Roland Garros

Who was Philippe Chatrier, namesake of Roland Garros' roofed court?

By Sep 27, 2020Roland Garros

Rafael Nadal to be honored with 'exceptional' tribute on opening day of Roland Garros

By Apr 17, 2025Roland Garros

French Open organizers introduce draw to access ticket sales

By Jan 07, 2025Roland Garros

Coaches Corner: Juan Carlos Ferrero proves essential to Carlos Alcaraz's Roland Garros success

By Jun 14, 2024Roland Garros

What’s next for Novak and Nadal? Four ATP storylines after the Paris fortnight

By Jun 10, 2024Roland Garros

Naomi’s resurgence, Iga on grass: Four WTA storylines after the Paris fortnight

By Jun 10, 2024Roland Garros

Carlos Alcaraz becomes the clay-court champion that he—and we—always knew was possible

By Jun 09, 2024Roland Garros

Coco Gauff wins first Grand Slam doubles title with Katerina Siniakova in dream team debut

By Jun 09, 2024Roland Garros

Coco Gauff is a Grand Slam champion in singles and doubles, exceeding her own expectations

By Jun 09, 2024Roland Garros

From Rafa to Iga: as one owner of Roland Garros departs, a new one has moved in

By Jun 08, 2024Roland Garros

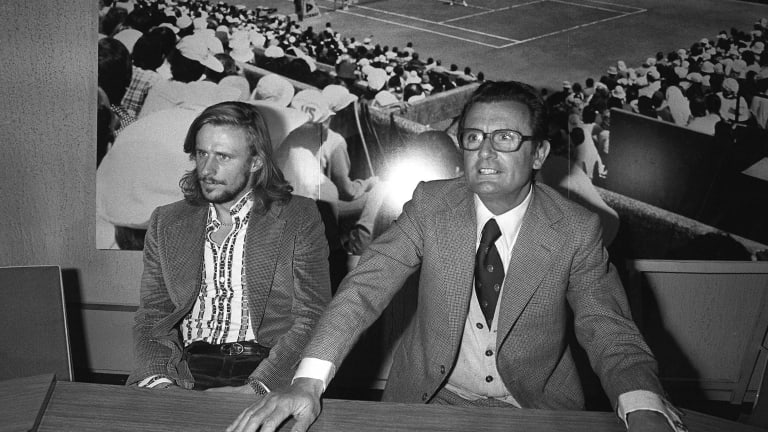

Who was Philippe Chatrier, namesake of Roland Garros' roofed court?

He was a man who changed the face of French tennis and, as president of the International Tennis Federation between 1977 and 1991, influenced much of the tennis world.

Published Sep 27, 2020

Advertising

Who was Philippe Chatrier, namesake of Roland Garros' roofed court?

© AFP via Getty Images

Advertising

Who was Philippe Chatrier, namesake of Roland Garros' roofed court?

© AFP via Getty Images

Advertising

Who was Philippe Chatrier, namesake of Roland Garros' roofed court?

© Getty Images

Advertising

Who was Philippe Chatrier, namesake of Roland Garros' roofed court?