Australian Open

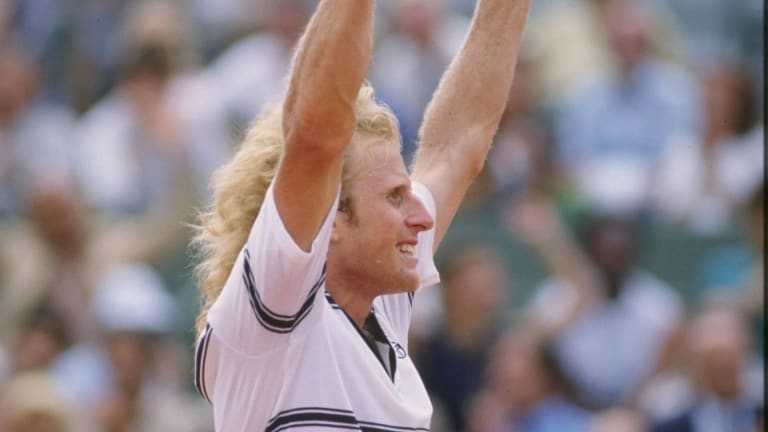

TBT, 1977: One small edge helps Vitas Gerulaitis win only major title

By Dec 31, 2020Australian Open

Australia at Last: Reflections on a first trip to the AO

By Jan 29, 2025Australian Open

Alexander Zverev must elevate his game when it most counts—and keep it there

By Jan 27, 2025Australian Open

Jannik Sinner draws Novak Djokovic comparisons from Alexander Zverev after Australian Open final

By Jan 26, 2025Australian Open

Alexander Zverev left to say "I'm just not good enough" as Jannik Sinner retains Australian Open title

By Jan 26, 2025Australian Open

Jannik Sinner is now 3-0 in Grand Slam finals after winning second Australian Open title

By Jan 26, 2025Australian Open

Taylor Townsend and Katerina Siniakova win second women's doubles major together at the Australian Open

By Jan 26, 2025Australian Open

Madison Keys wins her first Grand Slam title at Australian Open by caring a little bit less

By Jan 25, 2025Australian Open

Henry Patten, Harri Heliovaara shrug off contentious first set to win Australian Open doubles title

By Jan 25, 2025Australian Open

Aryna Sabalenka takes a rare loss in Australian Open slugfest

By Jan 25, 2025TBT, 1977: One small edge helps Vitas Gerulaitis win only major title

These were the years when the Australian Open field was rather shallow, and the 23-year-old American was the top seed.

Published Dec 31, 2020

Advertising

TBT, 1977: One small edge helps Vitas Gerulaitis win only major title

Advertising

TBT, 1977: One small edge helps Vitas Gerulaitis win only major title