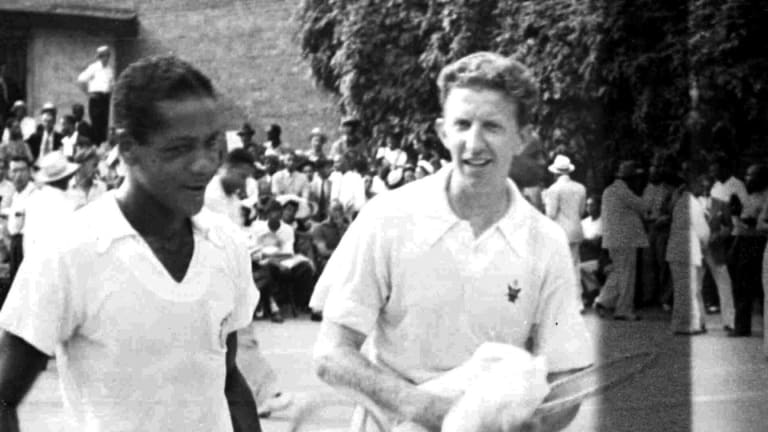

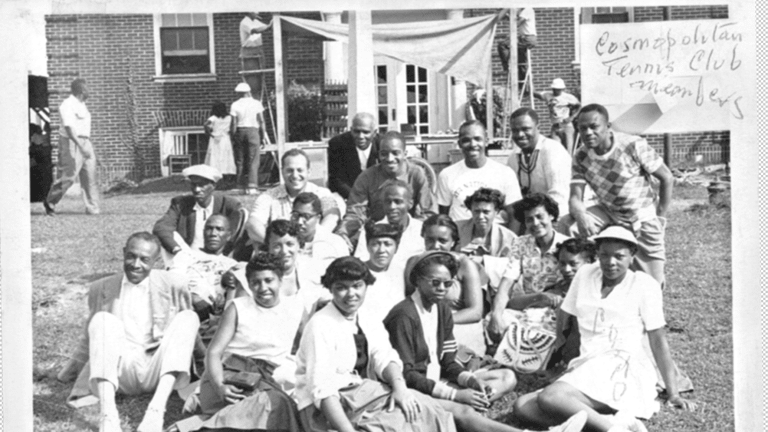

The Pioneer: McDaniel breaks tennis' color barrier—for a day—vs. Budge

By Jul 29, 2020Stat of the Day

Carlos Alcaraz passes Jannik Sinner for No. 1 on year-to-date live race after reaching Monte Carlo final

By Apr 12, 2025Your Game

The Partner ball machine uses robotics to revolutionize tennis training

By Apr 12, 2025Tennis.com Interview

Lorenzo Musetti manifested his 'special' week in Monte Carlo with first Masters 1000 final

By Apr 12, 2025ATP Monte Carlo, Monaco

Carlos Alcaraz charges past Alejandro Davidovich Fokina to reach Monte Carlo final

By Apr 12, 2025ATP Monte Carlo, Monaco

Alex de Minaur: 6-0, 6-0 win over Grigor Dimitrov in Monte Carlo was 'bizarre'

By Apr 11, 2025Social

Stefanos Tsitsipas declines to comment on Goran Ivanisevic coaching rumors

By Apr 11, 2025ATP Monte Carlo, Monaco

Carlos Alcaraz vs. Alejandro Davidovich Fokina: Where to Watch, Monte Carlo Preview, Betting Odds

By Apr 11, 2025Pop Culture

Strive to survive: Film shows the pressure ball kids face to earn an Australian Open spot

By Apr 11, 2025ATP Monte Carlo, Monaco

Alex de Minaur vs. Lorenzo Musetti: Where to Watch, Monte Carlo Preview, Betting Odds

By Apr 11, 2025The Pioneer: McDaniel breaks tennis' color barrier—for a day—vs. Budge

Eighty years ago in Harlem, Jimmie McDaniel and Don Budge played a match at the Cosmopolitan Club. But while McDaniel helped open doors for the sport, he found they were still closed to him.

Published Jul 29, 2020

Advertising

The Pioneer: McDaniel breaks tennis' color barrier—for a day—vs. Budge

Advertising

The Pioneer: McDaniel breaks tennis' color barrier—for a day—vs. Budge

Advertising

The Pioneer: McDaniel breaks tennis' color barrier—for a day—vs. Budge

© AFP via Getty Images

Advertising

The Pioneer: McDaniel breaks tennis' color barrier—for a day—vs. Budge