Tennis is famous for its “If–.” Two lines from Rudyard Kipling’s poem of that name greet every player who walks on to Centre Court at the All England Club. You know the words, the ones about triumph and disaster. A few years ago, Rafael Nadal and Roger Federer were filmed reading that verse and others from the poem—while trying hard, it appeared, not to laugh—for a gauzy Wimbledon promotional video.

Now it seems that Nadal has had enough of “if.” Yesterday, after his 6-2, 6-0, 7-6 (5) loss to Tomas Berdych at the Australian Open, he officially banished the word from the game.

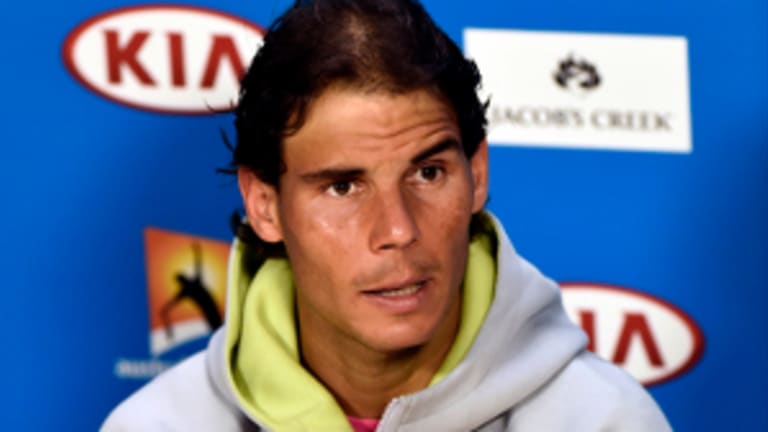

“‘If’ doesn’t exist in sport,” Nadal said when he was asked whether he thought winning the third set would have led to a comeback victory. “That’s the real thing. If, if, if—never comes. The thing is, you have to do it. I didn’t have the chance to play the fourth. I lost the third, so that’s it.”

Nadal is right, of course, and his attitude is the only one a tennis player can have and still maintain his or her sanity. Instead of treating triumph and disaster just the same, you have to forget the disasters entirely.

So forget “if.” Let’s move onto a word that does matter: “Why?” Nadal had won 17 straight matches over Berdych dating back to October 2006. As I wrote after Roger Federer’s defeat at the hands of Andreas Seppi last week, his first in 11 matches against the Italian, if you stick around long enough, the law of tennis averages says that you’re going to lose to a lot of people you normally beat. For Federer, the process began when he was 28; Rafa, who is 28 now, seems to be following in his rival’s footsteps. Last year he lost to Stan Wawrinka, Alexandr Dolgopolov, and Nicolas Almagro, among others, for the first time; yesterday Berdych, his most reliable whipping boy, finally turned the tables.