Novak Djokovic stands a US Open title away from becoming only the third man in tennis history to capture all four majors in a calendar year—the true Grand Slam. The other two are Rod Laver and Don Budge. Laver accomplished this feat twice, first in 1962 as an amateur, then in 1969 as a pro. Budge’s Slam came in 1938.

Thanks to the Laver Cup, ample YouTube clips, and tributes paid to Laver by the likes of Roger Federer, Pete Sampras, John McEnroe and Martina Navratilova, much is known about Laver’s genius—a dazzling lefthanded array of speeds and spins, angles and accuracy. The influence of The Rocket on the aforementioned quartet is vivid.

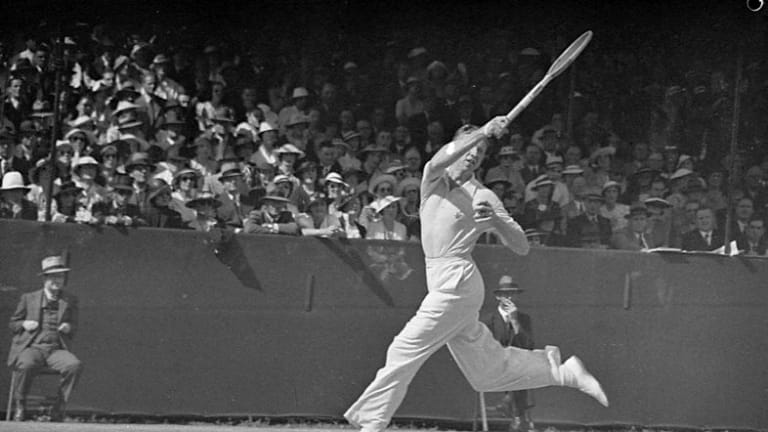

But when it comes to Djokovic, Budge is the more fitting stylistic ancestor. Start with a big picture look at how Budge shredded his opponents: a game fueled by relentlessly hard, penetrating groundstrokes. From “The Budge Style,” an article written by Julius Heldman in World Tennis magazine: “He never allowed his opponent to get his teeth into the match, and his overwhelming power was not subject to bad streaks. His unfortunate victim had the feeling of complete helplessness, for there was no way in which he could touch Don.”