A Tale of Two Soldiers, and Tennis Players: Jack Kramer and Joe Hunt

By Steve Tignor Sep 07, 2020US Open revamps mixed doubles format, adds $1 million prize to incentivize "biggest names in the sport"

By Associated Press Feb 11, 2025US Open adds a 15th day, moves to Sunday start in 2025

By Associated Press Jan 29, 2025Post-2024 US Open WTA storylines: The Age of Aryna; what's next for Swiatek and Gauff?

By Joel Drucker Sep 09, 2024Post-2024 US Open ATP storylines: The race between Alcaraz and Sinner for No. 1 ... and more

By Joel Drucker Sep 09, 2024Jannik Sinner’s US Open title run won’t clear the air around him entirely

By Steve Tignor Sep 09, 2024Taylor Fritz fails in US Open final, but hope springs for American men's tennis

By Peter Bodo Sep 09, 2024Jannik Sinner storms to second major title, defeats Swift, Kelce-backed Taylor Fritz at US Open

By David Kane Sep 08, 2024Jessica Pegula's willingness to take chances paid off at the US Open

By Peter Bodo Sep 08, 2024Aryna Sabalenka won her first US Open by learning from her past heartbreaks in New York

By Steve Tignor Sep 08, 2024A Tale of Two Soldiers, and Tennis Players: Jack Kramer and Joe Hunt

World War II ended 75 years ago last week. Today, we look back at the 1943 Forest Hills final between two U.S. servicemen, and how their fates were determined—fortunately in one case, tragically in the other—by their experiences in the conflict.

Published Sep 07, 2020

Advertising

“Strapping blond Californians of serve-and-volley persuasion.” That’s how one tennis historian described the two players who faced off in the final of the U.S. Nationals at Forest Hills in 1943.

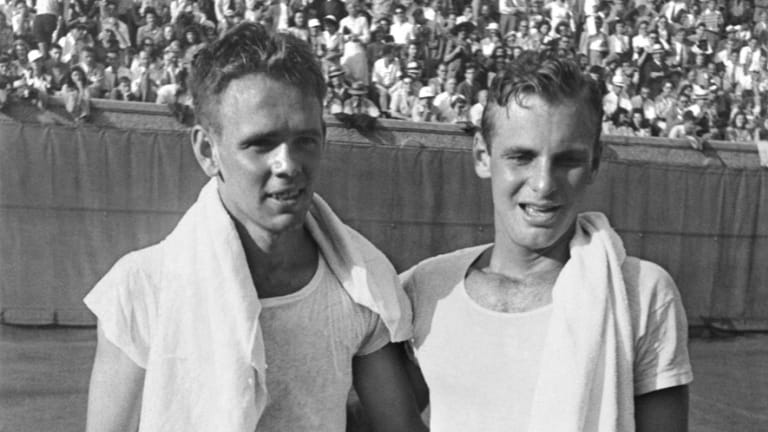

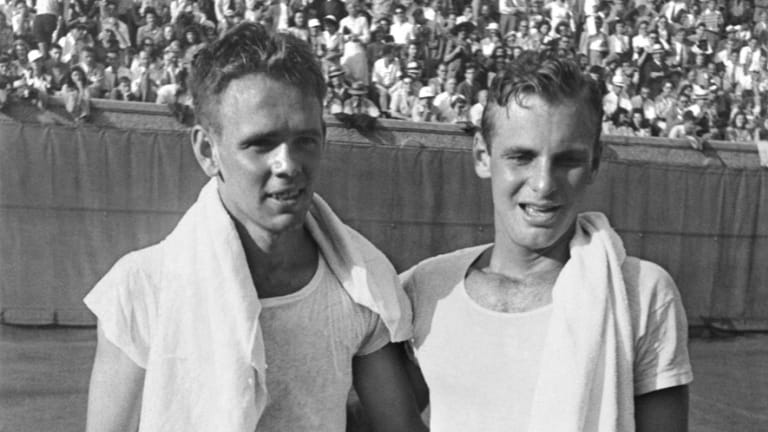

Joe Hunt, 24, and Jack Kramer, 22, certainly fit that depiction as they strode side by side into the stadium at the West Side Tennis Club on that warm, late-summer day. Both men were lean and rangy 6-footers. Both were entering their athletic primes. Both were outfitted in casually utilitarian T-shirts and shorts, rather than the white flannel slacks that had long been the standard uniform among the men. Both played a newfangled style of net-rushing tennis—then known as the Big Game, now known as serve-and-volley—that they had pioneered on hard courts out west. And before their warm-up began, both flashed their toothy California smiles for the camera, as if they expected that the best years of their lives, and the best years of their friendly rivalry, were still to come.

A Tale of Two Soldiers, and Tennis Players: Jack Kramer and Joe Hunt

Advertising

“Strapping blond Californians of serve-and-volley persuasion.” That’s how one tennis historian described the two players who faced off in the final of the U.S. Nationals at Forest Hills in 1943.

Joe Hunt, 24, and Jack Kramer, 22, certainly fit that depiction as they strode side by side into the stadium at the West Side Tennis Club on that warm, late-summer day. Both men were lean and rangy 6-footers. Both were entering their athletic primes. Both were outfitted in casually utilitarian T-shirts and shorts, rather than the white flannel slacks that had long been the standard uniform among the men. Both played a newfangled style of net-rushing tennis—then known as the Big Game, now known as serve-and-volley—that they had pioneered on hard courts out west. And before their warm-up began, both flashed their toothy California smiles for the camera, as if they expected that the best years of their lives, and the best years of their friendly rivalry, were still to come.

A Tale of Two Soldiers, and Tennis Players: Jack Kramer and Joe Hunt

Advertising

Kramer (at left) and Hunt. (Photo courtesy of Joseph Hunt)

But these two all-American young men had something else in common: They were active-duty servicemen on leave from the war that had been raging across the globe for the last four years. Hunt was a graduate of the Naval Academy in Annapolis; he had served as a lieutenant on a destroyer in the Pacific and would do another tour of duty in the Atlantic, before training to become a pilot. Kramer had also tried to become a Navy aviator, but had been turned down because he had 20/30 vision in one eye. Instead, he signed up for the Coast Guard—“anything to escape the infantry”—and would see action in the Pacific during General Douglas MacArthur’s campaign to liberate the Philippines in 1944 and 1945.

The war that Hunt and Kramer were fighting had brought international tennis to a standstill. By 1943, with the sport’s other three major events cancelled, Forest Hills was the only place in the world where players could prove themselves at the Grand Slam level. Wimbledon’s Centre Court had been bombed and wouldn’t be fully repaired until 1950; Roland Garros had been turned into an internment camp; and the Australian Championships was on hiatus while the country’s troops fought in Europe and the Pacific. The United States was also involved in those theaters, of course, but its national tennis championships had been allowed to continue. The Roosevelt administration saw sports as a morale booster.

“We will gladly eliminate tennis if it interferes with winning the war,” USLTA president Holcombe Ward said in 1942. “But our government doesn’t want us to abandon tennis.”

What the U.S. government did want was for its tennis players to do their part in the war effort. Hunt and Kramer joined a long list of top male players—Bobby Riggs, Ted Schroeder, Frank Parker, Wilmer Allison, Gardner Mulloy, Budge Patty, among others—who held military commissions during World War II. At Forest Hills in 1943, five of the eight quarterfinalists were U.S. soldiers. Their service would help legitimate tennis in the eyes of red-blooded American sports fans, many of whom considered the game little more than a polite pastime for the private-club set.

Allison Danzig, sports columnist for The New York Times, wrote of the players’ war contribution, “It’s enough to show that, despite their lip service to the social amenities, the boys in the ice-cream pants aren’t any comfort to Tojo or Adolf.”

While Hunt and Kramer began the ’43 final as happy warrior-athletes, their match would slowly devolve into a battle of the walking wounded. A few days earlier, Kramer had eaten some “bad clams” at a New York restaurant, and after surviving his semifinal with Pancho Segura, he spent the previous day in bed. “But it just wasn’t enough to get all the poison out of my system,” he said.

Still, Kramer hoped he could “sneak by” Hunt; after all, he had been beating him in practice back home in Los Angeles. For a couple of hours, it appeared as if his luck might hold. The two men split the first two sets, and Kramer served for the third at 5-4. That’s when Hunt made his stand. He broke serve with what Kramer called a “fine defensive effort” and captured the crucial set 10-8. Kramer had nothing left. At the start of the tournament he had weighed 168 pounds; by the time it was over, he was a much-stringier 149.

But something unexpected happened on the way to Hunt’s coronation as the new king of U.S. tennis: he started to cramp. Even as he was building a seemingly insurmountable lead in the fourth set, he was limping from one point to the next. When Kramer served at 0-5, both men looked as if they were struggling to stay on their feet. If Kramer could hang on long enough, could he win by default? Hunt reached double match point at 15-40, and managed to put his return in the middle of the court. As Kramer moved forward to hit a forehand, Hunt shuffled unsteadily across his baseline. The ball flew off Kramer’s strings and sailed toward Hunt. It would only become apparent after it landed how close both men had been to victory, and to defeat.

Kramer and Hunt had come a long way since they had first encountered each other at a junior tournament in California eight years earlier. That had been in Santa Monica in 1935, at an event called the Dudley Cup, which also happened to be the first tournament that the 13-year-old Kramer had entered. While the newbie made an unceremoniously quick exit in the first round, he never forgot his early glimpses of Hunt, and the (incredibly strong) local competition.

“Up until that point I knew nothing about tennis,” Kramer recalled. “I showed up at that first tournament in a brown mohair sweater. It was like another world. The other kids all had on perfect tennis whites, Tilden V-neck sweaters, and they all carried two or three shiny new racquets. Little Bobby Riggs was there. Little Joe Hunt, little Ted Schroeder. Throw in the unknown little Jack Kramer and there were four boys who would win six U.S. Nationals titles [at Forest Hills] in the next dozen years.”

Kramer didn’t come from a tennis family, or a country-club family. His father, David, worked his entire life as a brakeman for the Union Pacific Railroad, starting at age 11. But he was determined to give his son a chance to play the games he never had time to play. David introduced Jack to baseball, football and basketball; used the dinning room table for ping-pong matches; and even dug his son a pole-vault and long-jump pit in the backyard. Jack initially gravitated toward baseball, but one weekend he happened to see world No. 1 Ellsworth Vines play an exhibition match at a nearby county fair. Kramer was hooked.

“There I was that day in 1935: 13 years old, a poor kid from the desert,” Kramer said. “And here’s Ellsworth Vines, 6’2”, 155 pounds, dressed like Fred Astaire and hitting shots like Babe Ruth. I never again concentrated on any sport but tennis.”

While Kramer’s father didn’t expect his son to get rich playing the game, he moved the family from Las Vegas to Montebello, east of L.A., because he thought it would be better for Jack’s tennis. David had no idea how right he would turn out to be. Los Angeles in the 1930s was in the process of becoming the world’s greatest incubator of tennis talent, and Jack would take his place at the forefront of a wave of young champions from the area who would dominate the sport, and change how it was played, in the coming decades.

Advertising

A Tale of Two Soldiers, and Tennis Players: Jack Kramer and Joe Hunt

California had been churning out top tennis talent for years, of course, but most of the early stars had come from the Bay Area—Helen Wills, Maurice McLoughlin, Bill Johnston, Helen Hull Jacobs, Margaret Osborne Dupont and Don Budge included. With Vines (pictured at right, from Wikimedia Commons), the balance of power began to shift south, to a band of Depression-era kids who learned the game on public hard courts, rather than at private clubs. The 13-year-old Kramer may not have succeeded in winning a match at the Dudley Cup, but he walked away with something more important: a recommendation.

“Before I left Santa Monica, stunned and beaten, someone kind suggested I see a man named Perry Jones at the Los Angeles Tennis Club,” Kramer remembered. “Jones, of course, ran the Southern California Tennis Association. He was ‘Mister Jones’ if you wanted to go anywhere.”

Perry Jones was the persnickety majordomo of SoCal tennis, and he liked his players to look like they could have come from central casting down the road in Hollywood. The 6’2” Kramer became one of his favorites. Through Jones, Kramer gained entree to the Southern California junior elite, and soon found himself playing at The Los Angeles Tennis Club on a daily basis, competing against older players and future Hall-of-Famers like Vines, Riggs, Hunt, Schroeder, Gene Mako, Sidney Wood, Frank Shields, Bill Tilden and later, Pancho Gonzalez. A tennis academy before the word was invented, the LATC gave this budding Greatest Generation of U.S. tennis a place where they could push each other, and find new ways to win.

“The L.A. Tennis Club was like a laboratory,” said Kramer, whose father arranged his schedule so he could take his classes in the morning and be free to play tennis all afternoon. The person that Jack experimented with most wasn’t one of his junior rivals, though; it was a 45-year-old hydraulic engineer and club player named Cliff Roche. “Coach,” as Kramer called him, brought a gambler’s mentality to the game that suited the young Las Vegas native.

“He showed me that the odds on a court could be the same as with a deck of 52,” Kramer said. “Put the ball in a certain spot, and put yourself in a certain spot, and the chance of the other player getting out of that spot would be the same as drawing a third king.”

Roche was an early adherent of what became known as “percentage tennis.” He emphasized taking the ball on the rise, rushing the net, and, most of all, holding onto your serve. Many of today’s tennis truisms echo Roche’s philosophy: “You’re only as good as your second serve”; “you can’t lose if you’re never broken”; “break down the other guy’s strength”; “make your opponent come up with a perfect passing shot to beat you.”

If Roche was responsible for the theories behind percentage tennis, it took Kramer and his powerful serve-and-volley attack to turn it into the Big Game. In 1938, just a few years after taking up tennis seriously, he won the National Interscholastics; in 1940 he reached the semifinals at Forest Hills. And in 1939, at 18, he became the youngest man to play in a Davis Cup final, a record he would hold for 29 years.

Advertising

A Tale of Two Soldiers, and Tennis Players: Jack Kramer and Joe Hunt

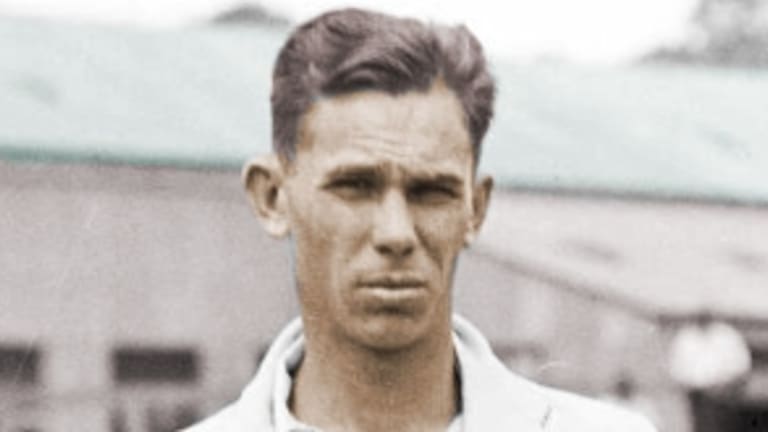

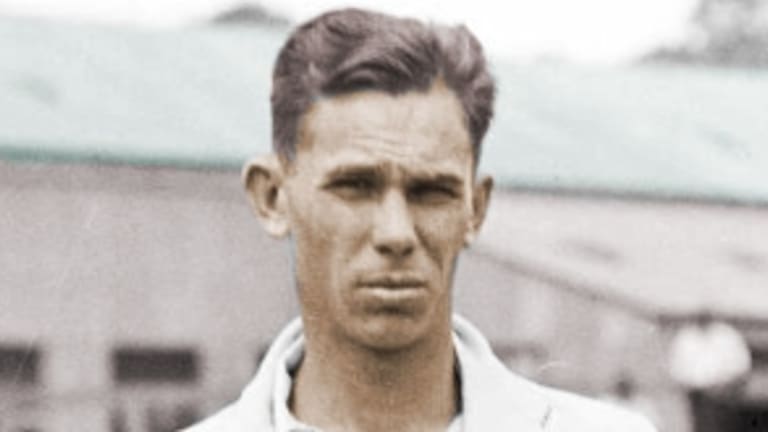

Jack Kramer. (Wikimedia Commons)

That August, Kramer traveled to the Merion Cricket Club in Pennsylvania, where the Challenge Round against Australia would be staged. After much discussion, he was picked to play the doubles rubber. His partner would be Joe Hunt. During the match, which the two Californians would lose to the best team in the world at the time, John Bromwich and Adrian Quist, the fans at Merion began to see newsboys circling the stands and calling out “Extra!” When the players took a break to switch sides, many spectators ran out to buy papers from them. Reading the headlines, they learned that Great Britain had declared war on Germany.

“It was September 3rd, 1939,” Kramer said. “Outside, the world was falling apart and I was too young and naive to know. Hitler was marching into Poland.”

The Australians, who now represented a country that was officially at war, beat the Americans the following day. The Davis Cup wouldn’t be held again until 1946. But more important duties lay ahead for the U.S. team's young doubles partners.

Advertising

“Joe was something of a hero of mine,” Kramer wrote of Hunt in his autobiography, The Game. “He had always been very kind about playing me good practice matches when I was still only 15 or 16.”

Kramer, forever the kid in the mohair sweater, liked something else about Hunt: “He had beautiful equipment.”

If you wanted to idolize a tennis player—in the 1930s or the 2020s, for that matter—you could do worse than to choose Joe Hunt. Blond-haired, powerfully built, 6-feet tall, friendly and easygoing, he personified the California athletic ideal, as well as the the ideal of the tennis player as a sporting gentleman.

“He was a very good-looking man with a body like Charles Atlas,” Segura told USA Today in 2014. “He drew women to his matches. He would have been good for tennis. He was a credit to the game.”

“He was a carefree, energetic person,” says Joseph Hunt, a grand-nephew of Hunt’s who is an attorney in Seattle. “Bobby Riggs talked about what a fun-loving person he was, and about their friendship. Joe was already known for his big smile when he was two weeks old.”

Unlike Kramer, Hunt very much did come from a tennis family. His father, Reuben, a bankruptcy lawyer who had been a high-level player in Canada and won a few few rounds at the U.S. Nationals in Newport, introduced his three children to the game. Joe began playing at 5, and was winning tournaments before he turned 10.

The Hunt family embodied the southward shift in California tennis in the 1930s. Reuben played for Cal-Berkeley at the turn of the century, and Joe was born in San Francisco. But his game was formed alongside the rest of Perry Jones’ boys at the Los Angeles Tennis Club. Like many of them, he began his college career at USC. In 1938, Hunt won the NCAA doubles title with SC teammate Lewis Wetherell.

“He was an excellent prospect from a very young age,” Kramer said. “He succeeded Riggs as the outstanding junior in Southern California.”

While Kramer has always been credited with pioneering the Big Game, Hunt was every bit as committed to the attacking style.

“He was total total serve and volley, he came to the net on first and second serves,” Joseph Hunt says. “When you read articles from that time, you see Joe described as the best volleyer in the U.S.”

Reuben Hunt dreamed of seeing his son become the world’s best tennis player, and by 1938, Joe seemed to be well on his way to fulfilling that dream. But as signs of war became harder to ignore, he found his desire to serve his country harder to ignore as well. On a trip to play the Sugar Bowl in New Orleans during his sophomore year, Hunt met a player from Navy. As they talked, he grew interested in the Naval Academy, and decided to visit Annapolis.

“That visit changed his life,” Joseph Hunt says. “He never told his family about it. There was a lot of pressure on him to keep going as he was and become the No. 1 tennis player.”

Monday, September 7 is Lt. Joe Hunt US Open Military Appreciation Day:

A Tale of Two Soldiers, and Tennis Players: Jack Kramer and Joe Hunt

Advertising

Instead, Hunt transferred from USC, a hotbed for tennis, to the Naval Academy, which had never produced a top-level player. Then he did something even more unheard of for a budding tennis star: He went out for the football team. Hunt played halfback, and while he made the varsity, he spent most of his time on the bench.

“He was roughed around by football,” his grand nephew says. But Hunt’s teammates loved him, and he loved them, as well as the camaraderie the sport offered. In 1941, Hunt skipped Forest Hills, where he would would have been among the favorites for the title, to play the Army-Navy football game. In appreciation of the sacrifice, his teammates signed the game ball and gave it to him afterward.

Whatever lumps Hunt took on the football field, they didn’t slow him down on the tennis court. He reached the quarterfinals at Forest Hills in 1938, and the semis in ’39 and ’40. In 1941 he became the only man from Navy ever to win the NCAA singles championship. By 1939, Hunt’s tennis skills were deemed essential enough to have him excused from a Naval Academy training cruise so he could play the Davis Cup Challenge Round against Australia. This didn’t sit well with at least one columnist.

“The fact that Hunt has a good forehand and a strong net attack seems a ridiculous reason to excuse him,” Henry McLemore of UPI wrote. But excused Hunt was, and he joined Kramer in the U.S. team's ill-fated mission against the Aussies at Merion.

As we’ve seen, by the time that tie was over, war in Europe had become a reality. Two years later, war in the Pacific would as well. Hunt was scheduled to graduate from the Naval Academy in the spring of 1942, but with the conflict looming, his class’ commencement was moved up. In December ’41, after Pearl Harbor, the U.S. declared war on Japan, and Hunt was called to serve on a destroyer in San Diego.

“Is this the end of the Forest Hills dream?” he may have wondered. He also may have wondered how long there would be a Forest Hills to play.

Jack Kramer had his own Forest Hills dreams, but before he could fulfill them he had to endure what may have been the most prolonged period of bad luck at the Grand Slams of any great player.

At Wimbledon, Kramer likely would have been favored to win the title every year from 1942 to 1945, if the tournament hadn’t been cancelled due to the war. When the event returned in ’46, Kramer was seeded second, but a blister forced him to wear a glove on his playing hand, and contributed to his fourth-round defeat. Finally, in ’47, as the top seed, he stayed healthy and dropped just one set on his way to his only Wimbledon title.

The U.S. Nationals, as we’ve seen, went on during the war, but Kramer’s karma was just as bad in New York. In 1942, he had appendicitis. In 1943, he ate those bad clams. In 1944 and 1945, he was thousands of miles away on a ship in the Pacific. It wasn’t until 1946 that he won his first Forest Hills. But his reign, like most reigns in the amateur era, was brief. After repeating as national champion in 1947, he turned pro and was banned from Forest Hills for the rest of his playing days.

Like many champions, though, Kramer had a way of finding silver linings in his defeats and frustrations. Looking back on his career in the late 1970s, he said he felt “lucky to get appendicitis in ’42 and clam poisoning in ’43.” If he had won the country’s national championship, he believed, the military would have made him a “poster boy.”

“The Coast Guard would have put me in special services, and I would have spent the war playing tennis entertaining the troops,” Kramer reflected.

Instead, Kramer was sent into battle and forced to grow up fast. In March 1944, he was commissioned as an officer and shipped into action on an LST (landing ship/tank) with the Seventh Fleet. There was plenty of action to be had in the Pacific at that time. He made seven landings as a supply officer. The most significant came during the Battle of Leyte Gulf, which launched MacArthur’s successful campaign to reclaim the Philippines from the Japanese. With 200,000 personnel involved, it was the largest naval conflict of World War II. Three days in, MacArthur made his famous walk through the waves and onto the sands at Leyte’s Red Beach, but fighting would continue there until the following spring.

“I was in some real shooting,” Kramer said. “I was in the war.”

Yet it was Kramer’s time alone on the ship and away from combat that would mean the most to him and his career. “I had a lot of time to think,” he said of the hours he spent on his LST’s overnight watch. While his fellow soldiers slept, he reassessed how he wanted to live his life.

“The young man on night watch in the Pacific, gazing at the moonlit sea and planning his postwar life, is a classic figure of World War II,” Sports Illustrated’s Dick Phelan wrote in a 1958 profile of Kramer. “Of all the young men who did it, perhaps none saw his future work out more precisely to specifications than Lieutenant [Jack] Kramer.”

Kramer decided that the game had come too naturally for him, and that he had let himself “drift.” He realized he had thrown away his chance at getting an education, and that his choices would be limited when he came home. “If I didn’t make it with tennis,” said Kramer, who had married his wife, Gloria, just before shipping out, “I was going to end up pumping gas somewhere.”

“I sat out on that old LST,” Kramer told Phelan, “and I did some serious thinking. No more gambling, no more staying up late, no drinking…I decided to go all out for a few major tournaments in 1946. It worked out like a dream.”

Advertising

Kramer won titles at Wimbledon and Forest Hills immediately after the war. In 1948, he turned pro and was guaranteed $50,000 for a tour with Riggs. By then he was ready for the big leagues. He won the tour, 69 matches to 20, and became the top professional. He continued in tennis as a player, promoter, tournament director, broadcaster—and eventual bête noire of Billie Jean King—for the next 40 years. His signature Wilson racquets were among the most popular in the game’s history. He never had to pump gas.

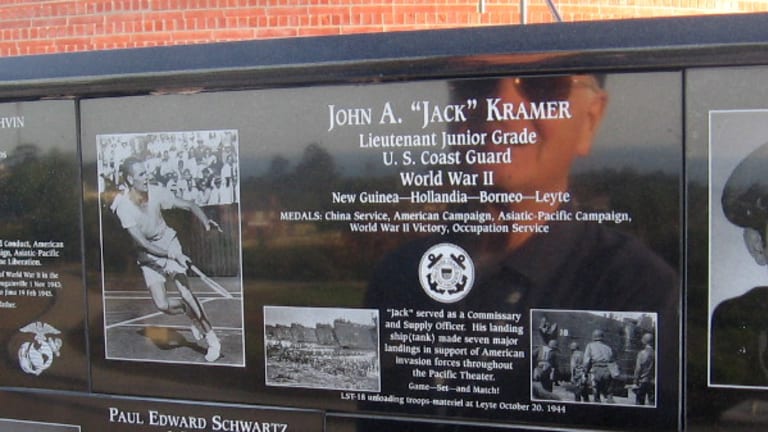

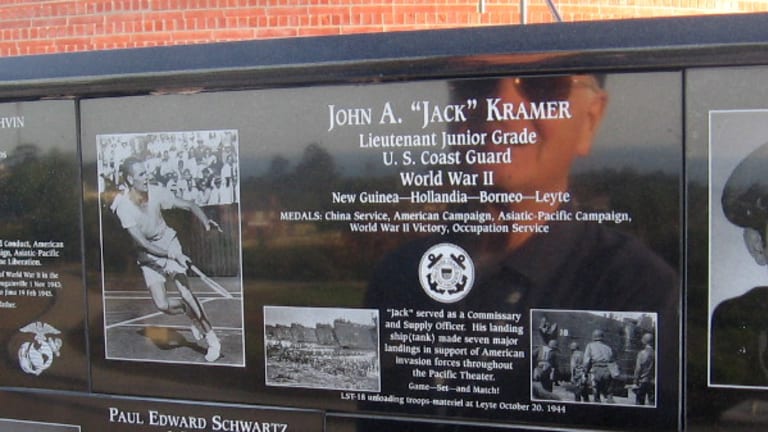

After the war, he and Gloria had five sons. One of them, Bob, continued his father’s legacy as an L.A.-area tournament director, and also served as a Navy pilot. A few years ago, Bob joined his family in dedicating a plaque at the Mount Soledad Veterans Memorial in La Jolla, Calif., commemorating Jack’s war service. On the plaque (pictured below) is a brief history of his Pacific landings, and the medals he won.

Advertising

A Tale of Two Soldiers, and Tennis Players: Jack Kramer and Joe Hunt

This history, and these honors, weren’t news to Bob, exactly, but they also weren’t things that his father had often brought up or lingered over.

“You know those greatest generation guys,” Bob Kramer says. “They didn’t like to talk about the war. I think they were happy it was over.”

Advertising

Joe Hunt, it seemed, wanted to do as much he could before the conflict came to an end.

As a college student, he had left the sunny sporting life of Southern California to sign up at the Naval Academy and throw himself into the country’s upcoming war effort. Once he graduated, Hunt was sent back to California, where he spent two years on a destroyer, the USS Rathburne, in San Diego and the Pacific. After being granted leave to play at Forest Hills in 1943, he was sent in the other direction, to serve in the Atlantic. Still, it wasn’t enough.

“Joe got the bug to be a flier,” his friend and New York Times reporter Allison Danzig wrote. “Some tried to discourage him, but he made up his mind. It wasn’t alone the glamour and thrill of being a fighter pilot that appealed to him. Aviation, he decided, was to be the next big thing in the future and he wanted in on it.”

In late 1943, Hunt applied for a transfer to the Navy Air Force, and, with his wife, Jacque (who was also a very good tennis player), traveled first to a training center in Dallas, and then to a base in Pensacola, Fla. There he met up with fellow player and pilot Ted Schroeder, who had won at Forest Hills in 1942. Unable to secure leave for the 1944 U.S. Nationals, Hunt and Schroeder staged their own, two-man U.S. championships at the Bayview Park Center in Pensacola that year. A huge crowd came out to see the last two Forest Hills winners take each other on. Hunt would beat Schroeder in what would be the last tennis match of his life.

Soon after, Hunt was transferred to Daytona for flight training. It was there that on February 2, 1945, he went up to 10,000 feet in a Grumman Hellcat fighter plane for a target run. Normally, the pilot would dive to 4,000 feet and then pull out, and that’s what Hunt’s instructors told him to do over the plane’s radio. But the aircraft went into a spin instead, and ended up in the ocean. By the time rescue boats reached the crash spot, it had sunk. Only pieces of it would be found.

“Nobody really knows what happened,” Joseph Hunt says. “It was determined that there was no pilot error, but there could have been something wrong with the plane, or the life raft may have inflated accidentally. He could have blacked out from the G force.”

Two weeks shy of his 26th birthday, Hunt was dead. American Lawn Tennis Magazine put a photo of Hunt in his plane on its next cover, and Danzig paid tribute in the New York Times.

“Fame did not go to his head. He was serious in his outlook, but did not take himself or his position in tennis that way….He did the right and fair thing instinctively.”

“Joe was every inch the ideal of what every parent would like his son to be,” Danzig concluded. “He was fine all the way through. Tennis isn’t going to be the same without him.”

Hunt’s training class would graduate in July 1945. As the young pilots waited to be called up and given their assignments, the U.S. dropped atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki and essentially ended the war.

“He may never have had to go,” Joseph Hunt says.

Kramer and Hunt believed their 1943 final at Forest Hills was just the beginning for them. Surely they would vie for more major titles, and team up to bring the Davis Cup home. Surely, they would put on finer performances than this match between a man with food poisoning and another with a cramp. As it was, it would be their last meeting. But while it wasn’t the greatest final in Forest Hills history, it had one of the most memorable conclusions.

Serving at 0-5, 15-40 in the fourth set, Kramer hit a mid-court forehand and moved toward the net. Before he made it there, though, his approach shot landed long, and the match was over. Rather than lifting his arms in celebration, Hunt, who had been nursing a leg cramp for the better of the fourth set, collapsed and couldn’t get up. Kramer walked across the court to make sure his friend was OK.

“There I was, the loser, standing up dead on my feet while he was the winner, fallen in a heap,” Kramer said. “If I’d kept that ball in the court, I think I would have been the champ by default.”

Instead, Kramer sat down on the grass and, one soldier-player to another, shook Hunt’s hand in congratulation.

Advertising

A Tale of Two Soldiers, and Tennis Players: Jack Kramer and Joe Hunt

Kramer and Hunt, just after their match at Forest Hills. (International Tennis Hall of Fame)

Advertising

Three decades later, in the early 1970s, a young Joseph Hunt—Joe’s grand-nephew and namesake—attended the Pacific Southwest Championships, the tournament that Kramer ran at the Los Angeles Tennis Club.

“I saw Jack there, and somebody in my family said, ‘You have to go meet him,’” Hunt says. “So I introduced myself, and he said, ‘Are you related to THE Joe Hunt?’ He invited me over to sit with him and talk. He said, ‘When Joe died, I lost my greatest rival.’”

“Jack talked about how he and Joe had been Davis Cup partners, but you know what he never mentioned?” Hunt continues with a laugh. “Their Forest Hills match.”

“I think Jack still wanted that last forehand back.”

Advertising

A Tale of Two Soldiers, and Tennis Players: Jack Kramer and Joe Hunt

Kramer (at left) and Hunt. (Photo courtesy of Joseph Hunt)

But these two all-American young men had something else in common: They were active-duty servicemen on leave from the war that had been raging across the globe for the last four years. Hunt was a graduate of the Naval Academy in Annapolis; he had served as a lieutenant on a destroyer in the Pacific and would do another tour of duty in the Atlantic, before training to become a pilot. Kramer had also tried to become a Navy aviator, but had been turned down because he had 20/30 vision in one eye. Instead, he signed up for the Coast Guard—“anything to escape the infantry”—and would see action in the Pacific during General Douglas MacArthur’s campaign to liberate the Philippines in 1944 and 1945.

The war that Hunt and Kramer were fighting had brought international tennis to a standstill. By 1943, with the sport’s other three major events cancelled, Forest Hills was the only place in the world where players could prove themselves at the Grand Slam level. Wimbledon’s Centre Court had been bombed and wouldn’t be fully repaired until 1950; Roland Garros had been turned into an internment camp; and the Australian Championships was on hiatus while the country’s troops fought in Europe and the Pacific. The United States was also involved in those theaters, of course, but its national tennis championships had been allowed to continue. The Roosevelt administration saw sports as a morale booster.

“We will gladly eliminate tennis if it interferes with winning the war,” USLTA president Holcombe Ward said in 1942. “But our government doesn’t want us to abandon tennis.”

What the U.S. government did want was for its tennis players to do their part in the war effort. Hunt and Kramer joined a long list of top male players—Bobby Riggs, Ted Schroeder, Frank Parker, Wilmer Allison, Gardner Mulloy, Budge Patty, among others—who held military commissions during World War II. At Forest Hills in 1943, five of the eight quarterfinalists were U.S. soldiers. Their service would help legitimate tennis in the eyes of red-blooded American sports fans, many of whom considered the game little more than a polite pastime for the private-club set.

Allison Danzig, sports columnist for The New York Times, wrote of the players’ war contribution, “It’s enough to show that, despite their lip service to the social amenities, the boys in the ice-cream pants aren’t any comfort to Tojo or Adolf.”

While Hunt and Kramer began the ’43 final as happy warrior-athletes, their match would slowly devolve into a battle of the walking wounded. A few days earlier, Kramer had eaten some “bad clams” at a New York restaurant, and after surviving his semifinal with Pancho Segura, he spent the previous day in bed. “But it just wasn’t enough to get all the poison out of my system,” he said.

Still, Kramer hoped he could “sneak by” Hunt; after all, he had been beating him in practice back home in Los Angeles. For a couple of hours, it appeared as if his luck might hold. The two men split the first two sets, and Kramer served for the third at 5-4. That’s when Hunt made his stand. He broke serve with what Kramer called a “fine defensive effort” and captured the crucial set 10-8. Kramer had nothing left. At the start of the tournament he had weighed 168 pounds; by the time it was over, he was a much-stringier 149.

But something unexpected happened on the way to Hunt’s coronation as the new king of U.S. tennis: he started to cramp. Even as he was building a seemingly insurmountable lead in the fourth set, he was limping from one point to the next. When Kramer served at 0-5, both men looked as if they were struggling to stay on their feet. If Kramer could hang on long enough, could he win by default? Hunt reached double match point at 15-40, and managed to put his return in the middle of the court. As Kramer moved forward to hit a forehand, Hunt shuffled unsteadily across his baseline. The ball flew off Kramer’s strings and sailed toward Hunt. It would only become apparent after it landed how close both men had been to victory, and to defeat.

Advertising

Kramer and Hunt had come a long way since they had first encountered each other at a junior tournament in California eight years earlier. That had been in Santa Monica in 1935, at an event called the Dudley Cup, which also happened to be the first tournament that the 13-year-old Kramer had entered. While the newbie made an unceremoniously quick exit in the first round, he never forgot his early glimpses of Hunt, and the (incredibly strong) local competition.

“Up until that point I knew nothing about tennis,” Kramer recalled. “I showed up at that first tournament in a brown mohair sweater. It was like another world. The other kids all had on perfect tennis whites, Tilden V-neck sweaters, and they all carried two or three shiny new racquets. Little Bobby Riggs was there. Little Joe Hunt, little Ted Schroeder. Throw in the unknown little Jack Kramer and there were four boys who would win six U.S. Nationals titles [at Forest Hills] in the next dozen years.”

Kramer didn’t come from a tennis family, or a country-club family. His father, David, worked his entire life as a brakeman for the Union Pacific Railroad, starting at age 11. But he was determined to give his son a chance to play the games he never had time to play. David introduced Jack to baseball, football and basketball; used the dinning room table for ping-pong matches; and even dug his son a pole-vault and long-jump pit in the backyard. Jack initially gravitated toward baseball, but one weekend he happened to see world No. 1 Ellsworth Vines play an exhibition match at a nearby county fair. Kramer was hooked.

“There I was that day in 1935: 13 years old, a poor kid from the desert,” Kramer said. “And here’s Ellsworth Vines, 6’2”, 155 pounds, dressed like Fred Astaire and hitting shots like Babe Ruth. I never again concentrated on any sport but tennis.”

While Kramer’s father didn’t expect his son to get rich playing the game, he moved the family from Las Vegas to Montebello, east of L.A., because he thought it would be better for Jack’s tennis. David had no idea how right he would turn out to be. Los Angeles in the 1930s was in the process of becoming the world’s greatest incubator of tennis talent, and Jack would take his place at the forefront of a wave of young champions from the area who would dominate the sport, and change how it was played, in the coming decades.

A Tale of Two Soldiers, and Tennis Players: Jack Kramer and Joe Hunt

Advertising

California had been churning out top tennis talent for years, of course, but most of the early stars had come from the Bay Area—Helen Wills, Maurice McLoughlin, Bill Johnston, Helen Hull Jacobs, Margaret Osborne Dupont and Don Budge included. With Vines (pictured at right, from Wikimedia Commons), the balance of power began to shift south, to a band of Depression-era kids who learned the game on public hard courts, rather than at private clubs. The 13-year-old Kramer may not have succeeded in winning a match at the Dudley Cup, but he walked away with something more important: a recommendation.

“Before I left Santa Monica, stunned and beaten, someone kind suggested I see a man named Perry Jones at the Los Angeles Tennis Club,” Kramer remembered. “Jones, of course, ran the Southern California Tennis Association. He was ‘Mister Jones’ if you wanted to go anywhere.”

Perry Jones was the persnickety majordomo of SoCal tennis, and he liked his players to look like they could have come from central casting down the road in Hollywood. The 6’2” Kramer became one of his favorites. Through Jones, Kramer gained entree to the Southern California junior elite, and soon found himself playing at The Los Angeles Tennis Club on a daily basis, competing against older players and future Hall-of-Famers like Vines, Riggs, Hunt, Schroeder, Gene Mako, Sidney Wood, Frank Shields, Bill Tilden and later, Pancho Gonzalez. A tennis academy before the word was invented, the LATC gave this budding Greatest Generation of U.S. tennis a place where they could push each other, and find new ways to win.

“The L.A. Tennis Club was like a laboratory,” said Kramer, whose father arranged his schedule so he could take his classes in the morning and be free to play tennis all afternoon. The person that Jack experimented with most wasn’t one of his junior rivals, though; it was a 45-year-old hydraulic engineer and club player named Cliff Roche. “Coach,” as Kramer called him, brought a gambler’s mentality to the game that suited the young Las Vegas native.

“He showed me that the odds on a court could be the same as with a deck of 52,” Kramer said. “Put the ball in a certain spot, and put yourself in a certain spot, and the chance of the other player getting out of that spot would be the same as drawing a third king.”

Roche was an early adherent of what became known as “percentage tennis.” He emphasized taking the ball on the rise, rushing the net, and, most of all, holding onto your serve. Many of today’s tennis truisms echo Roche’s philosophy: “You’re only as good as your second serve”; “you can’t lose if you’re never broken”; “break down the other guy’s strength”; “make your opponent come up with a perfect passing shot to beat you.”

If Roche was responsible for the theories behind percentage tennis, it took Kramer and his powerful serve-and-volley attack to turn it into the Big Game. In 1938, just a few years after taking up tennis seriously, he won the National Interscholastics; in 1940 he reached the semifinals at Forest Hills. And in 1939, at 18, he became the youngest man to play in a Davis Cup final, a record he would hold for 29 years.

A Tale of Two Soldiers, and Tennis Players: Jack Kramer and Joe Hunt

Advertising

Jack Kramer. (Wikimedia Commons)

That August, Kramer traveled to the Merion Cricket Club in Pennsylvania, where the Challenge Round against Australia would be staged. After much discussion, he was picked to play the doubles rubber. His partner would be Joe Hunt. During the match, which the two Californians would lose to the best team in the world at the time, John Bromwich and Adrian Quist, the fans at Merion began to see newsboys circling the stands and calling out “Extra!” When the players took a break to switch sides, many spectators ran out to buy papers from them. Reading the headlines, they learned that Great Britain had declared war on Germany.

“It was September 3rd, 1939,” Kramer said. “Outside, the world was falling apart and I was too young and naive to know. Hitler was marching into Poland.”

The Australians, who now represented a country that was officially at war, beat the Americans the following day. The Davis Cup wouldn’t be held again until 1946. But more important duties lay ahead for the U.S. team's young doubles partners.

“Joe was something of a hero of mine,” Kramer wrote of Hunt in his autobiography, The Game. “He had always been very kind about playing me good practice matches when I was still only 15 or 16.”

Kramer, forever the kid in the mohair sweater, liked something else about Hunt: “He had beautiful equipment.”

If you wanted to idolize a tennis player—in the 1930s or the 2020s, for that matter—you could do worse than to choose Joe Hunt. Blond-haired, powerfully built, 6-feet tall, friendly and easygoing, he personified the California athletic ideal, as well as the the ideal of the tennis player as a sporting gentleman.

“He was a very good-looking man with a body like Charles Atlas,” Segura told USA Today in 2014. “He drew women to his matches. He would have been good for tennis. He was a credit to the game.”

“He was a carefree, energetic person,” says Joseph Hunt, a grand-nephew of Hunt’s who is an attorney in Seattle. “Bobby Riggs talked about what a fun-loving person he was, and about their friendship. Joe was already known for his big smile when he was two weeks old.”

Unlike Kramer, Hunt very much did come from a tennis family. His father, Reuben, a bankruptcy lawyer who had been a high-level player in Canada and won a few few rounds at the U.S. Nationals in Newport, introduced his three children to the game. Joe began playing at 5, and was winning tournaments before he turned 10.

The Hunt family embodied the southward shift in California tennis in the 1930s. Reuben played for Cal-Berkeley at the turn of the century, and Joe was born in San Francisco. But his game was formed alongside the rest of Perry Jones’ boys at the Los Angeles Tennis Club. Like many of them, he began his college career at USC. In 1938, Hunt won the NCAA doubles title with SC teammate Lewis Wetherell.

“He was an excellent prospect from a very young age,” Kramer said. “He succeeded Riggs as the outstanding junior in Southern California.”

While Kramer has always been credited with pioneering the Big Game, Hunt was every bit as committed to the attacking style.

“He was total total serve and volley, he came to the net on first and second serves,” Joseph Hunt says. “When you read articles from that time, you see Joe described as the best volleyer in the U.S.”

Reuben Hunt dreamed of seeing his son become the world’s best tennis player, and by 1938, Joe seemed to be well on his way to fulfilling that dream. But as signs of war became harder to ignore, he found his desire to serve his country harder to ignore as well. On a trip to play the Sugar Bowl in New Orleans during his sophomore year, Hunt met a player from Navy. As they talked, he grew interested in the Naval Academy, and decided to visit Annapolis.

“That visit changed his life,” Joseph Hunt says. “He never told his family about it. There was a lot of pressure on him to keep going as he was and become the No. 1 tennis player.”

Monday, September 7 is Lt. Joe Hunt US Open Military Appreciation Day:

Advertising

A Tale of Two Soldiers, and Tennis Players: Jack Kramer and Joe Hunt

Instead, Hunt transferred from USC, a hotbed for tennis, to the Naval Academy, which had never produced a top-level player. Then he did something even more unheard of for a budding tennis star: He went out for the football team. Hunt played halfback, and while he made the varsity, he spent most of his time on the bench.

“He was roughed around by football,” his grand nephew says. But Hunt’s teammates loved him, and he loved them, as well as the camaraderie the sport offered. In 1941, Hunt skipped Forest Hills, where he would would have been among the favorites for the title, to play the Army-Navy football game. In appreciation of the sacrifice, his teammates signed the game ball and gave it to him afterward.

Whatever lumps Hunt took on the football field, they didn’t slow him down on the tennis court. He reached the quarterfinals at Forest Hills in 1938, and the semis in ’39 and ’40. In 1941 he became the only man from Navy ever to win the NCAA singles championship. By 1939, Hunt’s tennis skills were deemed essential enough to have him excused from a Naval Academy training cruise so he could play the Davis Cup Challenge Round against Australia. This didn’t sit well with at least one columnist.

“The fact that Hunt has a good forehand and a strong net attack seems a ridiculous reason to excuse him,” Henry McLemore of UPI wrote. But excused Hunt was, and he joined Kramer in the U.S. team's ill-fated mission against the Aussies at Merion.

As we’ve seen, by the time that tie was over, war in Europe had become a reality. Two years later, war in the Pacific would as well. Hunt was scheduled to graduate from the Naval Academy in the spring of 1942, but with the conflict looming, his class’ commencement was moved up. In December ’41, after Pearl Harbor, the U.S. declared war on Japan, and Hunt was called to serve on a destroyer in San Diego.

“Is this the end of the Forest Hills dream?” he may have wondered. He also may have wondered how long there would be a Forest Hills to play.

Advertising

Jack Kramer had his own Forest Hills dreams, but before he could fulfill them he had to endure what may have been the most prolonged period of bad luck at the Grand Slams of any great player.

At Wimbledon, Kramer likely would have been favored to win the title every year from 1942 to 1945, if the tournament hadn’t been cancelled due to the war. When the event returned in ’46, Kramer was seeded second, but a blister forced him to wear a glove on his playing hand, and contributed to his fourth-round defeat. Finally, in ’47, as the top seed, he stayed healthy and dropped just one set on his way to his only Wimbledon title.

The U.S. Nationals, as we’ve seen, went on during the war, but Kramer’s karma was just as bad in New York. In 1942, he had appendicitis. In 1943, he ate those bad clams. In 1944 and 1945, he was thousands of miles away on a ship in the Pacific. It wasn’t until 1946 that he won his first Forest Hills. But his reign, like most reigns in the amateur era, was brief. After repeating as national champion in 1947, he turned pro and was banned from Forest Hills for the rest of his playing days.

Like many champions, though, Kramer had a way of finding silver linings in his defeats and frustrations. Looking back on his career in the late 1970s, he said he felt “lucky to get appendicitis in ’42 and clam poisoning in ’43.” If he had won the country’s national championship, he believed, the military would have made him a “poster boy.”

“The Coast Guard would have put me in special services, and I would have spent the war playing tennis entertaining the troops,” Kramer reflected.

Instead, Kramer was sent into battle and forced to grow up fast. In March 1944, he was commissioned as an officer and shipped into action on an LST (landing ship/tank) with the Seventh Fleet. There was plenty of action to be had in the Pacific at that time. He made seven landings as a supply officer. The most significant came during the Battle of Leyte Gulf, which launched MacArthur’s successful campaign to reclaim the Philippines from the Japanese. With 200,000 personnel involved, it was the largest naval conflict of World War II. Three days in, MacArthur made his famous walk through the waves and onto the sands at Leyte’s Red Beach, but fighting would continue there until the following spring.

“I was in some real shooting,” Kramer said. “I was in the war.”

Yet it was Kramer’s time alone on the ship and away from combat that would mean the most to him and his career. “I had a lot of time to think,” he said of the hours he spent on his LST’s overnight watch. While his fellow soldiers slept, he reassessed how he wanted to live his life.

“The young man on night watch in the Pacific, gazing at the moonlit sea and planning his postwar life, is a classic figure of World War II,” Sports Illustrated’s Dick Phelan wrote in a 1958 profile of Kramer. “Of all the young men who did it, perhaps none saw his future work out more precisely to specifications than Lieutenant [Jack] Kramer.”

Kramer decided that the game had come too naturally for him, and that he had let himself “drift.” He realized he had thrown away his chance at getting an education, and that his choices would be limited when he came home. “If I didn’t make it with tennis,” said Kramer, who had married his wife, Gloria, just before shipping out, “I was going to end up pumping gas somewhere.”

“I sat out on that old LST,” Kramer told Phelan, “and I did some serious thinking. No more gambling, no more staying up late, no drinking…I decided to go all out for a few major tournaments in 1946. It worked out like a dream.”

Advertising

Kramer won titles at Wimbledon and Forest Hills immediately after the war. In 1948, he turned pro and was guaranteed $50,000 for a tour with Riggs. By then he was ready for the big leagues. He won the tour, 69 matches to 20, and became the top professional. He continued in tennis as a player, promoter, tournament director, broadcaster—and eventual bête noire of Billie Jean King—for the next 40 years. His signature Wilson racquets were among the most popular in the game’s history. He never had to pump gas.

After the war, he and Gloria had five sons. One of them, Bob, continued his father’s legacy as an L.A.-area tournament director, and also served as a Navy pilot. A few years ago, Bob joined his family in dedicating a plaque at the Mount Soledad Veterans Memorial in La Jolla, Calif., commemorating Jack’s war service. On the plaque (pictured below) is a brief history of his Pacific landings, and the medals he won.

A Tale of Two Soldiers, and Tennis Players: Jack Kramer and Joe Hunt

Advertising

This history, and these honors, weren’t news to Bob, exactly, but they also weren’t things that his father had often brought up or lingered over.

“You know those greatest generation guys,” Bob Kramer says. “They didn’t like to talk about the war. I think they were happy it was over.”

Joe Hunt, it seemed, wanted to do as much he could before the conflict came to an end.

As a college student, he had left the sunny sporting life of Southern California to sign up at the Naval Academy and throw himself into the country’s upcoming war effort. Once he graduated, Hunt was sent back to California, where he spent two years on a destroyer, the USS Rathburne, in San Diego and the Pacific. After being granted leave to play at Forest Hills in 1943, he was sent in the other direction, to serve in the Atlantic. Still, it wasn’t enough.

“Joe got the bug to be a flier,” his friend and New York Times reporter Allison Danzig wrote. “Some tried to discourage him, but he made up his mind. It wasn’t alone the glamour and thrill of being a fighter pilot that appealed to him. Aviation, he decided, was to be the next big thing in the future and he wanted in on it.”

In late 1943, Hunt applied for a transfer to the Navy Air Force, and, with his wife, Jacque (who was also a very good tennis player), traveled first to a training center in Dallas, and then to a base in Pensacola, Fla. There he met up with fellow player and pilot Ted Schroeder, who had won at Forest Hills in 1942. Unable to secure leave for the 1944 U.S. Nationals, Hunt and Schroeder staged their own, two-man U.S. championships at the Bayview Park Center in Pensacola that year. A huge crowd came out to see the last two Forest Hills winners take each other on. Hunt would beat Schroeder in what would be the last tennis match of his life.

Soon after, Hunt was transferred to Daytona for flight training. It was there that on February 2, 1945, he went up to 10,000 feet in a Grumman Hellcat fighter plane for a target run. Normally, the pilot would dive to 4,000 feet and then pull out, and that’s what Hunt’s instructors told him to do over the plane’s radio. But the aircraft went into a spin instead, and ended up in the ocean. By the time rescue boats reached the crash spot, it had sunk. Only pieces of it would be found.

“Nobody really knows what happened,” Joseph Hunt says. “It was determined that there was no pilot error, but there could have been something wrong with the plane, or the life raft may have inflated accidentally. He could have blacked out from the G force.”

Two weeks shy of his 26th birthday, Hunt was dead. American Lawn Tennis Magazine put a photo of Hunt in his plane on its next cover, and Danzig paid tribute in the New York Times.

“Fame did not go to his head. He was serious in his outlook, but did not take himself or his position in tennis that way….He did the right and fair thing instinctively.”

“Joe was every inch the ideal of what every parent would like his son to be,” Danzig concluded. “He was fine all the way through. Tennis isn’t going to be the same without him.”

Hunt’s training class would graduate in July 1945. As the young pilots waited to be called up and given their assignments, the U.S. dropped atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki and essentially ended the war.

“He may never have had to go,” Joseph Hunt says.

Advertising

Kramer and Hunt believed their 1943 final at Forest Hills was just the beginning for them. Surely they would vie for more major titles, and team up to bring the Davis Cup home. Surely, they would put on finer performances than this match between a man with food poisoning and another with a cramp. As it was, it would be their last meeting. But while it wasn’t the greatest final in Forest Hills history, it had one of the most memorable conclusions.

Serving at 0-5, 15-40 in the fourth set, Kramer hit a mid-court forehand and moved toward the net. Before he made it there, though, his approach shot landed long, and the match was over. Rather than lifting his arms in celebration, Hunt, who had been nursing a leg cramp for the better of the fourth set, collapsed and couldn’t get up. Kramer walked across the court to make sure his friend was OK.

“There I was, the loser, standing up dead on my feet while he was the winner, fallen in a heap,” Kramer said. “If I’d kept that ball in the court, I think I would have been the champ by default.”

Instead, Kramer sat down on the grass and, one soldier-player to another, shook Hunt’s hand in congratulation.

A Tale of Two Soldiers, and Tennis Players: Jack Kramer and Joe Hunt

Advertising

Kramer and Hunt, just after their match at Forest Hills. (International Tennis Hall of Fame)

Three decades later, in the early 1970s, a young Joseph Hunt—Joe’s grand-nephew and namesake—attended the Pacific Southwest Championships, the tournament that Kramer ran at the Los Angeles Tennis Club.

“I saw Jack there, and somebody in my family said, ‘You have to go meet him,’” Hunt says. “So I introduced myself, and he said, ‘Are you related to THE Joe Hunt?’ He invited me over to sit with him and talk. He said, ‘When Joe died, I lost my greatest rival.’”

“Jack talked about how he and Joe had been Davis Cup partners, but you know what he never mentioned?” Hunt continues with a laugh. “Their Forest Hills match.”

“I think Jack still wanted that last forehand back.”