Roger Federer’s longstanding Aussie affinity tells a storied tale

By Dec 29, 2020Social

Roger Federer and Caroline Wozniacki step out at the Masters: “So much tradition”

By Apr 13, 2025ATP Monte Carlo, Monaco

Richard Gasquet given Monte Carlo wild card 20 years after breakthrough win over Roger Federer

By Apr 03, 2025Second Serve

Wolfgang Puck: The biggest tennis fan in the kitchen?

By Mar 12, 2025Pop Culture

Serena Williams, Roger Federer, Aryna Sabalenka and pickleball all featured during Super Bowl LIX

By Feb 13, 2025Lifestyle

Roger Federer’s Wimbledon-winning racquet sells for more than $100,000 in tennis auction

By Feb 10, 2025Pop Culture

Roger Federer explains tennis scoring, On logo to Elmo in Super Bowl ad

By Feb 10, 2025Lifestyle

Roger Federer’s Wimbledon winning racquet currently up for auction

By Jan 28, 2025Australian Open

Henry Bernet, Australian Open junior champion, takes inspiration from fellow countrymen Roger Federer and Stan Wawrinka

By Jan 25, 2025Style Points

The best tennis fashion moments of 2024: Federer & Nadal for Louis Vuitton, Kostyuk's viral Wimbledon dress and more

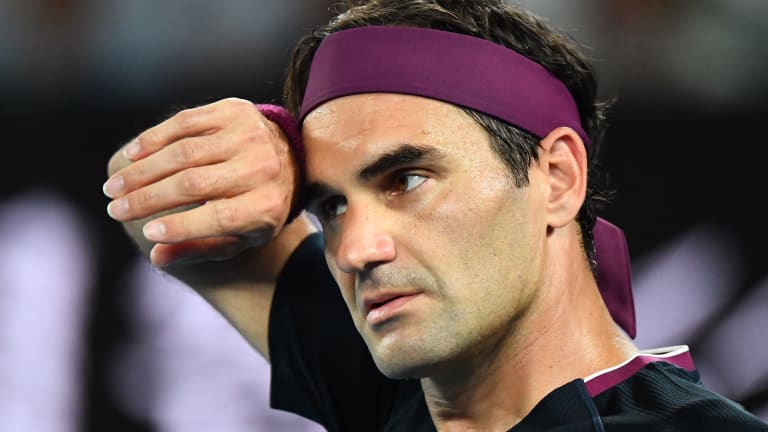

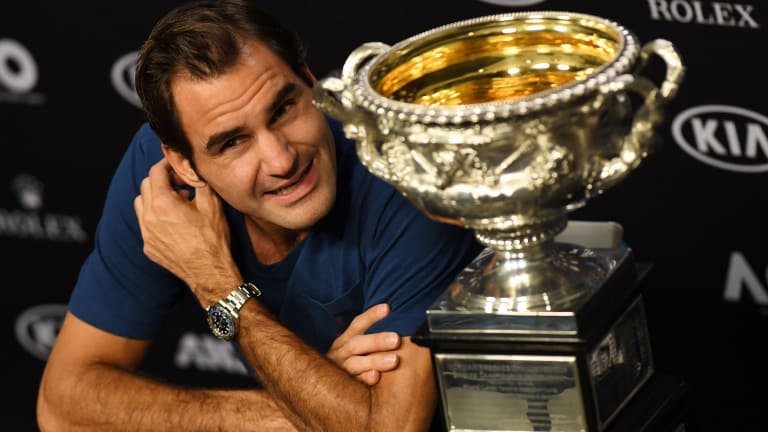

By Dec 14, 2024Roger Federer’s longstanding Aussie affinity tells a storied tale

Melbourne is arguably the 39-year-old's wellspring: the people, places and moments that greatly shaped the king.

Published Dec 29, 2020

Advertising

Roger Federer’s longstanding Aussie affinity tells a storied tale

© AFP via Getty Images

Advertising

Roger Federer’s longstanding Aussie affinity tells a storied tale

© 2006 Getty Images

Advertising

Roger Federer’s longstanding Aussie affinity tells a storied tale

© AFP via Getty Images