Wimbledon

TBT, 1969 Wimbledon: The lion inside Pancho Gonzales comes out

By Jun 25, 2020Wimbledon

Wimbledon to replace line judges with electronic line calling from 2025

By Oct 09, 2024Wimbledon

The amazing journey of Henry Patten from IBM data logger to Wimbledon doubles champion

By Jul 16, 2024Wimbledon

Hsieh Su-Wei, Jan Zielinski win mixed doubles title at Wimbledon

By Jul 15, 2024Wimbledon

Why Wimbledon Endures

By Jul 15, 2024Wimbledon

Novak Djokovic seeks 2024 answers for Alcaraz and Sinner after great effort: 4 ATP Wimbledon takeaways

By Jul 14, 2024Wimbledon

Carlos Alcaraz is a champion establishing how high he will climb with latest Wimbledon title

By Jul 14, 2024Wimbledon

Nicolai Budkov Kjaer makes history in winning junior boys' Wimbledon title; Renata Jamrichova wins girls' title

By Jul 14, 2024Wimbledon

Carlos Alcaraz beats Novak Djokovic again in Wimbledon final for fourth Grand Slam title

By Jul 14, 2024Wimbledon

For Jasmine Paolini, Barbora Krejcikova was one forehand and one serve too good in the Wimbledon final

By Jul 13, 2024Wimbledon

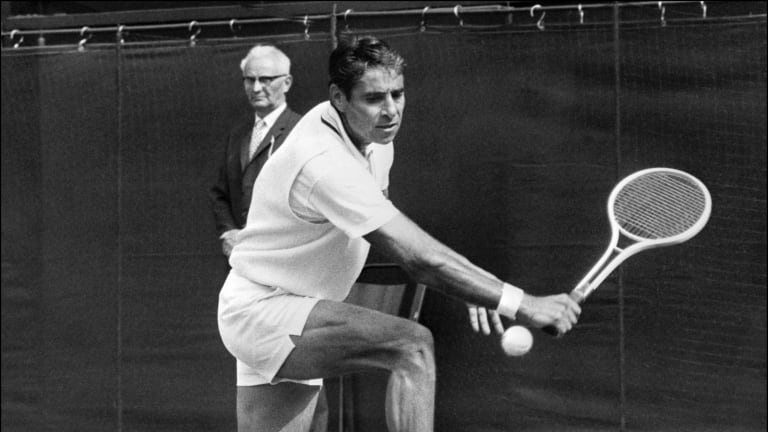

TBT, 1969 Wimbledon: The lion inside Pancho Gonzales comes out

The roots of this Centre Court moment went back more than 20 years. At the end of 1949, Gonzales had turned pro—and thus been banned from such prestigious events, forcing him to play in dim-lit arenas, on surfaces that ranged from slick wood to cow dung.

Published Jun 25, 2020

Advertising

TBT, 1969 Wimbledon: The lion inside Pancho Gonzales comes out

© AFP via Getty Images

Advertising

TBT, 1969 Wimbledon: The lion inside Pancho Gonzales comes out