Editor's Note: On Friday, after years of failing health, Bud Collins died in his Brookline home at age 86. Last November, as part of TENNIS Magazine's annual Heroes issue, Steve Tignor wrote about the legendary tennis writer, broadcaster and personality.

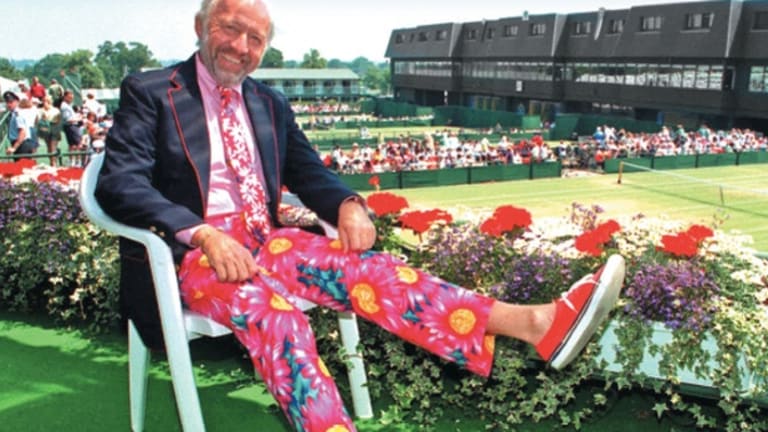

It was entirely fitting that the U.S. Open renamed its media center in honor of Bud Collins this year. The famously colorful writer—in both word and garb—covered the first Open in 1968, and every one after until 2013. During those years, Collins made himself very much at home in the press room. For many in the tennis media, the tournament didn’t begin until we’d seen a brightly hued Bud padding around in his socks and greeting us, in that richly good-humored voice we grew up listening to on TV, with a wide smile and a word of praise for a story we’d recently written.

The Open’s selection process couldn’t have taken long, because there really was no other choice. Collins, who turned 86 this summer, isn’t just a tennis reporter; he was the first U.S. sportswriter to consider the game important enough to make it his specialty. And he isn’t just a tennis historian; by bearing witness to every significant event of the last five decades, Collins was instrumental in creating and composing the lore of the Open era. It’s not too much of an exaggeration to say that without Bud, there might not even be a tennis history.

Collins began narrating that history in the 1950s, when he convinced his skeptical editors at the Boston Herald to let him cover what he called the “secret sport,” which was then kept largely hidden behind country-club walls.

“To me,” Collins later wrote, “tennis was a wonderful game that could win a larger following if the press and TV—and the game’s leaders—would give it a more thorough chance.”

Over the next half century, Collins did more than his share to give it that chance. Yet change came slowly: In 1968, when Wimbledon held its first open championship, he was the only U.S. journalist to travel to London to cover it. With Collins's help, that milestone tournament helped set off the following decade’s tennis boom, a phenomenon that would find a ready voice in the silver-tongued scribe. By the early ’70s, Collins was in the CBS booth at the U.S. Open, and in 1979 he returned to London not as a lone-wolf reporter, but as the color commentator for NBC’s first serving of Breakfast at Wimbledon.