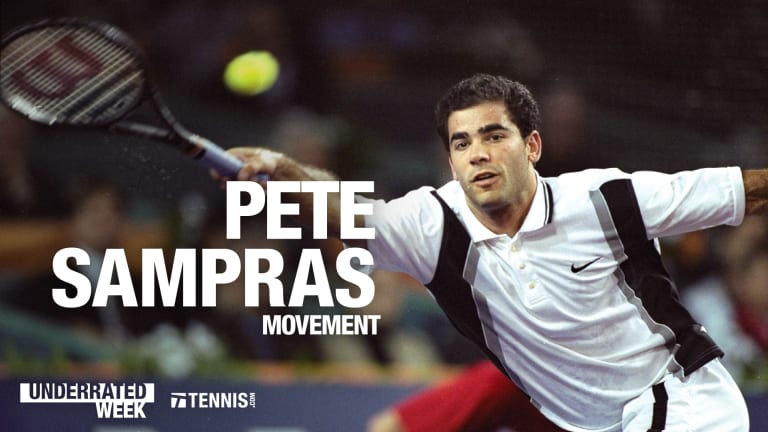

Movement in tennis is often associated with superb dashes across the court. Exemplars include Nadal, Lleyton Hewitt, Bjorn Borg and, one of Sampras’ chief rivals, Michael Chang. These greats were each superb at tracking balls from one corner to another; excellent at that switch-flicking, mid-point transition from defense to offense; and, when necessary, from defense to yet more defense. Consider these great movers maestros of east-west court coverage.

Sampras viewed the map of the court differently. There was a constant angular, diagonal quality to his movement, the sense that victory had much less to do with protecting the horizontal east-west region and pivoted more around seizing the rich north-south territory. To a great degree, this approach had long been present in Southern California, where Sampras grew up and played his tennis on slick hard courts. He’d been a junior member of the Jack Kramer Club, a venue named for the all-time great from the 1940s and ‘50s, Kramer renowned as the pioneer of the serve-and-volley style colloquially known as “The Big Game.”

Sampras’ stylistic role models were the two great Australians, Rosewall and Rod Laver, each fleet-footed masters of all-court tennis. For those Aussies, sharpened largely on grass that was even faster than Southern California hard courts, “all-court” in large part translated into “front court.” To excel at this aggressive playing style, Sampras at the age of 14 had ditched his proficient two-handed backhand and baseline-based game in favor of a one-hander and an increased appetite for charging the net. As he once told me, “I knew with the one-hander I had to move forward. There was no going back.”

It was a textbook example of long-term thinking. At first, Sampras suffered many losses to players he’d previously beaten. By his late teens, though, as Agassi painfully learned that afternoon inside Louis Armstrong Stadium, the investment had paid off.

The composition of today’s tennis courts makes it harder to play like Sampras. Wimbledon in particular has changed, the grass made much slower starting in 2002. But during Sampras’ glory years—seven title runs from 1993 to 2000—the slick velvet lawn was seemingly custom-made for his brand of rapid-fire tennis.

“On grass,” he wrote in his autobiography, “momentum often shifted in the blink of an eye. No points anywhere else were big points in quite the way they were at Wimbledon, because you often got only two or three swings of the racquet with which to win a set.”

You’d be hard-pressed to find any player in tennis history that snapped up those chances as swiftly and proficiently as Pete Sampras.

UNDERRATED TRAITS OF THE GREATS: Roger Federer—Winning ugly | Simona Halep—Boldness | Rafael Nadal—When to come to net | Sofia Kenin—Variety | Pete Sampras—Movement | Serena Williams—Plan B | Novak Djokovic—Forehand versatility | Chris Evert—Athleticism | Daniil Medvedev—Reading the room | Naomi Osaka—Return of serve

RANKINGS: The five most underrated tennis stats | The five most underrated No. 1s | The five most underrated Grand Slam runs

YOUR GAME: Why mental strength is underrated | Five underrated tennis tactics