The Rally: How tennis brings sense of community to college experience

Apr 06, 2020With clay titles, Jenson Brooksby and Jessica Pegula made 2025 all the more promising

By Steve Tignor Apr 07, 2025Returning Jenson Brooksby beats Frances Tiafoe in Houston to win first ATP title

By Associated Press Apr 06, 2025Game, Set, Bet, presented by BetMGM: Will Carlos Alcaraz win Monte Carlo?

By Zachary Cohen Apr 06, 2025Jessica Pegula fights through fatigue to win Charleston title against Sofia Kenin

By TENNIS.com Apr 06, 2025Charleston Open will pay women same as men starting in 2026

By Associated Press Apr 06, 2025Racquet Review: Wilson Clash 100 Pro v3

By Jon Levey Apr 06, 2025Richard Gasquet, 38 and a wild card, wins opener in final Monte Carlo Masters

By Associated Press Apr 06, 2025Carlos Alcaraz and Novak Djokovic practice together at Monte Carlo Masters

By Baseline Staff Apr 06, 2025Charleston Betting Preview: Sofia Kenin vs. Jessica Pegula

By Zachary Cohen Apr 06, 2025The Rally: How tennis brings sense of community to college experience

Can we replicate the college-team attitude in other areas of recreational tennis?

Published Apr 06, 2020

Advertising

Over the next three days, we'll look at how the coronavirus crisis has impacted one aspect of tennis in a particularly cruel way: the college game.

On Monday, Steve Tignor looks back on a season at the top for the University of Southern California men's team—before it suddenly stopped. He also speaks with Joel Drucker, in the #MondayRally, about the communal side of college tennis, and if it can be replicated elsewhere in the sport.

On Tuesday, Ed McGrogan writes about Fairfield University's women's team, which made an unlikely run to the NCAA Tournament in 2019. But in covering the mid-major school this March, he got an up-close look at the abrupt sadness that followed.

On Wednesday, Nina Pantic examines the NCAA's ruling that grants spring-sports athletes another year of college eligibility, if they so choose.

Steve,

It’s been heartwarming to be in touch with so many tennis lovers and hear tales of what makes the sport so meaningful to them and how much they are missing it now. What’s coming through quite clearly is that, while it’s tempting to think of tennis as an individual sport, that doesn’t fully paint the whole picture.

Running strikes me as far more of a purely individual sport. And as I ponder going on runs these days, since I can’t play tennis, I’m now even more painfully aware of how different it is than the court sport. Running is, quite frankly, boring. Tennis is a relationship sport, of two or four people going back-and-forth, connected to one another, be it cooperating via hitting or mutually engaged destruction through competition.

“Friendly doubles?” a good buddy of mine once asked. “Friendly doubles is when you and I try to kick each other’s butts and then have drinks after.”

Whether you’re hitting or competing, there’s a communal aspect to tennis—a social dimension to being across the net from someone that’s deeply missed right now.

And perhaps no form of tennis-as-community has been more affected by current events than college tennis. Earlier this week, I spoke with Brandon Holt, who plays number one on the top-ranked University of Southern California (USC) team. When I asked him what makes college tennis different from other forms of the game, he said, “Just about everything. Junior tennis is way more similar to professional tennis. You’re just by yourself.” But in college tennis, he said, “You can lose your match versus another team and it doesn’t matter. I’m not thinking about the match I lost. I’m thinking about how we won.”

Advertising

A senior this year, Brandon was excited about the possibility of his team winning the NCAA championship. Just over three weeks ago, USC was scheduled to head west across town to play its biggest rival, UCLA. The day prior, per a frequent ritual, he and his doubles partner and one-time roommate, Riley Smith, hit on the UCLA courts. It had already been determined that no fans would be allowed to watch, itself a rather strange arrangement. The next morning, Brandon and his teammates were loading the team van to head to UCLA.

Rapidly, that morning, word came that the match was cancelled—and soon enough, the entire season.

“It all went so fast,” Brandon said. “It was all so sudden. Of course, there are more important things going on now than tennis, so it’s good to keep everything in perspective.”

As we spoke more, he said that it wasn’t the matches he missed. It was his mates, the practices most of all.

You’re playing with guys who are with each other 24/7,” he said. “You’re with your tribe, battling toe to toe against one another.”

When they weren’t on the courts, they were in the nearby gym, or having meals together.

“No one wanted to spend time with anyone else,” he said. “We’d study, or at least try to study. . . We really had a community of love.”

Soon after the UCLA match was cancelled, Brandon returned to his family’s home in the Los Angeles area to hunker down with his parents—Scott Holt and Tennis Channel colleague Tracy Austin—as well as his two brothers, Dylan and Sean. Brandon and his teammates continue to stay in touch through daily chats. He’s also still taking his classes online, likely to earn a degree in real estate later this spring. Having cracked the Top 500 on the ATP rankings list, he was planning this summer to play Challenger events. But now he also knows that the NCAA will give seniors a chance to play tennis in 2021.

I intend to stay in touch with Brandon. Looking further down the road, it will be fascinating to see how he continues to develop—not just as a tennis player, but as a young man, shaped deeply by a massively tragic and challenging global crisis.

Steve, unlike me, you played college tennis. So certainly you’ll have a distinct perspective here too.

Joel,

We seem to be on the same beat. Last week I talked to USC’s men’s coach, Brett Masi, about what it was like for the team to have a national title in its sights, and then see the season suddenly…stop. Masi will probably be happy with the NCAA’s ruling that allowed spring-season seniors to return in 2021. He told me he’d “love to do it all over again, see if we can win it.”

This was Masi’s rookie season. He was taking over for Peter Smith, who had won five NCAA championships—with a little help from Steve Johnson—in his 17 seasons at USC. Like Holt, Masi talked about how close the team was, which he called “awesome and refreshing.”

This isn’t always the case on teams, of course, but then again, not every team gets to have a legitimate shot at a national title. For USC this year, every match and every practice must have felt as if it were part of something bigger, an opportunity to pull together in pursuit of an historic achievement.

The Rally: How tennis brings sense of community to college experience

Advertising

Swarthmore College

I experienced that, on a smaller scale, when I played tennis at Swarthmore from 1988 to ’91. One of the reasons I chose the school was that the team was always in the mix for the Division III national championship. Under its coach at the time, Mike Mullan (Berkeley ’71), they had won the title twice in the previous decade, and from the start our group was always ranked in the Top 5. My sophomore year we lost the championship match, and spent the next 24 hours staring at a hotel TV in shattered silence. The following year, when we won the championship, we bolted onto the court like a pack of berserk Jim Valvanos, looking for someone to hug. That’s one of the beauties of college sports to me; it gives thousands of kids a chance to experience a range of emotions that are every bit as intense as the ones that, say, the world’s top players experience when they compete at Wimbledon.

You’re right to say that tennis isn’t necessarily an individual sport, Joel. It’s college itself that’s relentlessly individualistic. It’s broadening, but also isolating and just as cliquey as high school. No matter how much you learn and how many friends you make, you take your exams and earn your grades on your own. For me, tennis was a refuge, from cramming and procrastinating. The courts become one of the places on campus where you don’t feel alone, and where you have a goal you can share.

My question to you is: Can we replicate the college-team attitude in other areas of recreational tennis?

Steve,

That’s such a great story about your college tennis experience. Fantastic to learn how being on a team helped you counterbalance the solitude of school. This sure seemed the case when talking to Brandon. I was struck by how he revealed that it wasn’t so much the competition and the matches he missed. It’s the camaraderie—the chance to engage in tennis with people he cares about deeply.

As far as that college-team attitude in recreational tennis goes, the obvious means for that in our country is league tennis. Certainly there are tales of hearty teams, joyful celebrations and fun road trips. But I’ve also been on league teams where a guy playing singles will play his match and leave. Or other teams where no one cares to practice even the day of the match. Or teammates who show up with injuries rather than tell the captain they’re too hurt to play and give someone else the chance to play. Or doubles duos who after their match is over, keep playing for fun with their opponents rather than pay attention to the active matches.

There’s also a deeply political aspect regarding who gets to play, doubles pairings and more. In other words, while recreational players gladly transact tennis business with one another, it’s not always clear if they necessarily care about one another. To be sure, I wonder about that myself when it comes to the people I play with. Writing this makes me think I should check in with five of them right now.

So perhaps what’s at play here is the eternal American conflict between self and society. A great many of us who come to tennis were drawn to the sport because of its credo of individualism. I once asked John Lucas, an All-American in tennis and basketball—and an NBA player—which sport is harder.

“Tennis. You have to take the shot every time,” he said. “You can’t pass and you have to play every minute of the entire game. But basketball might make you a better person because you learn to work with people.”

The Rally: How tennis brings sense of community to college experience

© Getty Images

Advertising

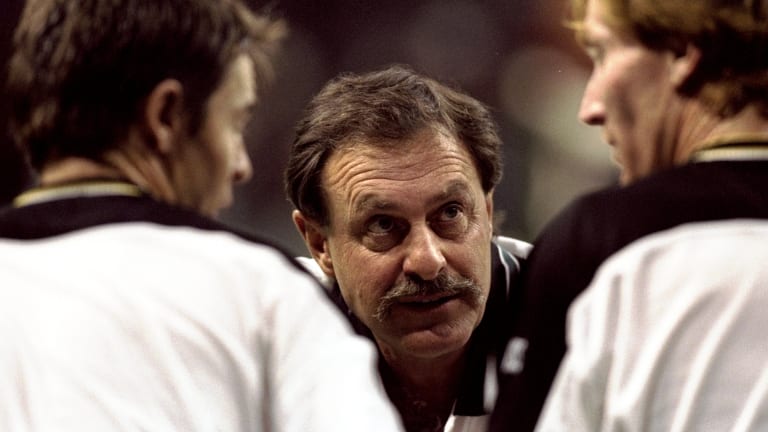

John Newcombe, Australian Davis Cup captain, with Todd Woodbridge and Mark Woodforde, in 1999. (Getty Images)

On the other hand, to Australians, there’s no significant disparity between the individual and the group. For 25 years, I’ve gone to John Newcombe’s fantasy camp, where recreational players are drafted on to teams. The first day I went there, Newcombe said, “You guys all think you’re pretty good back at your clubs. Well let’s see what happens when your mates are counting on you—and when you’re through playing, do you stick around and cheer them on?” Believe me, when a guy who’s won 26 Slams tells you what it means to be part of an ensemble, you hum accordingly. One year at that camp, I’d blown a big lead and lost. But I knew that I only had about one minute to let it go and head two courts over to support my buddy Mark.

It’s always going to be hard to truly make recreational tennis as much of a team sport as softball or basketball. But perhaps there are ways both players and tennis community leaders can take subtle steps. Maybe doubles foursomes should constantly broaden the mix of participants so that there’s an ongoing and evolving flock of six to ten people who can comprise a weekly doubles outing—with time after always allocated for drinks and snacks. Or those who run facilities should constantly be organizing small, informal mixer events that make it easy for both longstanding and new members to get to know one another and start scheduling matches.

And when I think of what’s happening in the world now, you’ve got to think that out the other end, there will be tremendous gratitude merely for the chance to hit with anyone. While I totally understand why most of us play mostly want to play with people approximately within our skill range, sometimes this gets a little too snobby. Years ago, on a vacation at a hotel in Hawaii, I asked the tennis director if there were any guests looking to hit. He called me back and said, “Yes, but this gentleman says he doesn’t want to play with anyone who’s less than a 5.0 player.” Can you imagine someone having enough gall to say that in the future? And again, pondering all this makes me realized that I should check in more these days with my tennis mates.

In addition to your great college time, Steve, what have been your experiences of tennis as community?

Joel,

When I think of favorite personal tennis moments, the images that come to my mind don’t have anything to do with hitting forehands or backhands, or even winning matches. They have to do with people. Here’s an example that has stayed in my mind, and changed in my mind, over the years.

It’s the summer of 1983, and I’m sitting in the dreaded middle seat in the back of my friend’s parents’ brown Ford sedan as we make the two-hour—i.e., endless—drive from Williamsport, PA, our hometown, to Altoona for a junior tournament. I’m the youngest person in the car, so I have the honor of sitting with my knees in my face, and getting squeezed by bigger kids from both sides. At the start of the week, there are four other players riding with me. Three boys and two girls—plus my friend’s mom, the driver—fill the beige vinyl seats.

On the way to the tournament in the morning, we’re quiet. We have our short shorts on, and our tube socks pulled up, and our Kramers and Bancrofts and Donnays are in the trunk. We’re ready, sorta. Inside our heads, though, I think all of us are repeating the prayer that every junior tennis player repeats on the way to a tournament: “Please God, let my opponent be awful, be so bad there’s no possible chance I could lose to him even on my worst day.” In my mind, the only sound is the Eurthymics “Sweet Dreams,” playing over and over on the little radio at the front of the car, the way it did that entire year.

Advertising

Each day we drive to a public park in Altoona, and play our matches—a lot of them, two singles and two doubles, from 9:00 in the morning to 5:00 in the afternoon. We watch each other’s singles matches, and play doubles together. We go to McDonald’s. We lay back on the metal bleachers and gossip. I’ve just finished eighth grade, and it’s a thrill to be able to talk freely with ninth and 10th graders. If it weren’t for tennis, they wouldn’t give me the time of day. On the way back, we’re rowdy. Some of us have won, some have lost, but the point is: Our matches are over, and that’s a relief. The boys play air guitar to the Def Leppard song on the radio; the girls scream along with “Total Eclipse of the Heart.”

One by one, as the week goes on and some of us start to lose, the other kids vanish and seats open up in the car. By Saturday, I’m the only one left in the draw, and I make the trip to play the final by myself, in the passenger seat next to my mom, with the radio off.

That year I win the final, after losing it the previous year. It’s a satisfying feeling to put the (small) trophy next to me in the car on the way home. At the time, I thought that moment was what the whole week was about, and that winning that trophy was the sole reason I’d gone to Altoona all week.

So why, all these years later, had I forgotten all about that trophy, and about winning that tournament? Why instead, did I remember every detail of my time in the car with my friends? Why, when I think about the summer of ’83, is listening to “Sweet Dreams” over and over, jammed into a tiny car with five other laughing, shrieking teenagers in the heat of summer vacation, the memory I cherish most?

The Rally: How tennis brings sense of community to college experience