The toss connection—hit or pitch: How baseball is similar to tennis

By Mar 26, 2020Lifestyle

Roger Federer’s Wimbledon-winning racquet sells for more than $100,000 in tennis auction

By Feb 10, 2025Pop Culture

Roger Federer explains tennis scoring, On logo to Elmo in Super Bowl ad

By Feb 10, 2025Lifestyle

Roger Federer’s Wimbledon winning racquet currently up for auction

By Jan 28, 2025Australian Open

Henry Bernet, Australian Open junior champion, takes inspiration from fellow countrymen Roger Federer and Stan Wawrinka

By Jan 25, 2025Style Points

The best tennis fashion moments of 2024: Federer & Nadal for Louis Vuitton, Kostyuk's viral Wimbledon dress and more

By Dec 14, 2024Style Points

The year of Tenniscore: How the 'Challengers' effect transformed tennis fashion in 2024

By Dec 09, 2024Facts & Stats

Most wins in 2024: Jannik Sinner joins exclusive list with sparkling 73-6 record this year

By Dec 04, 2024Nadal's farewell

'Your old friend is always cheering for you': Roger Federer pens letter to retiring Rafael Nadal

By Nov 19, 2024Nadal's farewell

22 Rafael Nadal quotes that sum up his fighting spirit and unique sense of humor

By Nov 18, 2024The toss connection—hit or pitch: How baseball is similar to tennis

If not for the coronavirus pandemic, today would have been Major League Baseball's Opening Day. Earlier this week, both sports' Olympic events were postponed until 2021.

Published Mar 26, 2020

Advertising

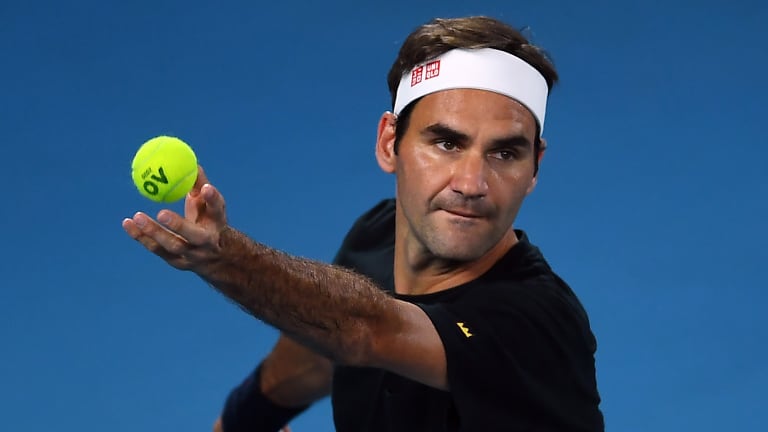

The toss connection—hit or pitch: How baseball is similar to tennis

© Getty Images

Advertising

The toss connection—hit or pitch: How baseball is similar to tennis

© Getty Images

Advertising

The toss connection—hit or pitch: How baseball is similar to tennis

© AFP via Getty Images

Advertising

The toss connection—hit or pitch: How baseball is similar to tennis