Pressure Points

Pancho Gonzales: The Man to Play for the Earth

By Jan 12, 2022Pressure Points

Monica Seles: The Woman to Play for the Earth

By Jan 12, 2022Pressure Points

Pressure Points: Inside the toughest matches for Serena, Federer, Nadal, Osaka and Djokovic

By Jan 12, 2022ATP Munich, Germany

Ben Shelton and Francisco Cerundolo join Alexander Zverev in Munich semifinals

By Apr 18, 2025Social

Carlos Alcaraz offers support to Sara Sorribes Tormo after she announces break from tennis

By Apr 18, 2025ATP Munich, Germany

Alexander Zverev needed a win like his 'close one' against Tallon Griekspoor in Munich

By Apr 18, 2025ATP Barcelona, Spain

Holger Rune ousts Casper Ruud in Barcelona, thanks social media for making H2H a 'big deal'

By Apr 18, 2025ATP Barcelona, Spain

Play suspended in Barcelona when the wrong racquet gets taken for stringing

By Apr 17, 2025Pop Culture

Serena Williams named to Time's 100 most influential people ... and Coco Gauff approves!

By Apr 17, 2025WTA Stuttgart, Germany

Jelena Ostapenko tops Emma Navarro for Iga Swiatek Stuttgart clash; Coco Gauff, Jessica Pegula roll

By Apr 17, 2025Pressure Points

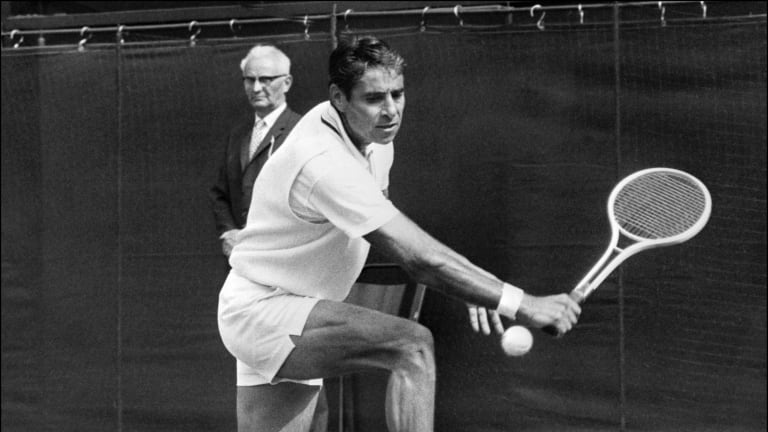

Pancho Gonzales: The Man to Play for the Earth

In part one of an out-of-this-world, pressure-packed tale—one man and one woman to play for the fate of the planet—an American legend is called up to serve.

Published Jan 12, 2022

Advertising

Advertising

Pancho Gonzales was inducted into the International Tennis Hall of Fame in 1968.

© AFP via Getty Images

Advertising

Advertising

Gonzales won 14 major singles titles, including two U.S. National Singles Championships in 1948 and 1949.

© AFP via Getty Images