The First Rafa: Remembering Rafael Osuna

By Steve Tignor May 20, 2019French Open organizers introduce draw to access ticket sales

By Associated Press Jan 07, 2025Coaches Corner: Juan Carlos Ferrero proves essential to Carlos Alcaraz's Roland Garros success

By Steve Tignor Jun 14, 2024What’s next for Novak and Nadal? Four ATP storylines after the Paris fortnight

By Joel Drucker Jun 10, 2024Naomi’s resurgence, Iga on grass: Four WTA storylines after the Paris fortnight

By Joel Drucker Jun 10, 2024Carlos Alcaraz becomes the clay-court champion that he—and we—always knew was possible

By Steve Tignor Jun 09, 2024Coco Gauff wins first Grand Slam doubles title with Katerina Siniakova in dream team debut

By Matt Fitzgerald Jun 09, 2024Coco Gauff is a Grand Slam champion in singles and doubles, exceeding her own expectations

By Associated Press Jun 09, 2024From Rafa to Iga: as one owner of Roland Garros departs, a new one has moved in

By Steve Tignor Jun 08, 2024Roland Garros men's final preview: Carlos Alcaraz vs. Alexander Zverev

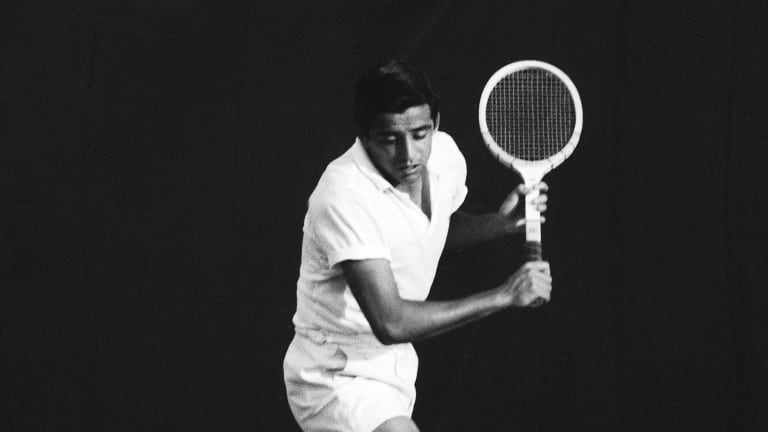

By Steve Tignor Jun 08, 2024The First Rafa: Remembering Rafael Osuna

Rafael Osuna still represents everything we want tennis to be. Fifty years after his tragic death, we remember Mexico’s greatest player, and his place on the greatest college tennis team of all time.

Published May 20, 2019

Advertising

Next week, the most famous names in tennis will gather in Paris, where the 51st edition of the French Open will take place. For 25 lesser-known players, though, the middle of the month was spent 6,000 miles away, on the Pacific coast of Mexico. There they continued another tennis tradition that has lasted almost as long: the Osuna Cup.

The annual event, which was started in 1972 and is named after the most accomplished tennis player in Mexican history, Rafael Osuna, pits former college standouts, national champions and Davis Cup players from the United States and Mexico against each other in a friendly competition. The two countries take turns hosting; the 47th edition will be held this year at the Las Brisas Resort, in Huatulco. At a time when the United States is talking about building a wall between the nations, the Osuna Cup offers a bridge.

Since 2002, Mexico’s captain has been Rafael Belmar Osuna, a nephew of the event’s namesake. He says the Cup has fostered an enduring sense of cross-border camaraderie.

“Besides being a tournament where teams from the USA and Mexico face off athletically,” Osuna says, “it has become a link of friendship between families of both nations.”

The Cup is a fitting legacy for his uncle, who spent his career bridging that same border.

Rafael Osuna was born in Mexico City, but he became a serious tennis player in Los Angeles. He won his first Wimbledon doubles title with an American partner, Dennis Ralston, and his second with a Mexican partner, Antonio Palafox. He led Mexico to its only Davis Cup final, in 1962, but he won his biggest singles title in the States, at the 1963 U.S. Nationals.

The First Rafa: Remembering Rafael Osuna

© AP1964

Advertising

Osuna was a member of one of the greatest college teams of all time, the 1963 USC Trojans. At the same time, he was a link in a chain of Latin players who earned All-American honors at USC, from Alex Olmedo in the 1950s, to Joaquin Loyo-Mayo in the late-’60s, to Raul Ramirez in the ’70s.

“Osuna was one of the great guys; friendly to everyone, he didn’t care who you were,” says Tom Edlefsen, a teammate of his on that 1963 USC team and an Osuna Cup regular. “He never walked by anyone and looked the other way.”

For those reasons, this year’s Osuna Cup came with a bittersweet taste. The event took place three weeks before the 50th anniversary of Osuna’s death, at age 30, in the crash of Mexicana Airline Flight 704 near Monterrey, Mexico, on June 4, 1969.

Just 10 days earlier, Osuna had accomplished one of his longtime goals, when he led Mexico’s Davis Cup team to a win over Australia, in front of a frenzied crowd in Mexico City. With the audience chanting his name, Osuna clinched his county’s first-ever victory over the 17-time champions.

At the time, as fans carried Osuna around the arena, it seemed like an appropriate culmination to a decade in which this most unassuming of superstars had, with his lightning speed and savvy net-play, carved out a place for his country on the world tennis map. But that long-awaited triumph was soon suppressed by tragedy. Osuna was among the last of the 79 passengers to board Flight 704; an hour and a half later, the Boeing 727-64 flew into a storm, and the pilot turned into a 6,000-foot peak. When the plane burst into flames, everyone inside was killed.

Among the dead was the politician Carlos A. Madrazo. A member of the ruling Industrial Revolutionary Party, Madrazo was a reformist who had become critical of the government. Because of his views, there has been speculation that passengers on Flight 704 were victims of foul play. (Osuna’s nephew discounts those rumors.)

Osuna’s remains were found in the mountains near Monterrey. He was identified by the Rolex watch he was wearing, which he had won at Wimbledon in 1960, after making an unlikely run to the doubles title with his fellow USC Trojan, and Wimbledon rookie, Ralston. Over the ensuing nine years, Osuna would find even greater success on court, and leave a legacy that’s ripe for re-appreciation.

Few saw that kind of success coming when Osuna arrived at Southern Cal at the start of the decade.

“He was a tennis hack until he got to USC,” Rafael Belmar Osuna says of his uncle. “He did everything wrong.”

Osuna’s forehand-volley swing was too big, he couldn’t come over his backhand, he didn’t move his feet properly and, like the basketball player he used to be, he used head-fakes when he hit the ball.

But if Osuna was unschooled, USC’s men’s coach, George Toley, knew a quick study when he saw one.

“People asked Toley, ‘Why would you give him a scholarship?’” Belmar Osuna says. “Toley said, ‘Because he moves on the court like a god.’”

Osuna had hands and athleticism to match. At 10, he won Mexico’s national ping-pong championship for adults, despite barely being able to see over the table. At 15, he became the youngest member of the national basketball team. When Osuna brought his talents to the tennis court, Toley discovered something else: his capacity for work.

“Toley had one of the only ball mac-hines around,” Edlefsen says. “It was this big, monster contraption. I spent hours hitting against the thing; the only person who used it more was Osuna.”

If Osuna was in a hurry to learn the game, he had come to the right place, and the right person.

“He was the best coach in the country,” Edlefsen says of Toley, “especially when it came to volley technique. People don’t realize it now, there are half a dozen shots you need to learn at net—every volley is different. Toley had Osuna master all of them.”

The First Rafa: Remembering Rafael Osuna

Advertising

The coach’s touch was so deft that he could conjure a Wimbledon-winning team seemingly from thin air. In 1960, Toley suggested that Ralston, an incoming freshman, team with Osuna for the Wimbledon doubles. They had never played together, and the coach was just hoping that they would “jell” a little before the season. They did, and after eking out their first-round match, 16–14 in the fifth set, they went on to win the title.

When Osuna and Ralston returned to Los Angeles, they came back to a city that was at the center of a college-tennis golden age. From 1946 to 1971, USC and its crosstown rival, UCLA, won 20 NCAA titles—11 for the Trojans, nine for the Bruins. The two schools also served as Davis Cup pipelines: Olmedo, Osuna, Ralston, Stan Smith and Bob Lutz played at USC, while Arthur Ashe, Charlie Pasarell and Jimmy Connors were at UCLA.

Best of all, by long-held consensus, was the 1963 USC team. The Trojans went 12–0, defeated a UCLA team led by Ashe and Pasarell 9–0, won the NCAAs handily, and fielded five players who are now in the ITA Men’s Collegiate Tennis Hall of Fame: Ralston, Osuna, Edlefsen, Ramsey Earnhardt and Bill Bond. That year the NCAA singles and doubles finals were both all-USC affairs: in singles, the team’s No. 1 player, Ralston, beat its No. 2, Osuna; in doubles, they teamed up to squeak past Earnhardt and Bond in five sets.

“We had five of the country’s 10 best players, so that wasn’t bad,” Edlefsen says with a laugh. “We were all good friends, too. We shared a house and pulled all the usual pranks on each other. Rafe was part of all of that with us.”

“The Trojans of 1963 were not only great players,” Toley said, “but great guys and great friends. They had a wonderful camaraderie on that team.”

That camaraderie could transcend borders. While Osuna and Ralston were partners at USC, they were opponents in a 1962 Davis Cup tie in Mexico City. When Mexico completed an upset victory over the U.S., fans swarmed the court; Osuna’s first reaction was to try to make his way through them to console his American friend.

In 1963, Ralston led the U.S. to its first Davis Cup title in five years, while Osuna won the singles title at the U.S. Nationals at Forest Hills. Osuna’s final-round win, in which he baffled 6’3” Frank Froehling by lofting moonballs from well behind the baseline, was a tactical masterpiece. It also launched him to the ITF’s No. 1 world ranking.

As Rafael Belmar Osuna says, summing up that USC squad: “This was a team where the No. 2 player in the lineup was ranked No. 1 in the world.”

With his win at Forest Hills, Osuna moved from the college game to the amateur circuit. He arrived during its sunset years, when the world’s best players—Rod Laver, Ken Rosewall, Lew Hoad, Pancho Gonzalez—had left to join fledgling pro tours. By 1968, the pros had taken over the sport, the Open era had begun, and the amateur game was a thing of the past.

These were the last days of the “tennis bum,” when a merry band of talented eccentrics traveled the world together, playing for love rather than money. Osuna, while taking a job at Phillip Morris, maintained a prominent place in that colorful cast. His speed, grace and good humor provided the sport’s aficionados with some of their most indelible memories.

The First Rafa: Remembering Rafael Osuna

© Getty Images

Advertising

Bud Collins would never forget his trips to see the National Doubles at Longwood Cricket Club, where Osuna and Palafox—“two Mexicans potent as tequila,” in Bud’s words—dazzled the crowd. At Wimbledon in 1963, British reporter Lance Tingay waxed poetic over Osuna’s narrow third-round loss to Manuel Santana: “Artistry came back to Wimbledon and, if justice were done, this would have been the final,” Tingay wrote. “From first to last the contest was sweet symphony.”

Hall of Fame historian Steve Flink still vividly recalls his first encounter with Osuna, in 1965.

“I was 12, and it was my first time at Wimbledon,” Flink says. “I was wandering around and saw Osuna, and his game just got me.

“He was a beautiful player, with a lot of variety. He moved elegantly, and smiled a lot. I was becoming fanatical about tennis, and seeing Osuna inspired my love for it.”

“It was heartbreaking when [Osuna’s] plane went down,” Ralston told author S. Mark Young for his book Trojan Tennis. “We were all stunned and completely distraught.”

When Osuna died, he left behind a wife, Leslie, and young daughter, Claudia. With him went any momentum that Mexican tennis had built in the 1960s.

Yet 50 years later, his memory continues to inspire on both sides of the border. It inspires friendly competition at the Osuna Cup each spring, and inspires fairness and integrity in the college game: in 1969, the ITA created the Rafael Osuna Sportsmanship Award, which is given to the Division I men’s player who best “displays sportsmanship, character, excellent academics, and has had outstanding tennis playing accomplishments.”

In 1979, Osuna was inducted into the International Tennis Hall of Fame. Now Belmar Osuna hopes his uncle will be memorialized in the US Open Court of Champions. Since 2002, the Open has inducted 24 former winners, four of them from countries other than the United States. Each year thousands of spectators pass their plaques as they enter the grounds.

“He won the tournament,” Belmar Osuna says, “but he did more than that. He was a gentleman, he was popular, he brought kids into the game, he represented his country, he played singles and doubles, he graduated from college.”

Rafael Osuna died 50 years ago, but he was all the things we want tennis to be today.

The First Rafa: Remembering Rafael Osuna