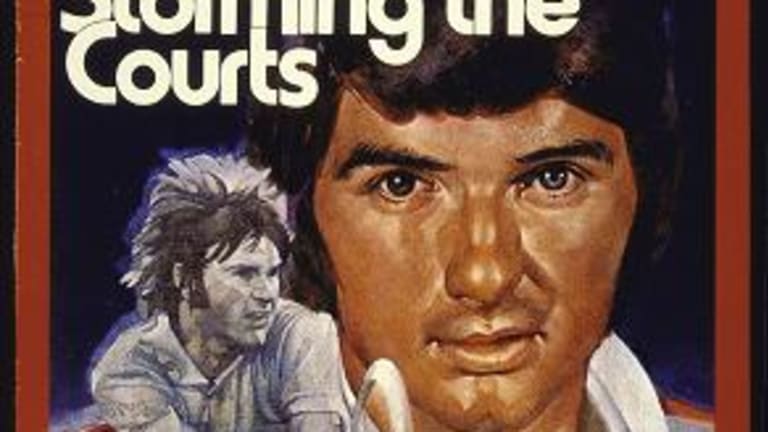

It was not long before tennis was on the cover of Time magazine, backed by a blow-out cover story on Connors. And if it's a bit of a stretch to say that the new era popped from Gloria Connors's womb, it's inarguable that she had spent the 20 or so years after Jimmy's birth shaping the slightly built, obedient, and terribly keen youngster into a tennis champion for a new era - one that would shatter all the codes and conventions and transform tennis players from clean-cut, generally understated, well-mannered sportsmen who proudly embraced an ethic based on equal parts sportsmanship and camaraderie into rock stars, with all the attendant virtues and vices.

Gloria could not possibly know about that, back when it all started. But she did know, or certainly sensed, that one way to become a great tennis player was to marry a very sound, consistent game to the heart of a remorseless assassin.

That her son was pre-disposed to this role was a blessing; that somehow her theories about these things would prove to be completely in step with the march of the times was something she could not.

Anyway, there always was more mystery about the Oedipal Frankenstein Gloria created than about the game Jimmy played. Frank Deford, an icon at Sports Illustrated, produced a masterpiece of amateur psychology in his classic, 1978 profile (it remains the definitive Connors piece): Raised by Women to Conquer Men. It was a story that also helped turn the flame wars between Connors and the press into a raging conflagration that never would be extinguished.

I escaped being tarred with the same brush as most pressmen thanks to Gloria Connors. Shortly after I wrote my first Connors story - a spirited defense of Connors and a paean to his combative spirit (I believe the headline - which I didn't write - was, Jimmy Connors: Is he the Greatest, Ever?) - I got a phone call shortly after the story ran. It was from Gloria. She wanted to thank me for writing so sympathetically about her boy. It probably helped my cause that Connors was, by then, getting caught in a classic pincer move of nearly military precision: The old guard resented Connors's punk personality and complete disregard for his elders (from Rosewall to the writers themselves); younger writers (my colleagues) found him corny, aggressive and no less contemptuous of them than of their journalistic heroes, like Deford.

I remember my own first impression of Connors because it was a simple one. He played Shock and Awe tennis like I had never witnessed before; he went after his opponents - and the ball - like a drunken cowboy in a bar fight. I was undecided about his personality, and probably more susceptible to the pack instinct that made the press corps determinedly anti-Connors. But my friend Liz Nevin, a girl I was then dating, absolutely, utterly loved Jimbo - almost as much as she would soon love Johnny Rotten. I reckon it was because neither of them gave a flying effword about anything. The Connors persona was sweetened for her by the fact that he was everything that tennis at that time still was not: outrageous, vulgar, gritty, square in that distinctly Amurican, Midwestern way that might make you think: Man, without tennis, this dude is just another bridge-painting loser in a Member's Only jacket. And she found him all the more appealing for it.

I was swayed, for sure, but if I had to pick a moment when the worm really turned, it was when Connors, refusing to apologize for some (probably) utterly mortifying act or remark that managed to offend everyone, made a comment that I am in the habit of quoting: "I do the crime, I do the time." Has a tennis player (or anyone else, for that matter?), faced with an opportunity to explain himself and thereby set into motion the redemption narrative (nowadays, we call it damage control), ever added defiance to his exquisitely tawdry conduct and come up with a more warped but authentic form of integrity? Not in my time. Connors's understudy, John McEnroe, sometimes tried, and one of the things he earned in so doing, besides our compassion, was the everlasting scorn of Connors. To say Connors had flaws is an understatement. He also had Wilanders.

But I'm getting away from Gloria here.

Gloria lived for Jimmy. She tracked his every move, read everything written about him, knew his game inside out and could get him sorted out when he was going through a rough patch like no other coach could. Early on, Jimmy confided to me that whenever he felt there was something wrong with his game, he would just call Gloria. I'll have to paraphrase him: Whatever it is, she fixes it in five minutes. In a comment at another post, Dunlop Maxply (Hank) noted that pundits never seemed to mention that Gloria Connors in her time was a very good tennis player (she was nationally ranked and, in a curious coincidence, briefly dated Chris Evert's father, Jimmy, when he was a player at Notre Dame). This probably was because the purely Oedipal narrative was far, far more seductive, it established a good base of operations for Connors's critics, and hey - the story line wasn't just more hooey dreamed up by some Greek playwright.

There certainly were flaws in the game Gloria implanted in Jimmy. He probably had the worst serve of any Open era icon - by far. As he hit it, his body would assume the shape of a capital "C", and you were inclined to turn away. Then there was that forehand, which Arthur Ashe attacked so mercilessly to forge his shining Warrior Moment with his shocking upset of Connors in the Wimbledon final of 1975. Jimmy's backswing was level, which made his flat forehand a very dangerous weapon. But when it was off, he almost appeared to swing high-to-low, which is suicidal. Because of his flat shot, he had trouble getting far enough under balls, especially off-speed balls, in no-man's land, and ended up smacking them into the netcord,or sailing them long for lack of arc.

Time-out for a Jimbo moment: After a particularly tough loss at Wimbledon one year, a reporter (think beer belly and mustard-stained necktie) kept badgering him about his high number of forehand errors. Jimmy finally colored - something Connors did often, for he was sensitive and somewhat insecure - and shot back, "Yeah? You want to go out and trade forehands with me?"

But say what you will about Gloria's role in the flawed game; in one department she was superb - she was the ultimate proponent of tough love, perhaps because her own life in the dreary town of East St. Louis, where Jimmy was born, was in some critical ways disappointing. She was estranged

from Jimmy's father, Jim, who worked as toll-booth manager on the Martin Luther King bridge over the Mississippi. Gloria lived modestly and trained Jimmy with the help of her own mother, Bertie Thompson (hence the plural "women" in the headline of the Deford piece). Fairly early in her life, Gloria became a realist, marbled with traces of bitterness that you would never in a million years catch her her owning up to. What other kind of person might be expected to pass on the wisdom: Do the crime and do the time? Gloria was a hard case.

Gloria taught Jimmy that if he didn't destroy his opponent - any and every opponent - he would be the one destroyed. That he never in his entire adult life held this against her - never uttered a word of ambivalence, regret, or self-pity, speaks volumes about his loyalty. His appreciation for what she did was never, ever undermined by grievances over what she didn't do, which, presumably, was nurture any aspect of his character other than his blood lust. Sigh. Then again, you could say he was genetically pre-disposed to having it that way.

I have my own theory on this: Connors was a sensitive, loyal, mother loving boy who absorbed the blows of reality, early and frequently, through tennis. He survived because he had a co-existing, equally deep toughness. And that sensitivity, occasionally expressed in an unexpected kind of tenderness later in Connors's life, I now realize, is what my friend Liz, a very bright woman, had detected in him.

Anyway, Gloria took Jimmy out to California to put the finishing touches on his game with the help of another hard case, a former barnstorming pro and master tactician from Equador, Pancho Segura. She and Jimmy shared an apartment in Los Angeles; I think she wanted to keep taut the Oedipal leash, and keep the sheltered, impressionable boy from losing his sense of purpose. Jimmy saw and grew envious of the lavish style in which many of his peers lived; he vowed to get some of that; he too would have a house with a pool ,in some place like Bel Air.

Segura believed in Connors' talent from the word go, even though Connors was a mere stripling at 5-10, 150 pounds, with arms like matchsticks. "Jeemee?" Segura would drawl. "Jeemee is a keeler. A keeler." Note that Segu didn't say Jimmy was a genius. Or an artist. Or a fleet, lithe, highly focused aggressive baseliner (that would be the Tennis Dictionary definition). Just a killer. Nothing more, but nothing less, either.

The two of them, Gloria and Segu, a pair of hard cases, kept pounding away at the boy with the sledgehammer, shaping him. What they were left with when they were done was still relatively small, but intensely compacted, free of all base or soft metals. This the unleashed upon the world.

I suppose you can't do that kind of work without also transforming yourself along the way as well, and by the time Jimmy began to tear apart opponents on the pro tour - something he did with eyes gleaming and blood-stained cheeks framing his smiling lips - Gloria seemed changed, too. Eventually, she moved back to Belleville, where she spent her time helping Jimmy with his affairs and teaching local kids the game, although it could not have been with the resolve and passion she had poured into Jimmy. I would get her on the phone, but her appearance at tournaments was a rarity. The hardness inside began to manifest itself on the outside. Gloria was tight-lipped and remote; even if you knew her, talking with her made you feel that you were trespassing, and you were never quite sure she was listening to what you were saying. It seemed that she had pretty much made her mind up, about everything, some time ago - and long before most of us do.

With her slack track suits, carapace of hair, pancake make-up, and a pair of eyes that glittered like navy-blue metal buttons on a uniform, she could easily be mistaken for one of those anonymous women who sits before a slot machine in Las Vegas, abstractedly pumping one quarter after another into the slot, cigarette dangling from the corner of her mouth, rhinestone-studded glasses on a string retainer.

It was, in fact, in Las Vegas that I collected my most enduring visual and most lasting impression of her. This was in 1975, shortly after Jimmy had beaten up on John Newcombe in the second of his infamous Heavyweight Champion of Tennis bouts (Rod Laver had been his first victim). These

exhibition matches had all the trappings and generated as much buzz as the event from which they stole the name. After counting coup on another Aussie legend, Jimmy held a small victory party in a bar in Caesar's Palace, and at one point I glanced over at the two of them. Gloria - she was much younger then, and a trim, attractive, obviously fit woman - was sitting in Jimmy's lap, gazing at him.

I suppose the look in her eyes might have been one of sheer pride. It could also have been admiration of what that thin, eager, hellbent little boy had become as a man. Perhaps it was thankfulness, for the triumph over Newcombe (with nearly half-a-million dollars at stake - a huge sum at the time) was a ticket to the Easy Street life they had never known. But in the end I thought it was just love.

And as a hard case, Gloria knew that you had to be very careful about where you looked for love, at least the kind that you could trust not to let you down.

RIP Gloria.