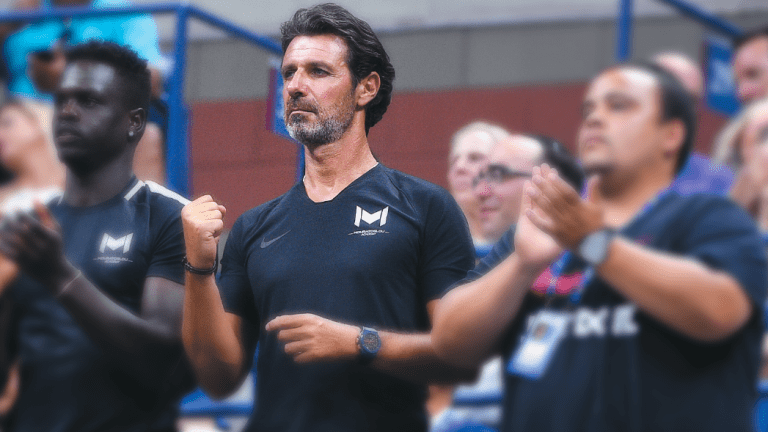

Garbine Muguruza and her coach, Sam Sumyk, have a testy exchange at the WTA Elite Trophy in Zhuhai:

The Coaching Question: What is the future of on-court coaching?

By Steve Tignor Jan 11, 2019Ranking Reaction

Aryna Sabalenka surpasses 10,000 ranking points for the first time, joins exclusive list

By John Berkok Apr 02, 2025Miami, USA

Novak Djokovic lights up Miami Open as Serena Williams, Juan Martin del Potro watch on

By TENNIS.com Mar 26, 2025Stat of the Day

Mirra Andreeva becomes second-youngest woman to defeat No. 1 and No. 2 at the same tournament

By John Berkok Mar 16, 2025Lifestyle

The Tennis Traveler: How and where the pros prepared for Tennis Paradise at the BNP Paribas Open

By Liya Davidov Mar 06, 2025Social

Spotted: Meghan Markle’s daughter plays Candy Land with ‘auntie’ Serena Williams

By Liya Davidov Mar 04, 2025The Business of Tennis

Serena Williams joins ownership group of Toronto Tempo WNBA team

By Baseline Staff Mar 03, 2025Pop Culture

David Beckham gifts Serena Williams Inter Miami CF jersey at 2025 season opener

By Baseline Staff Feb 26, 2025Pop Culture

Serena Williams, Roger Federer, Aryna Sabalenka and pickleball all featured during Super Bowl LIX

By Liya Davidov Feb 13, 2025Pop Culture

Serena Williams performs with Kendrick Lamar at Super Bowl LIX Halftime Show

By David Kane Feb 10, 2025The Coaching Question: What is the future of on-court coaching?

Published Jan 11, 2019

Advertising

The Coaching Question: What is the future of on-court coaching?

Call it the hand signal that rocked the world.

It was the briefest and most innocuous of gestures. Patrick Mouratoglou, coach of Serena Williams, had sat in Arthur Ashe Stadium and watched his player lose the first set of the 2018 US Open final to Naomi Osaka. So he did what any decent tennis coach would do: he put his hands in front of him and pushed them forward a few inches. It was his way of telling Serena to move up in the court and take charge of the points.

The communication was over in a second, but that was enough time for chair umpire Carlos Ramos to spot it. Ramos handed Williams a code violation for illegal coaching, and the rest of the night—unfortunately—is tennis history.

After Serena’s defeat and the torrential downpour of boos that came with it, Mouratoglou admitted that he had coached her. But instead of saying that he wouldn’t do it again, the Frenchman took the opportunity to assert that tennis’ age-old rule against in-match coaching needed to change. He went so far as to cast the debate as a “confrontation between two ways of thinking: the conservative, traditionalist way, and the modern, progressive way.”

“I have never understood why tennis is just about the only sport in which coaching during matches is not allowed,” Mouratoglou said.

“Coaching is a vital component of any sporting performance. Yet banning it almost makes it look as if it had to be hidden, as if it was shameful. Authorizing coaching in competition and actually staging it so that the viewers can enjoy it as a show would ensure that it remains pivotal in the sport.”

Advertising

The Coaching Question: What is the future of on-court coaching?

While Mouratoglou’s plea was construed by many as self-serving, he was also articulating a philosophical schism that has divided the sport for the last decade. On one side of that divide are, as Mouratoglou says, the traditionalists. They emphasize that tennis is a one-on-one sport, in which players must solve their own problems—mentally, physically, emotionally, tactically—once they step on court.

On the other side of that divide is a smaller group that believes on-court coaching adds drama and personality to TV broadcasts. They say that the pros are illegally coached from their player boxes anyway, so why not showcase it and derive some entertainment value from it?

Tennis being a traditionalist’s sport, those against on-court coaching outnumber those in favor of it. Yet that didn’t stop the WTA, in 2008, from allowing it at tour events. For the last decade, players have been permitted to request one visit from their coach per set. Labeled an “experiment,” the move was designed with television in mind; coaches are required to wear microphones during their visits.

The rule change was greeted, predictably, with disgust, and even after 10 years WTA coaches and players continue to express reservations about it. But if the experiment hasn’t been accepted, it has accomplished what it was intended to accomplish.

On-court coaching has added an extra dash of personality—a discussable moment—to the WTA. Whether they’re inspirational or embarrassing, the sideline visits are among the most talked-about aspects of any match, and among the most widely shared on social media. We’ve seen jarringly testy exchanges between Garbine Muguruza and Sam Sumyk; soul-searching conversations between Simona Halep and Darren Cahill; and rapid-fire monologues by Piotr Wozniacki, as his daughter Caroline stares straight ahead in stone-faced silence. For 90 seconds, fans can glimpse how players and coaches relate to each other under stressful circumstances.

Advertising

The Coaching Question: What is the future of on-court coaching?

© Koji Watanabe

While WTA CEO Steve Simon acknowledges that on-court coaching has its critics, he remains committed to the idea.

“Coaching, from my perspective, is here to stay as a part of the WTA,” Simon said at the end of the 2018 season. “Coaching is a part of sport. It’s an integral part of the sport of tennis. We can’t say that coaching doesn’t happen and just look the other way. I think we have to support it, and support it in a responsible way.”

Rather than curtailing coaching, Simon would like to see it expanded.

“What I’m hoping for is that as coaching is utilized throughout the sport,” Simon said, “there is an alignment with respect to when coaching is allowed, that it’s at least consistent across the board.”

That might sound like a reasonable enough request, but until this year, the rest of the sport didn’t seem likely to come around to Simon’s way of thinking. Most media, fans and ex-players have long viewed on-court coaching as a betrayal of the game’s individualist ethos, and neither the ATP nor the Grand Slams have seriously considered allowing it. Until now, that is. In 2017, the US Open began allowing sideline coaching visits during qualifying, and the calamitous end to last year’s women’s final in Queens may finally have made the sport’s ultimate traditionalist institution, Wimbledon, think twice about the issue.

“People might say, ‘Shall we all vote for coaching, it’s good for the sport’,” Wimbledon chairman Philip Brook told the BBC after last year’s US Open. “We will say no, but if the rest of the sport say we want to do it, and there are good reasons, then maybe Wimbledon should fit in.

“What we would like to learn from those who have conducted trials is: persuade us why it’s a good idea.”

Advertising

The Coaching Question: What is the future of on-court coaching?

© 2018 Getty Images

Is it worth trying to persuade Brook and his fellow Wimbledon officials? Has the time come to institute on-court coaching throughout the game?

We can start by saying that the traditionalists overstate their case when they maintain that, at its essence, tennis is purely a one-on-one sport. On-court coaching has been a feature of the game at multiple levels for decades; it’s allowed in high school, college and USTA league matches. At the professional level, it remains an integral part of Davis Cup and Fed Cup. For much of the sport’s history, Davis Cup was the most prestigious men’s event, more important to the players than Wimbledon or any of the Grand Slam tournaments. It’s hard to claim that, because there is a team captain on the court who can give advice during play, Davis Cup somehow doesn’t qualify as tennis.

Traditionalists have also alleged that allowing on-court coaching during WTA matches makes female players “look weak.” By that logic, Tom Brady and Stephen Curry look weak when they run plays designed by their coaches, Tiger Woods looks weak when he consults with his caddy and Rafael Nadal looks weak when he listens to his Davis Cup captain. All athletes, men and women, are coached.

Another line of argument asserts that on-court coaching shouldn’t be allowed because it isn’t fair to players who don’t have the resources to hire a top coach. But that type of inequality is already built into pro tennis. The highest earners have the best and most expensive support teams assisting them all day, every day. The only time pros aren’t being coached is when they’re playing a match.

Finally, some worry that WTA players will come to rely too heavily on their coaches during tour events, and then flounder when they can’t talk to them at the majors. This hasn’t proven to be the case. All of last year’s Grand Slam singles champions—Wozniacki, Halep, Angelique Kerber and Osaka—regularly call for their coaches when they’re playing WTA tournaments.

And yet, anyone who has ever played a tennis match and felt the thrill and intensity of its hand-to-hand combat, as well as the satisfaction that comes with winning that exchange, will know that the traditionalists have a point. Former world No. 1 Tracy Austin recently spelled it out with particular force.

“I think it should be taken out all together,” Austin says of the WTA’s on-court coaching rule. “I think that it should be mano a mano, whatever tools I have—whether it’s emotionally or technically or tennis-wise—versus yours.

“I hate the fact that someone can come on court and help my opponent if they’re lacking in that mental strength, or to keep that even-keel emotionally. They can change the course of a match.”

In other words, the uniquely tough and thoroughgoing test that tennis sets before its players—that they’re personally responsible for whatever happens once they walk on court—is what elevates this sport above others.

Advertising

The Coaching Question: What is the future of on-court coaching?

© AFP/Getty Images

Maybe, in the case of coaching, tennis’ divided nature is a blessing. We can accept that the game takes different forms—team events, tour events, school events, league play, Grand Slams—and different attitudes toward coaching are appropriate for each.

“I think it’s great for TV, and it’s great for the game,” Chris Evert recently said of the WTA’s on-court coaching rule. “With Grand Slams, I’m a little more reserved about that, because I do feel that you have to problem-solve yourself.”

“If I was assured that it would bring more viewership and more spectators, and it would enhance the sport of tennis, I would be all for on-court coaching,” Evert continued. “But I’m not convinced that it’s going to change the dial. I think people will tune in to the Slams because they’re the Slams.”

If we’re going to try to persuade Brook and officials at the other majors of anything, it should be to hold the line against coaching. Let’s keep Centre Court and Arthur Ashe Stadium what they’ve always been: theaters of battle, where the combatants alone decide their fates. And instead of letting Mouratoglou coach in Ashe, let’s encourage him to let Serena figure things out for herself. She’s done it pretty well in her career so far.

Advertising

The Coaching Question: What is the future of on-court coaching?

ATP/WTA Sydney (1/5 to 1/12)

• Stefanos Tsitsipas, Frances Tiafoe, Simona Halep and Sloane Stephens headline the Sydney International. Watch live coverage on Tennis Channel Plus.

WTA Hobart (1/5 to 1/11)

• Watch the action from the Hobart International featuring Caroline Garcia, Belinda Bencic and Maria Sakkari.

ATP Auckland (1/6 to 1/11)

• See John Isner and Fabio Fognini live on Tennis Channel Plus beginning Monday, Jan. 7 at 6:00 pm ET.

FAST 4—Sydney (1/7)

• The game’s best compete in the always entertaining Fast4 format, with appearances by Nick Kyrgios, Grigor Dimitrov and Milos Raonic. Live coverage begins on Monday, Jan. 7 at 3:30pm ET.

World Tennis Challenge—Adelaide (1/7 to 1/9)

• Watch Borna Coric, CoCo Vandeweghe and Victoria Azarenka live from Adelaide starting Monday, Jan. 7 at 3:00 am ET.

AO Qualifying Rounds (1/8 to 1/11)

• Australian Open officially begins with qualifying action. Tennis Channel Plus has fall the action live! Coverage begins Tuesday, Jan. 8 at 6:00 pm ET.