Swiss Watch: What will a busy, and likely pivotal, 2020 bring Federer?

By Joel Drucker Jan 07, 2020Australia at Last: Reflections on a first trip to the AO

By Jon Levey Jan 29, 2025Alexander Zverev must elevate his game when it most counts—and keep it there

By Peter Bodo Jan 27, 2025Jannik Sinner draws Novak Djokovic comparisons from Alexander Zverev after Australian Open final

By Steve Tignor Jan 26, 2025Alexander Zverev left to say "I'm just not good enough" as Jannik Sinner retains Australian Open title

By Matt Fitzgerald Jan 26, 2025Jannik Sinner is now 3-0 in Grand Slam finals after winning second Australian Open title

By TENNIS.com Jan 26, 2025Taylor Townsend and Katerina Siniakova win second women's doubles major together at the Australian Open

By Associated Press Jan 26, 2025Madison Keys wins her first Grand Slam title at Australian Open by caring a little bit less

By Steve Tignor Jan 25, 2025Henry Patten, Harri Heliovaara shrug off contentious first set to win Australian Open doubles title

By Associated Press Jan 25, 2025Aryna Sabalenka takes a rare loss in Australian Open slugfest

By Pete Bodo Jan 25, 2025Swiss Watch: What will a busy, and likely pivotal, 2020 bring Federer?

The 20-time major champion's game has changed with the times, but time hasn’t changed his competitive zeal.

Published Jan 07, 2020

Advertising

Each year, shortly after Roger Federer’s arrival at the National Tennis Centre in Melbourne, a locker room attendant hands him a letter-sized envelope. Inside the envelope is a handwritten note wishing Federer good luck at the Australian Open.

The author of the letter is the legendary Ken Rosewall, who ranks alongside Rod Laver as two of the greatest Australians in tennis history. Federer’s affinity with Laver is apparent, from emotional awards ceremonies to a flair for brilliant shots to the Swiss’ creation of the Laver Cup. Lesser known is the common ground Federer occupies with Rosewall: ballet-like footwork, sublime precision and, as reward for such dedicated craftsmanship, extraordinary longevity. Federer won the Australian Open at the ages of 35 and 36; Rosewall’s last of four titles at this event came at 36 and 37.

As the 38-year-old Federer begins 2020, he faces this obvious question: Can he win another major? Better yet, what needs to happen for Federer to earn Grand Slam No. 21?

An even sharper question: What essential elements does Federer possess that allow him, at this age, to be considered a significant factor?

“Roger’s like Tom Brady,” said longstanding coach Nick Bollettieri. “They both see the whole field brilliantly, and they both take care of themselves superbly.”

Asked if he wished to connect with Federer beyond the formal distance of a letter, Rosewall demurred. The last thing he’d want to do, said Rosewall, was to impose himself on Federer.

Swiss Watch: What will a busy, and likely pivotal, 2020 bring Federer?

Advertising

Federer’s last major title came in Melbourne two years ago, when he held off Marin Cilic in five sets. Should the Swiss claim his 21st Grand Slam crown, the 38-year-old would become the oldest major champion in the Open era, surpassing Rosewall. (Getty Images)

Impose? Isn’t that what dominant champions have always done? They dictate, their conduct a relentless, ruthless proclamation, from playing style to obsessive-compulsive rituals to long-cherished racquets that they usually resolve to wield ‘til death do them part. At the top, loneliness is the cost, but, so it goes, stubbornness is the virtue. Ponder the steel-eyed resolve of Novak Djokovic, Rafael Nadal, Pete Sampras, Ivan Lendl, John McEnroe, Bjorn Borg, Jimmy Connors, Billie Jean King, Chris Evert, Martina Navratilova, Stefanie Graf, Monica Seles, Serena Williams: kill or be killed.

Federer, on the other hand, has transformed the champion’s traditional combat zone.

“He’s got to be the most chilled out No. 1 ever,” says Paul Annacone, who coached Federer from 2010 to 2013, and also worked for years with Sampras.

“You’d have to go back to the great Aussies—Roy Emerson, Laver, Rosewall—to find a top player as classy and gracious as Roger,” says Allen Fox, a former Wimbledon quarterfinalist and expert on tennis’ mental game. “He takes care of people and is always so incredibly kind.”

Here again, the Aussie connection: Federer attuned to the land Down Under and its unsurpassed ability to combine competition and camaraderie. This makes sense. In his formative years, Federer’s primary coach was an Australian, the late Peter Carter. And for what it’s worth, in Federer’s early teens, his father, Robert, considered relocating to Australia.

“He’s the greatest sportsman of all time, maybe in any sport,” says Tennis Channel analyst Jimmy Arias. “He deals with the people, the press, all of the pressures that go with being at the top, so well.”

Witness Federer around a tournament—practices, interactions with fans, sponsors, officials, journalists and, yes, opponents—and there’s a sense of a man never moving upstream, never rushed, naturally aware that there is time for everything and everyone. Here we reach the essence of Federer, of a man who is self-contained, but not purely self-absorbed. As a trademark Federer saying goes, “It’s nice to be important, but it’s more important to be nice.”

Might empathy—or, at least, awareness of others—be Federer’s point of difference inside the lines? Start with a phrase often stated by tennis players of all skill levels: I need to play my game. My game. Me.

Swiss Watch: What will a busy, and likely pivotal, 2020 bring Federer?

© 2019 Getty Images

Advertising

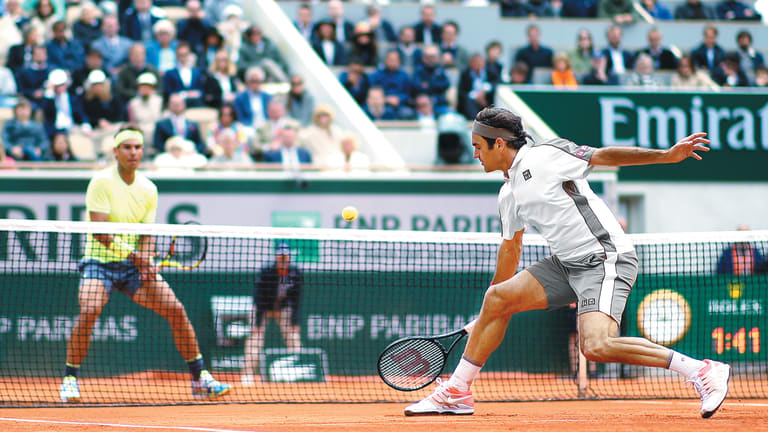

In 2019, Federer returned to Roland Garros for the first time in four years. While it ended with a decisive semifinal defeat to chief rival Nadal in the semifinals, Federer turned the tables on the Spaniard at Wimbledon, winning their semifinal clash in four sets. (Getty Images)

But in Federer’s case, his game is an expression of other games.

“Federer has this way about him that allows us to see the past,” says Robert Lake, an instructor in the Sport Science department of Douglas College who edited the book, Routledge Handbook of Tennis: History, Culture and Politics. “He’s playing the game the way it was meant to be.”

If the strokes are Federer’s hardware, consider his deployment the software: the apps that bring it all to life in unusual ways.

“You and your opponent are one,” said the martial artist Bruce Lee. “There is a coexisting relationship between you. You coexist with your opponent and become his complement, absorbing his attack and using his force to overcome him.”

Federer conducts a patient probe and measured dissection. This was similar to how Rosewall operated.

“Even if you won the first set versus Kenny,” says former pro Marty Riessen (who was 6-15 against Rosewall), “you felt like you’d just been in a dentist’s chair, and the drilling was just about to get more painful.”

Leave the prosecutor-like imposition to others. Like Rosewall, Federer relates. Not my game. Our game. Us.

Of course, it’s usually the case that Federer is the one twisting the hands of the clock. Has any tennis player ever been so adept at creating plenty of time for himself, while concurrently taking away time from his opponents?

Federer accomplishes that less with a sledgehammer and more with a scalpel. The Chinese philosopher Lao Tzu crafted words that describe Federer’s approach to life and tennis: “Softness triumphs over hardness, feebleness over strength. What is more malleable is always superior over that which is immoveable. This is the principle of controlling things by going along with them, of mastery through adaptation.”

When he was 14, Federer left home to train each week at a tennis academy in the French-speaking part of Switzerland. At the time, he only spoke Swiss-German and English. Here, at this early age, adaptation became a vital element of the Federer makeup.

“He can adjust so well,” says Lendl. “He is so adaptable. No one pattern is going to work against him. You have to do multiple things. You have to keep changing.”

Swiss Watch: What will a busy, and likely pivotal, 2020 bring Federer?

© AFP via Getty Images

Advertising

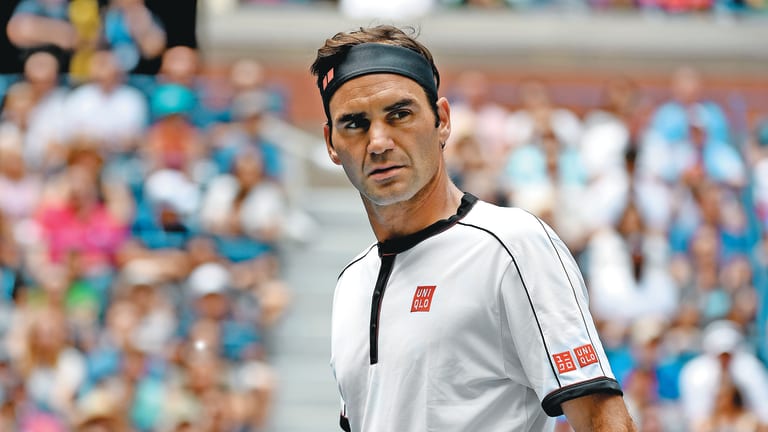

Even at 38, Federer appears committed to an arduous 2020. Worry all you want about what’s ahead for him. He’s likely not. (Getty Images)

And so he has. Most champions have one playing style that they might alter slightly, with a technical or tactical enhancement. Over the course of his career, Federer has had three.

Early on, there was the bold, net-rushing, shot-maker. Then, the man who started winning majors in 2003 had transformed into a swift, solid, versatile baseliner, who relied heavily on movement and frequently sliced his backhand.

Then came something extraordinary. Having suffered a knee injury that took him off the tour for the second half of 2016, a 35-year-old Federer came to Melbourne ranked No. 17 and likely more uncertain than ever of what twists his tennis would take.

“I was really, really happy just to win, to be out there,” he said after his first-round win in 2017 over longstanding peer Jurgen Melzer.

Easy as it would have been for Federer to return and play quite similarly, this was not the case. After a few experiments, he’d at last figured out how to harness the power of a racquet with a bigger head size. He’d also opted to change his court position, stationing himself on the baseline.

“He had to learn how to take time away, especially with his one-handed backhand,” says former Top 10 player Tim Mayotte.

Voila—Federer unleashed a new and more powerful topspin backhand, after all those years and titles.

“I don’t think anyone has ever played more aggressively,” says Hall of Famer Mats Wilander.

“He’s just standing on the baseline, ripping shots. He’s able to control 80 percent of the points.”

Slamless since 2012, Federer gobbled up three more in 2017 and ’18—two Aussie Opens and, without the loss of a set, a men’s record eighth Wimbledon.

“His vast tennis vocabulary was back,” says Mary Carillo. "The languid style, the cool intelligence.”

Federer’s record 20 majors are the biggest jewels in his crown. But then there’s this gob-smacking number: 22. According to Ubitennis.net, that’s the number of times Federer has lost after holding match point—including six times at the majors. None, of course, was more prominent than last summer’s Wimbledon final, against Djokovic, when Federer served in the fifth set at 8–7, 40–15—and then proceeded to play two of the sloppiest points of his career, the first marred by poor footwork and a wide forehand, the second a forced approach shot. The opportunity gone, Federer subsequently played a miserable tie-breaker.

Swiss Watch: What will a busy, and likely pivotal, 2020 bring Federer?

© AFP via Getty Images

Advertising

Six months after failing to close out Djokovic in the Wimbledon final, Federer’s decision making under pressure will be heavily examined in 2020. (Getty Images)

Likely no Wimbledon match more personified Rudyard Kipling’s words above the entrance to Centre Court: “If you can meet with triumph and disaster and treat those two imposters just the same.”

Wilander’s belief is that, because Federer was hardly tested in his prime years of dominance, he never learned to win big points. The likes of Andy Roddick, Lleyton Hewitt, Marat Safin and David Nalbandian may have had fine moments of grit and skill, but they were nowhere near as skilled or versatile as Federer.

“Only Nadal was pushing him when he was at his peak,” says Wilander.

Arias concurs: “Early in his career, he would win so easily. So then when he was in a tight spot, he wouldn’t always come through.”

“I’m sure he was really rocked by Wimbledon,” says Annacone. “But then he has also told me about Slams he won where maybe he should have lost.”

As basketball legend Michael Jordan once said, “Twenty-six times, I’ve been trusted to take the game-winning shot and missed. I’ve failed over and over and over again in my life. And that is why I succeed.”

“If you’re that close, you’re encouraged,” says Tennis Channel analyst Martina Navratilova, who like Federer, lost a Wimbledon singles final when she was 37. “Because Roger’s playing so well, maybe he doesn’t feel much pressure that time is running out.”

Even at 38, Federer appears committed to an arduous 2020, including plans to play Roland Garros (which he skipped from 2016-’18) and the Olympics, where Federer’s best singles showing was a silver medal in 2012.

Federer also surely feels the pressure of peers seeking to surpass his record tally of major singles titles. Nadal, 33, holds 19. Djokovic, one year younger, has 16. It’s a near certainty that each will have more chances than Federer to win Slams in the years to come.

Swiss Watch: What will a busy, and likely pivotal, 2020 bring Federer?

© 2019 Getty Images

Advertising

Federer is in position to reach 100 match wins in Melbourne, holding a 97-14 record at the Happy Slam thanks to reaching the semifinal stage or better in 14 of his past 16 appearances. (Getty Images)

Though a player’s total number of majors is but one metric of tennis supremacy, this month’s Australian Open represents an excellent opportunity for Federer to distance himself from his two biggest rivals.

“He has a better chance at Australia even than Wimbledon,” said Wilander. “There’s no chance of him being dented from the previous seasons.”

Lendl agrees: “Roger always seems so fresh in Australia, and others aren’t quite as sharp yet.”

And while there probably won’t be a Federer 4.0 in Melbourne, perhaps the 3.1 version will surface.

“I’d like to see him serve and volley a bit more, maybe once or twice a game,” says Navratilova. “And why not bring back the SABR?”

The Australian Open is yet another chance for Federer to control time, both inside the lines and versus the ticking hands of history. That is, if he can navigate such factors as Melbourne’s occasional triple-digit temperatures and a slew of familiar and younger foes, such as Stefanos Tsitsipas, who ended Federer’s Oz run last year.

Or the physical demands needed to prevail at Roland Garros. Or the non-stop summer jet set that will send Federer to London, Tokyo and New York.

Worry all you want about what’s ahead for Federer. He’s likely not.

“I’ll tell you what I can’t wait for with Roger,” says Wilander. “I want to be sitting in my rocking chair, listening to him explain tennis to me. He knows things about the game none of us know. He’s the Einstein.”

Like Federer, Albert Einstein keenly understood the nuances of time. “I don’t think about the future,” said the theoretical physicist. “It comes soon enough.”

No doubt Federer would nod approvingly upon learning that Einstein conducted a great deal of his finest work in Switzerland.