, 2025Ben Shelton: European football's newest superfan? Lefty making most of Munich debut

By Emma Storey Apr 15, 2025Jeanne Moutoussamy-Ashe's idea to resolve Arthur's statue struggle

Richmond, and its monument to Arthur Ashe, have been at the center of a struggle over U.S. history this summer. Can the legendary humanitarian's legacy be brought back to his community?

Published Sep 13, 2020

Advertising

Over the last three months, the statue of Robert E. Lee on Monument Avenue in Richmond, Va., has come to embody all of the confusion—the sense of a nation being pulled backward and forward in time, and being ripped apart in the process—that has swirled across America since the protests over the death of George Floyd began in June.

Those protests started where Floyd lived, in Minneapolis, and spread to the main streets of virtually every U.S. community. But what happened on Richmond’s main street produced the most profound change in the country’s landscape. One by one, four statues of Confederate leaders that had stood above Monument Avenue for more than a century were toppled. Only a court order temporarily stopped Virginia governor Ralph Northam from sending Lee out on the colossal bronze horse—named Traveler—that he rode in on.

When Lee’s effigy was erected in 1890, officials in Richmond lobbied successfully for it to be enlarged by its French sculptor, so that it would rise higher than the city’s statue of George Washington. Weighing 12 tons and towering 60 feet high on its stone base, it was a monument to the South’s Lost Cause, an attempt to drown Civil War defeat in sentimental grandeur. In 2020, the Lee statue, with that false grandeur stripped away and its plinth covered in political graffiti, has became a meeting place and a public forum where the country’s conflicts play out in miniature each day.

Seen on TV and in newspaper articles, Lee looks as if he’s on his own, a man and his horse on an island, the last statue standing. In reality, one other remains, 14 blocks and more than a mile down Monument Avenue. That distance is fitting, because the person it memorializes, Arthur Ashe, came from a very different side of Virginia and America than Lee. Ashe was a Wimbledon-winning tennis player and social activist who grew up in an all-Black Richmond neighborhood during the 1940s, ’50s and ’60s, the last decades of Jim Crow. Where Lee fought for the continuation of slavery in Virginia, and in the South, Ashe showed his city and state what a free Black man could achieve on a world stage.

Now that the dust has begun to settle on the summer of 2020, the memorials to these two men, and the conflicting causes they represented, are alone together on opposite sides of Monument Avenue. Where the base of Lee’s statue is adorned with “Black Lives Matter” and “BLM,” Ashe’s was sprayed with “White Lives Matter” in June (the words have since been erased). No one, in Richmond or in the nation, knows what’s going to happen next. But efforts are underway to write a more complete, and less Confederate-centric, history of the city. If a new project involving Ashe’s legacy is successful, his statue could be a major part of that revision.

Jeanne Moutoussamy-Ashe's idea to resolve Arthur's statue struggle

© Copyright 2020 The Associated Press. All rights reserved

Advertising

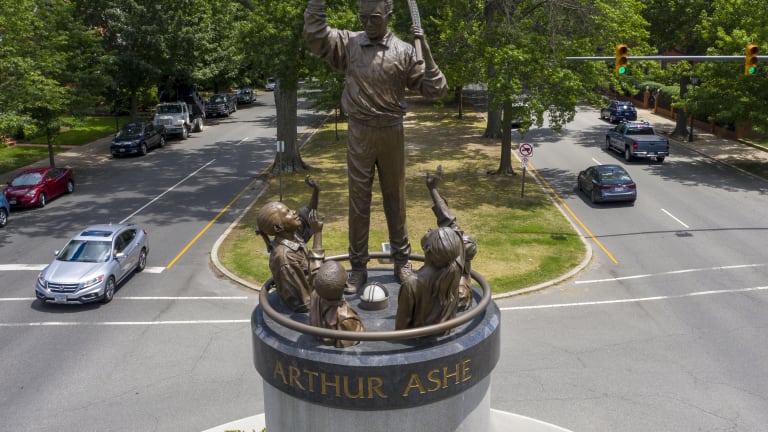

The Arthur Ashe monument, in Richamond, Va. (AP Images)

Originally, the idea was to place it alongside an African-American Sports Hall of Fame that Ashe hoped to develop in his hometown, as an extension of his book about the history of black athletes in America, A Hard Road to Glory. In 1992, he broached the idea to officials in Richmond, and the City Council approved plans for a 68,000-square-foot building to be constructed in the Jackson Ward district, where Ashe grew up. Around the same time, a Richmond sculptor named Paul DiPasquale expressed a desire to create a statue of Ashe, who had recently revealed that he had AIDS. Ashe approved of the idea, and of placing the statue at the Hall of Fame.

“Arthur doubted he would live long enough to witness its completion,” Raymond Arsenault wrote in his 2018 biography, Arthur Ashe: A Life. “But the idea of erecting a statue of his likeness appealed to him…In a limited but significant way, he reasoned, the statue might enhance a positive legacy in his hometown.”

One of the last things Ashe did before entering the hospital for the final time in early 1993 was send DiPasquale reference materials for the sculpture. Ashe wanted the work to include children and books, “to portray that knowledge is power,” and to show him in his warm-up suit and sneakers. By the time DiPasquale received the material, Ashe had passed away. After breaking down in tears at the sight of the package of photos Ashe had sent him, DiPasquale worked to make his vision a posthumous reality.

When Ashe died, his friend Douglas Wilder, the first African-American governor of Virginia, directed that his body lie in state in the Executive Mansion in Richmond; no Virginian had been honored in that way since Stonewall Jackson in 1863. Six-thousand people crammed the city’s Arthur Ashe Center for the three-hour memorial service, and many more lined the route where Ashe’s casket was carried—Yannick Noah was among the pallbearers—to his final resting place, in Woodland Cemetery, one of the Richmond area’s historically Black burial grounds. A few months later, mourners gathered there again to celebrate what would have been his 50th birthday. They listened as Maya Angelou spoke of a man “superb in love and logic.”

In the months after his death, Ashe’s statue began to take shape in DiPasquale’s hands, and in February 1994, Richmond officials gave the go-ahead for it to be placed on a yet-to-be-determined site on city property. When DiPasquale presented a plaster-cast version at an early unveiling ceremony, Governor Wilder went public with his preference for its location: Monument Avenue.

“These are heroes from an era which would deny the aspirations of an Arthur Ashe,” Wilder said. “He would stand with them, saying, ‘I speak, too, for Virginia.'”

There was no mention of Ashe’s hoped-for Hall of Fame, and the considerable funding needed to build it would never materialize. Instead, Wilder’s pronouncement was the opening salvo in a three-year war over the meaning of Monument Avenue and the appropriateness of a statue of an African-American in a Confederate memorial.

Officials who backed the idea received hate mail. Civil War re-enactors and the Sons of Confederate Veterans protested at City Council meetings. While there was support among the Black community, it wasn’t universal. Ray Boone, editor of the city’s most prominent African-American newspaper, the Richmond Free Press, wrote, “Identifying Arthur Ashe with racist generals of the Lost Cause would scandalize our hero’s shining memory. Subordinating him to a solid line of Confederate figures would intensify injustice, unfairly equating Arthur Ashe to a bronze row of history’s most traitorous villains.”

Boone’s uncompromising editorial sounds right at home in the Black Lives Matter era. But in 1996 it was Governor Wilder’s vision that prevailed. After multiple delays, DiPasquale’s statue of Ashe was installed at Monument Avenue and Roseneath Road, on July 10th, 1993, which would have been his 53rd birthday. Ironically, some members of the City Council were finally convinced to give their approval after hearing a speaker compare Ashe’s character and integrity to…Robert E. Lee’s.

Absent from the unveiling that day was Ashe’s widow, Jeanne Moutoussamy-Ashe. Early in 1993, she wrote her own editorial in the Richmond Times-Dispatch expressing her displeasure with the placement. “Richmond, can you remember that the ‘Arthur Ashe monument,’ as you call it now, was never meant to be just a monument to Arthur,” she wrote, while calling for the statue to be placed at the Hall of Fame. “Somehow, what Arthur wanted has been lost in the shuffle.”

Jeanne Moutoussamy-Ashe's idea to resolve Arthur's statue struggle

Advertising

The statue of Robert E. Lee on Monument Avenue, in 2020. (Wikimedia Commons)

She says the idea of having a statue on Monument Avenue would have been inconceivable to her husband. As a child, the street had been off-limits to him. And while Ashe’s teenage years coincided with the start of the Civil Rights Movement, the progress that was achieved elsewhere in the South only made Virginia’s politicians more determined to hold off integration at all costs. After Brown v. Board of Education outlawed segregated schools in 1954, Virginia began what became known as Massive Resistance, a set of laws designed to subvert Brown, one of which eliminated state funding for any public school that tried to integrate.

Ashe, who entered all-Black Maggie Walker High School in Richmond in 1958, experienced Virginia’s constrictions firsthand on the tennis court. He was annually denied entrance into tournaments held in Richmond’s all-white Byrd Park. By the time he was 15, he was ranked No. 5 in the nation, yet he was barred from playing the Mid-Atlantic Championships in his hometown. The Richmond Tennis Patrons Association, a group of local benefactors, paid for young white players to travel the country and compete, but they didn’t pay for Ashe.

“To the tennis fathers there, I was an untouchable,” he said. In 1959, the West Side Tennis Club in New York invited Richmond’s tennis officials to put together a boys’ traveling team, and suggested that it include the city’s best young black player, Ashe, and its best young white player, Tom Chewning. By then Ashe had read all about Chewning’s successes in the local papers; Chewning had to admit that he had never heard of Ashe.

“It was never an idea of Arthur’s to be on Monument Avenue,” Moutoussamy-Ashe reiterates today. “You have your white Confederates there, and then you have a Black favorite son. It felt divisive, and Arthur wasn’t divisive.”

For Moutoussamy-Ashe, that remains true even now that most of those Confederates are gone. She didn’t want Ashe’s legacy associated with the statues there, and she doesn’t want his presence on the avenue to be seen as “revenge” for them, either. The Hard Road to Glory Hall of Fame was never built in her husband’s old neighborhood, but Moutoussamy-Ashe would still like to see his statue placed in the Richmond that he knew. Specifically, she’d like to see it in Woodland Cemetery, where Ashe is buried.

To that end, Moutoussamy-Ashe has thrown her support behind a new project to restore Woodland and another African-American cemetery in the area, Evergreen. In August, Marvin Harris, a real-estate agent and the founder of the Evergreen Foundation, announced that he had raised $50,000 to purchase Woodland. With assistance from Henrico County and funding help from Moutoussamy-Ashe, Harris plans to clean up the century-old cemetery and showcase the history it contains.

“We’re going to bring this back to where it used to be,” he said at an announcement ceremony in Woodland earlier this month.

Like Ashe, Harris, 72, is a graduate of Maggie Walker High School, and he knew the Ashe family in Jackson Ward. Harris and his fellow students from the school’s Class of 1967 devised the idea of restoring these cemeteries, which had largely been ignored and obscured by overgrowth in recent years. Maggie Walker herself, the first black president of a bank in the U.S., is buried in Evergreen. Ashe is buried next to his mother, in one of four Woodland plots purchased by his father decades ago.

“It’s a big, amazing job that someone had to do,” says Harris, whose crews have begun to clear acres of disused land in Evergreen and Woodlands. “I didn’t know it had come to that state. It’s a daunting task.”

Harris believes that the project will not only restore these two pieces of historically Black Richmond, but draw visitors and teach them about the accomplished African-Americans who are buried there. Last year at Woodland, Harris ran across a family from the Midwest who had followed Ashe’s career, and had come to see his gravesite.

“I told them, ‘Come back in three years, we’ll have this place fixed up,’” Harris says.

Looking at Ashe’s headstone, which sits a few inches from his mother Mattie’s inside a low black fence, Harris says he can relate to his fellow Jackson Ward native.

“My mother’s interred in North Carolina,” Harris says. “I’ve lived my life here in Richmond, but I can understand him wanting to be next to her."

Jeanne Moutoussamy-Ashe's idea to resolve Arthur's statue struggle

Advertising

The gravestones of Arthur Ashe and his mother, Mattie, at Evergeen Cemetery. (Marvin Harris)

“I can remember her reading to me and encouraging me to learn, but I can’t remember her voice…More than once, I’ve longed for a memory of my mother that seems just beyond my grasp.”

In 1950, Mattie Cordell Ashe suffered a stroke while undergoing emergency surgery during her third pregnancy, and died three days later. She was 27, and her oldest son was just six. Arthur remembered his father coming home, grabbing him and his young brother, Johnnie, and crying, “This is all I’ve got left.”

Mattie’s death would have a profound effect on her oldest son’s life. He vividly remembered her wake in the family’s home, but chose not to attend her funeral for reasons he couldn’t quite explain. Eventually, his inability to connect to his feelings about her passing led him to speak to a psychiatrist, and try to uncover how her absence had influenced his personality. He came to believe that his famously detached nature may have been a product of losing his mother so early.

“I have never thought of myself as being cheated by her death,” he wrote, “but I am terribly, insistently, aware of an emptiness in my soul that only she could have filled.”

“Arthur wanted to be buried next to his mother,” Moutoussamy-Ashe says. “His father put flowers on his mother’s gravesite each week, and Arthur hoped the cemetery would be taken care of.”

Moutoussamy-Ashe would like to see Woodland’s chapel turned into a museum where the stories of those buried there can be told. She and Harris also believe the statue of Ashe on Monument Avenue should be moved there.

“It would give the statue and the cemetery more historical significance and context,” she says. “It would help shed a fuller light on Richmond’s history.”

“There’s a perfect site for it,” Harris says, “where four roads meet in a circle, where there were fountains once.”

“I know it can be done,” Harris says of moving the Ashe statue away from Monument Ave. “We just to have to get the city motivated.”

Jeanne Moutoussamy-Ashe's idea to resolve Arthur's statue struggle

Advertising

"Evergreen is the resting place for thousands of individuals who faced segregation, discrimination, and racial violence while contributing in important ways to the city’s—and the nation’s—vibrant social, political, intellectual, and religious life." (Quote and screenshot, enrichmond.org)

An effort has been made in recent years to uncover and shine a light on the city’s often-hidden, often-painful multicultural past and move beyond the cult of the Confederacy.

“It was quite a moment for this city to see the Jim Crow statues come down,” says Ana Edwards, who is chair of the Sacred Ground Historical Reclamation Project in Richmond. “Feelings were running high, but we finally reached this moment when they can’t be here anymore.”

According to Edwards, the Monument Avenue removals were a sign of a wider, ongoing, and welcome shift in perspective in the area.

“You have to appreciate the progress,” she says. “A few years ago, you couldn’t even say ‘racism’ or ‘white supremacy’ without people curling up into a ball. Now we’re finally starting to scrape everything away and tell the truth about our history. I think Americans like that, we like getting to the truth.”

Edwards has done her part to uncover some of that hidden history. Her organization has restored an African Burial Ground that had been covered by a parking lot, and is working to create a memorial park that will tell the story of the slave trade that went on in the city’s Shockoe Bottom neighborhood.

“When people think of the domestic slave trade, they might think of a single spot where there was an auction block,” Edwards says. “But this was an entire district that was devoted to that business, and its history has been completely invisible.”

Edwards agrees with Moutoussamy-Ashe that the Ashe statue doesn’t make sense where it is now.

“The idea was to honor him as a humanitarian, but unfortunately that was supplanted by the fight over whether it should go in a Confederate memorial,” she says. “It’s disconnected from its community.”

Regarding Monument Avenue, she and Moutoussamy-Ashe would both like to see the city take its time, think holistically, and not simply fill the empty plinths with new memorials to less-objectionable figures. Moutoussamy-Ashe believes the evicted Confederates should be housed in a museum.

“Like it or not,” she says, “they tell a history of this country.”

The statue of her husband also tells a history, one of achievement, progress, determination, and freedom, rather than subjugation. During his life, Arthur Ashe put Richmond, the African-American side of Richmond, on the global map in a way that few had before him. If Harris and Moutoussamy-Ashe have their way at Woodland Cemetery, his legacy and memory will continue to do the same.