It occurred to me, as I started to write this post, that the most welcoming landscapes in the two places where I’ve lived have been graveyards. Williamsport, Pa., where I grew up, is overlooked by picturesque Wildwood cemetery, which winds around the steep wooded hills on the north side of town. At the center of Brooklyn, N.Y., where I live now, is one of America's most famous cemeteries, Green-Wood, home to local legends as diverse as Leonard Bernstein, F.A.O. Schwartz, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Crazy Joe Gallo, and Boss Tweed. I love both of these Woods, Green and Wild. They seem like luxuries of public life, communal spaces that are spiritual rather than commercial. Like church, they're symbols of the afterlife, but without the guilt or the singing or the kneeling. Just the fact that we honor the dead by marking down their names and giving them a piece of real estate in perpetuity is proof to me that there's something good inside of us.

Both of these cemeteries roll over hills and under trees, and their gravesites are placed along crisscrossing walkways that make them feel like bucolic bedroom communities. Death in the U.S. must be kind of like moving to the ’burbs. Green-Wood is the only place I’ve found in New York where you can hear almost nothing at all. The only sound, a distant ambient hum, comes from the airplanes that fly across Brooklyn to La Guardia.

If you’ve been to, or seen photos of, a Paris cemetery, you know that they’re more urban and jumbled than they are bucolic. Flat stones and taller monuments are jammed together, with only the thinnest space between each of them, like brownstones in Brooklyn or row houses in Philly. Instead of vast lawns and curving lanes, you walk along tree-lined, asphalt boulevards that are named the same way that the real streets of Paris are named. The dead don’t leave town here. They remain committed urbanites, city slickers forever. One Parisian cemetery resident, Charles Pigeon, and his family haven’t just stayed in town. They've stayed in bed.

A comfortable spring breeze hit my face when I walked into Montparnasse Cemetery on Saturday morning. Just around the corner from my hotel, it was the most convenient tourist site for someone working 10 hours a day. But coming here was immediately a pleasure. Like my old graveyard haunts, once you’re safely inside its stone walls, Montparnasse wards off the harsher sounds of the city. The buzz of Paris’s motorbikes and the sirens of its police cars and ambulances are frozen out; they seem to come from far away. By the time you’ve reached the cemetery’s center they’ve vanished, as have the normal frantic rhythms of the city. You can walk slowly here.

Paris’s cemeteries house even more of its most famous citizens than Green-Wood does Brooklyn’s. Montparnasse, which was laid out in 1824, is not the home of Jim Morrison; he's at Père Lachaise, an even bigger and more tightly packed site a little farther from the city’s center. But Montparnasse does have a shrine to Paris’s own deceased 60s icon of music and decadence, Serge Gainsbourg. His site is on a prime piece of real estate near the middle of the cemetery—I wonder who they booted to make room for Serge?—and covered with photos and flowers. It’s impossible to miss.

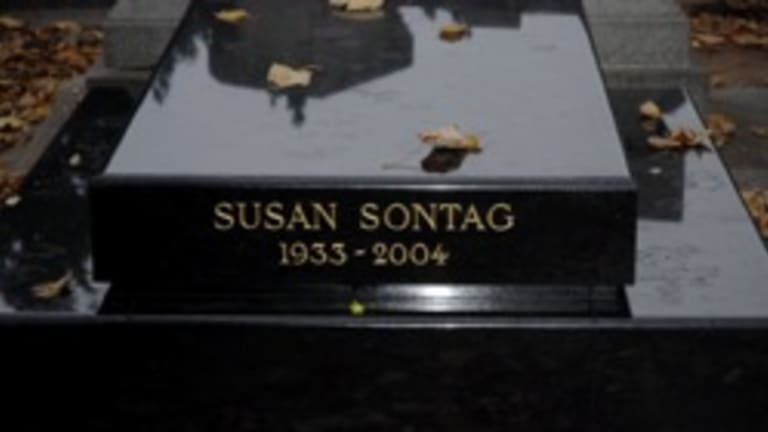

That’s not true of most of the notable graves here, even when the people in them are infinitely more worthy of attention. Befitting this bohemian neighborhood, the cemetery specializes in allowing writers and artists to, hopefully, find eternal rest. Samuel Beckett is here, but I couldn’t find him. While I was poking around on his block, though, I accidentally ran across Susan Sontag’s grave. “The Susan Sontag?” was my first disbelieving thought; the cemetery doesn’t even list her on their map. On Saturday morning the flat black stone that has her name, the years of her life, and nothing else engraved on it looked lonely compared to Serge’s. There was nothing on top of Sontag’s but a stray metro ticket and some sticky leaves that had dropped from the tree above.

I wrote the other day that finding yourself alone with a famous landmark is a strange and awesome sensation. The same is true when you’re alone at a famous person’s gravesite. But while it’s a thrill—at that moment, you’re closer to that person, that figure, than anyone else—it’s also humbling and plainly sad. I liked what I’d read by Sontag, but she wasn’t a literary hero of mine. If I’d thought about it, I would have remembered that she’d died a few years ago, but seeing her name still came as a melancholy shock. What was this New York girl doing here by herself, so far from home?