Acapulco, Mexico

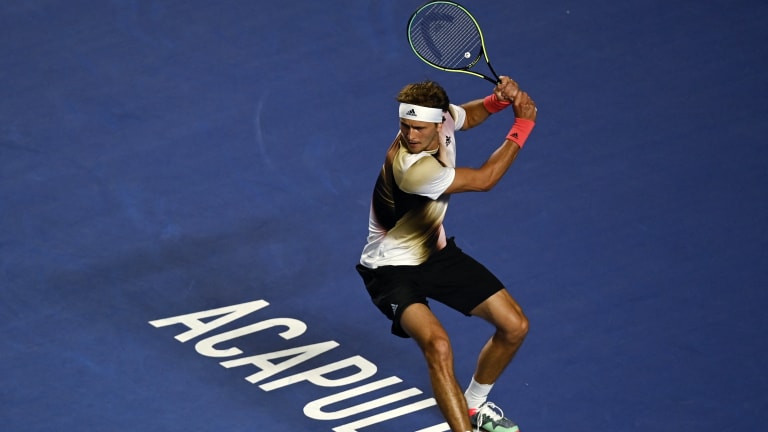

The Wayward Prodigy: It wasn't long ago that Alexander Zverev was being lauded like Carlos Alcaraz is now

By Feb 24, 2022Acapulco, Mexico

Machac-apulco! Tomas Machac captures first ATP title of career in Acapulco

By Mar 02, 2025Acapulco, Mexico

American teenager Learner Tien beats Alexander Zverev, advances to the Acapulco quarterfinals

By Feb 27, 2025Acapulco, Mexico

Stomach issues hit Casper Ruud, Tommy Paul, Holger Rune on day where Acapulco's top five seeds all bow out

By Feb 27, 2025Acapulco, Mexico

American teenager Learner Tien takes out world No. 2 Alexander Zverev in Acapulco stunner

By Feb 27, 2025Acapulco, Mexico

Alex de Minaur defeats Casper Ruud to win Acapulco title for second year in a row

By Mar 03, 2024Acapulco, Mexico

Defending champion Alex de Minaur returns to Acapulco final, where he will meet Casper Ruud

By Mar 02, 2024Acapulco, Mexico

Defending champion Alex de Minaur to face Stefanos Tsitsipas in Acapulco quarterfinals

By Feb 29, 2024Acapulco, Mexico

Daniel Altmaier defeats top seed Alexander Zverev in first round of Acapulco

By Feb 28, 2024Acapulco, Mexico

Ben Shelton narrowly escapes Dan Evans in Acapulco after Tommy Paul falls to Jack Draper

By Feb 27, 2024The Wayward Prodigy: It wasn't long ago that Alexander Zverev was being lauded like Carlos Alcaraz is now

The 18-year-old Spaniard has no pressing need to study the 24-year-old German's misadventures, but cautionary tales are always valuable.

Published Feb 24, 2022

Advertising

Advertising

Zverev and Alcaraz have both taken the ATP by storm at young ages.

© AFP via Getty Images

Advertising

Advertising

After his actions following a doubles match, Zverev was removed from the singles tournament in Acapulco.

© AFP via Getty Images