Reading Julie Heldman’s new book—fittingly entitled Driven(A Daughter’s Odyssey)—I found myself thoroughly immersed in the story of her fascinating life. Navigating the pages of Heldman’s riveting autobiography/memoir, I wondered how she summoned the courage to write so forthrightly about the arduous and sometimes crippling campaign she has fought so valiantly against mental illness and the darkness of depression over the years. And yet, admirably, Heldman has confronted her lifelong struggles unswervingly.

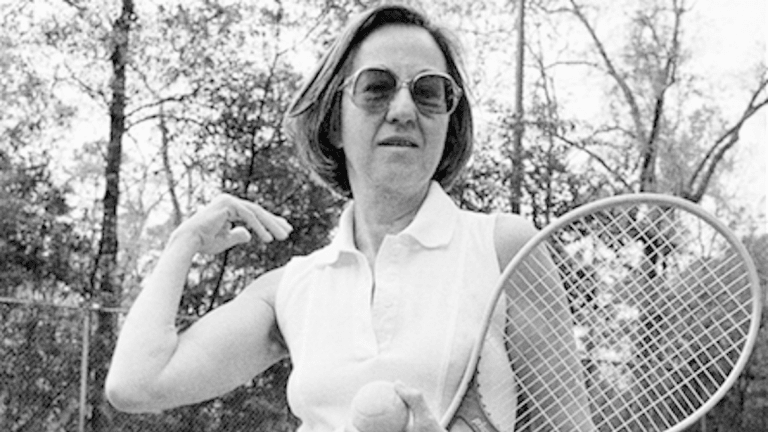

Current tennis followers and players are largely unaware of Heldman’s multi-faceted achievements on the court. She was a singularly crafty match player who broke into the American women’s Top 20 at No. 16 in 1961—when she was only 16. Later, she played on two victorious U.S. Fed Cup teams, climbed to No. 2 in her country, won the Italian Open in 1969, concluded two years stationed among the Top 5 in the world, and reached the semifinals of the 1974 US Open.

Heldman upended one luminous player after another, from Billie Jean King to Margaret Court, Chrissie Evert to Evonne Goolagong, Martina Navratilova to Virginia Wade. None of these prodigious champions could let their guard down against the guileful and unbending Heldman; they could beat her with their talent, but she could sometimes outfox them with her nonpareil brain. After she left her playing days behind her in 1975, Heldman, always a polished writer, shifted ably to the broadcast booth, establishing herself as a uniquely insightful analyst for NBC, CBS, HBO and other networks. Her powers of analysis were unassailable.

And yet, no matter how much she accomplished on and off the court, Heldman was overshadowed by her “indomitable” mother Gladys, a woman of extraordinary intelligence and inexhaustible ambition. Gladys founded WorldTennis in 1953, a magazine with the fitting motto: “written by and for the players.” WorldTennis was the centerpiece of the Heldman family, an all-consuming endeavor for Gladys, and a sibling of sorts for Julie and her sister Carrie. In Driven, she writes, “The magazine was the most demanding child in the family.”

In the tennis community, WorldTennis was a bible. Gladys—a modestly successful player who did not take up the game until she was 23, yet later competed in the U.S. National Championships— worked feverishly to make the magazine prominent and far reaching, and succeeded surpassingly. But as Julie grew up and found her own level of success, she had a mother who was unavailable in many ways.

Julie writes, “Mom’s ferocious WorldTennis workload turned her priorities upside down. She was too busy to play tennis, too busy to have a social life, too busy to be with her family. The magazine sucked out every ounce of her energy.”

Gladys kept Julie essentially on an island of her own.

Julie writes, “For three years, from the ages of four to nearly seven, when I should have been skipping rope and laughing hysterically with kids my own age, I spent the vast majority of my time alone. My isolation from outsiders was impenetrable.”