Player boycott or not, Jan Kodes' 1973 Wimbledon triumph was for real

By Steve Flink Jul 08, 2020Darren Cahill: Jannik Sinner watches more Carlos Alcaraz matches than he does with any other player

By TENNIS.com Jul 14, 2025Jannik Sinner reignites Carlos Alcaraz rivalry with Wimbledon victory

By Pete Bodo Jul 14, 2025Jannik Sinner reversed his usual pattern against Carlos Alcaraz. It won him Wimbledon

By Steve Tignor Jul 14, 2025Veronika Kudermetova and Elise Mertens win women's doubles title at Wimbledon

By Associated Press Jul 13, 2025Joy to the World: What Carlos Alcaraz has, and what we are enjoying

By Peter Bodo Jul 13, 2025Iga Swiatek keeps surprising herself after Wimbledon title caps "surreal" turnaround on grass

By Steve Tignor Jul 12, 2025Iga Swiatek wins first Wimbledon, sixth Grand Slam title with 6-0, 6-0 rout of Amanda Anisimova

By Ed McGrogan Jul 12, 2025Wimbledon men's final preview: Will Carlos Alcaraz, Jannik Sinner share another epic?

By Steve Tignor Jul 12, 2025Julian Cash, Lloyd Glasspool become first all-British pair to win Wimbledon men's doubles title since 1936

By Associated Press Jul 12, 2025Player boycott or not, Jan Kodes' 1973 Wimbledon triumph was for real

No less than 13 of the original 16 seeds chose to skip the tournament on behalf of Yugoslavian Nikki Pilic, who had been suspended by his federation.

Published Jul 08, 2020

Advertising

Longtime tennis followers are deeply saddened by the cancelation of Wimbledon this year, equating it in some ways with a death in the family. The last time the world’s preeminent tournament was not held occurred from 1940-45 during World War II.

We are missing it sorely right now. But purists readily recollect 1973, when the ATP boycotted on behalf of their constituent Nikki Pilic, a left-hander from Yugoslavia who had been suspended by his federation.

Nearly all of the sport’s leading players sacrificed their personal goals for a larger cause, including defending champion Stan Smith, 1970-71 winner John Newcombe, Ken Rosewall, Arthur Ashe, Roy Emerson and other prominent figures. They chose to skip the game’s showcase event. No less than 13 of the original 16 seeds were part of the boycott.

But not Jan Kodes. He joined young players and non-ATP members like 1973 French Open champion Ilie Nastase, Jimmy Connors, and Bjorn Borg in a diminished field, but the fact remained that Kodes—victorious at Roland Garros in 1970 and 1971—still claimed the most prestigious crown of his Hall of Fame career.

Seeded No. 2 that year (he was originally at No. 15 before so many top players withdrew), Kodes did not believe that the boycott was justified.

“I was not a member of ATP. Pilic was suspended by the ITF,” he told me a few weeks ago. “The ATP was going against the ITF. I was not okay [with the Pilic suspension]. The problem was that the Yugoslav Tennis Federation made the suspension. But Wimbledon was organized by the All England Club. They had nothing to do with Pilic in this case. So I think the ATP's decision to boycott was not right.”

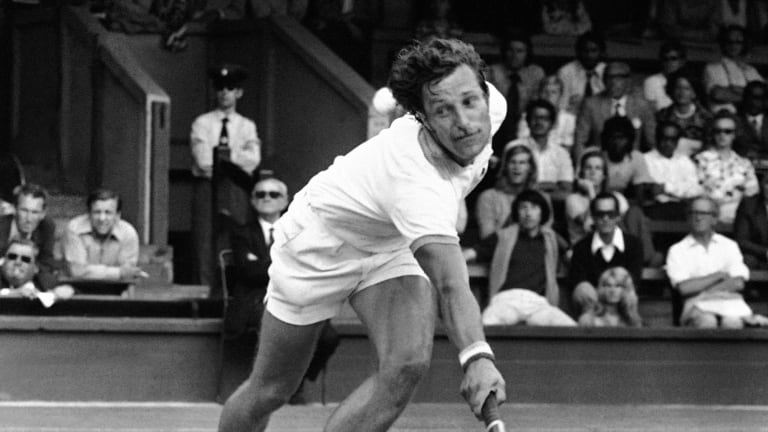

Player boycott or not, Jan Kodes' 1973 Wimbledon triumph was for real

© Getty Images

Advertising

The former world No. 5 en route to his 1973 victory at the All England Club. (Getty Images)

Asked if it crossed his mind that the absence of so many top of the line players gave him a much better chance to win Wimbledon, Kodes replies unhesitatingly, “No. I didn’t think about that at all. There were all of these other guys in the tournament that I knew were good enough.”

Kodes did not commence his quest for the title auspiciously, dropping the first set in the opening round against Ken-Ichi Hirai. But he was not unduly concerned.

“I was playing on Court 1,” he recalls, “The court was very slippery and Court 1 was the fastest court in all of the club. The guy played pretty well in the first set but I was not worrying. I did not think I was going to lose this match and I ended up winning in four sets.”

Kodes took his next two matches comfortably but then found himself up against a wily grass-court player in the round of 16. The Indian stylist Jaidip Mukerjea tested Kodes considerably.

“He was tough,” says Kodes. “India was a grass-court country. Mukerjea returned very well. He made me work hard. He could come in and he also lobbed well. He had experience. I was a little afraid before I played him.”

After capturing that contest in four sets, Kodes moved on to a quarterfinal appointment back on Court 1 with another Indian. Vijay Amritraj was 19, immensely gifted, a classical attacking player, and entirely at ease on grass courts. He pushed Kodes to the brink of defeat.

As Kodes recollects, “Vijay was a very promising player who was hitting the ball very early and going mainly down the line. He played much better than I thought he would. He did not have much experience at that time. In the fifth set we both kept holding our serves. It was 5-4 for him with me serving. I was down 15-30. I had to play a half volley drop shot but he reached it and put a lob over me. I ran back and lobbed very high. He was against the sun and missed and overhead to make it 30-30. I then held my serve, broke Vijay in the next game and won the match, 7-5, in the fifth set.”

Kodes was living dangerously but competing with the temerity of a champion. In the semifinals, he collided with veteran British left-hander and perennial Wimbledon contender Roger Taylor, twice a semifinalist in the past. Once more, Kodes was taken down to the wire by a daunting adversary who was tailor made for the grass. The No. 3 seed Taylor had toppled Borg in five tumultuous sets.

Not only did Kodes have to overcome a formidable adversary in Taylor, but he also had to deal with a Centre Court audience yearning for a local favorite to succeed.

As Kodes reflects, “Roger was a big server. It was not easy to break him. It was a high quality match and I have a feeling I won it because physically I was physically I was a bit stronger than him. There was a rain break when I was down 4-5 in the fifth. Captain Gibson who was the referee stopped the match then, which I did not think was really fair. But I could not do anything about it.”

Player boycott or not, Jan Kodes' 1973 Wimbledon triumph was for real

© AFP via Getty Images

Advertising

Kodes at the 2015 Wimbledon Championships. (Getty Images)

After the delay, Kodes was calm and deliberate. He says, “I played solid when I came back to serve at 4-5. I decided to not take any risks and just keep the ball in the court and make him try to pass me. I had talked to Jaroslav Drobny before the match. He won Wimbledon in 1954. He was also a left-hander like Roger. He said I should not play to Roger’s forehand because Roger could use his big reach and pass me on the run. Drobny said I should keep going to his backhand so I did that.”

Kodes won that one, 7-5, in the fifth as well, so he was right where he wanted to be, one match away from a career-defining title, and understood the circumstances much better than his final opponent, Alex Metreveli. However, Kodes had not fared well in the past against the fourth-seeded Metreveli, who had ousted Connors in the quarterfinals.

“My record against Metreveli was something like 1-5 going back to the Galea Cup juniors,” he points out. “I had lost to Metreveli at Wimbledon in 1970 after I won my first French Open. He beat me on Court 2 in five sets. That was the reason I was not seeded the next year at Forest Hills for the US Open because the seeding committee thought I could not play well on grass, but I beat [top seeded] John Newcombe in the first round and made it to the final.”

Be that as it may, Kodes had a very professional outlook as he approached his duel with Metreveli: Be wary of Metreveli’s grass-court acumen but don’t forget you are far more familiar with the treacherous territory of competing for prestigious prizes. For Kodes, this was his fourth appearance in a major final while it was a maiden voyage for Metreveli.

“I knew his game and he knew mine,” Kodes remembers. “I was afraid of him because he was better than everybody thought he was, an all-around player who could make passing shots, drop shots and lobs. What I was counting on was that because I had played three major finals and he had played none, he might be nervous from the beginning, and that is exactly what happened. He started badly. He was double faulting and missing returns and passing shots. My tactics were not to miss and just keep the ball in the court without trying something special. I also served into his body a lot.”

A decidedly more composed Kodes secured the first set swiftly, 6-1. The key to the outcome was the second set, which Metreveli took into a tie-break at 8-8 as it was played in those days at Wimbledon. Kodes was too good in that sequence. He swept to a 6-1, 9-8 (5), 6-3 victory for his highest honor.

Even 47 years after the fact, Kodes speaks with remarkable clarity about the importance of winning that Wimbledon final.

“It was very important,” Kodes says. “I had to win that match. I wanted to be known as an all-court, all-surface player. Also, I had the feeling playing Metreveli in the final that I had a hell of a chance to win. Me playing him in the final was like Newcombe playing Wilhelm Bungert in the 1967 final or Laver playing Marty Mulligan in 1962. You have to take advantage of your opportunities.”

Player boycott or not, Jan Kodes' 1973 Wimbledon triumph was for real

© AP

Advertising

The Czech was seeded No. 2 at the 1973 Championships. (AP Photo)

For Kodes, it had been a process of developing the necessary grass-court skills over a two year period that led him to Wimbledon glory. His exploits at the 1971 US Open were pivotal.

“That was the turning point in my mind,” Kodes asserts. “I showed that I was able to play on grass at Forest Hills. Everybody had been saying that I am only a clay-courter. But I beat guys like Bob Lutz and Frank Froehling after the Newcombe win and then beat Arthur Ashe in five sets. I lost to Stan in the final but got a lot of confidence from that tournament.”

The next year at Wimbledon, Kodes took another significant step, reaching the penultimate round.

“I was not a big server or a guy hitting the ball a hundred miles an hour,” he says. “I relied on my second serve placement and tried to mix up my serve. I played a little bit on grass the way Edberg did later on, coming in close behind the serve, especially on the second serve. My strategy was that I was going to have to play the volley, making a first volley, a second volley and then an overhead. I also found out I was very good with the drop volley. I made many of them against Newcombe at the '71 Open.”

Kodes reached a second US Open final later in the summer of 1973 after his Wimbledon triumph. This time, he stopped Smith in the semifinals from match point down in five sets before losing in five to Newcombe after leading two sets to one.

He muses, “I should have won that match against John. In my semifinal with Stan, there was a bad call against me in the second set tiebreaker. Instead of two sets for me, it was one set all. Later, I thought I could have won in three sets instead of five and I would have had more energy for the final.”

But in his mind, Kodes was vying for more than just the US Open title against Newcombe.

“I had a feeling when I was playing the match that I was playing for No. 1 in the world, “he says. “But because I lost I think I was No. 3 or 4 after the US Open. If I had won both the US Open and Wimbledon, I thought I would be ranked No. 1 in the world and would deserve it. 1973 was actually my season that I should be No. 1.”

Yet Kodes need not be remorseful nor apologetic about his three majors, enduring consistency and multitude of successes. The crowning moment in a stellar career was, of course, ruling on the lawns of Wimbledon.

As he says, “Wimbledon psychologically is more important than my two French Opens, even if it is much harder physically to win in Paris. Wimbledon is the most important tennis tournament in the world by history.”

Player boycott or not, Jan Kodes' 1973 Wimbledon triumph was for real